Rebound in Confidence: American Democracy and the 2022 Midterm Elections

Bright Line Watch November 2022 surveys

The November 2022 midterm elections narrowly returned the United States to divided government. From the perspective of American democracy, the most noteworthy result was the underperformance of election denier candidates allied with former President Trump and their acceptance of the results (with only one prominent exception – Kari Lake in Arizona).

To understand the outcome of the election and its effects on perceptions of democracy in the United States, we fielded parallel surveys of 707 political scientists and a representative sample of 2750 Americans from November 22-December 2, 2022. These data were collected after it became clear which party would control the House and Senate1 but while votes were still being counted in most states and with some House contests still unresolved. This timing was chosen to allow us to compare the post-election results with our pre-election survey, which was conducted October 5–14, 2022. (81% of public respondents from that survey took this one as well, allowing us to see how views changed over time for those individuals.)

Our key findings are the following:

-

Public confidence that votes were counted accurately at the local, state, and national levels increased after the election and beliefs in voter and election fraud decreased. The changes were generally largest among Republicans.

-

Our expert respondents, the public overall, and Democratic and Republican partisans alike all rate the overall performance of American democracy as having improved after the election.

-

Experts and the public also view the prospects of US democracy in the future more favorably, though improvements in public perceptions were concentrated among Democrats. Partisans from both sides expect the quality of democracy to decline if the other side wins in 2024.

-

Experts regard the prospect of Donald Trump capturing the GOP nomination again in 2024 as a profound threat to American democracy and expect major declines in the quality of American democracy if Donald Trump wins. A plurality of the public shares this view. Smaller shares of both groups see Ron DeSantis as a threat and expectations of democratic decline if he wins are smaller as well.

-

A majority of experts see the Democratic strategy of supporting election deniers in GOP primaries as a threat to democracy.

-

A substantial fraction of Americans say protecting democracy is the most important consideration in which candidate they will support for president in 2024. Among partisans, more prioritized selection of a candidate who would protect American democracy over a candidate who best matched their policy preferences or one who would be most likely to win the general election.

-

In sharp contrast with previous surveys, experts evaluated major events before and after the midterm elections as predominantly conforming with traditional democratic norms.

-

Between October and November, both experts and the public perceived democratic improvement in Brazil and a decline in democracy’s prospects in China.

Confidence in American elections

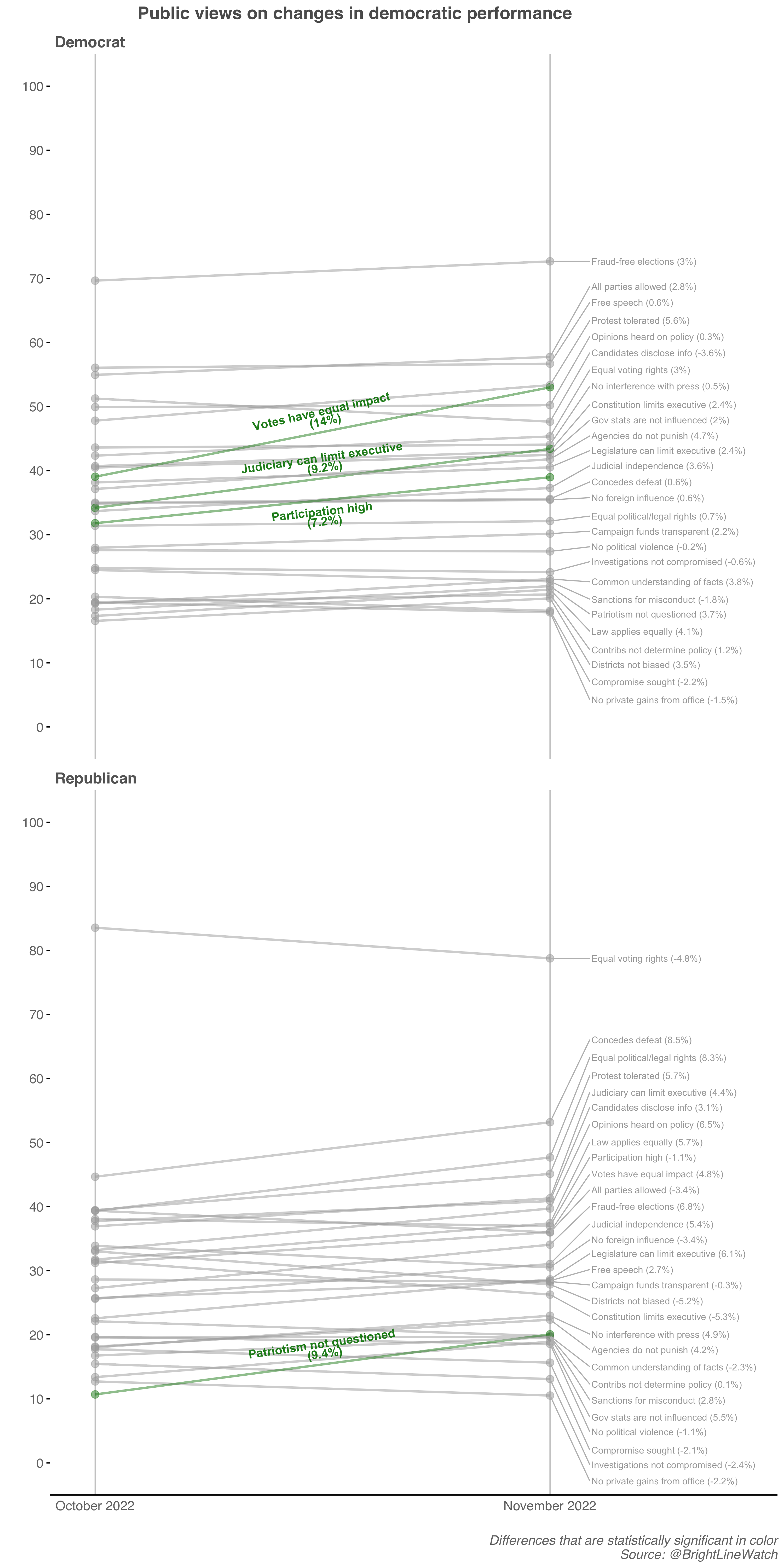

We asked respondents to report their confidence that their own vote, votes in their state, and votes nationwide in the November 2022 midterm elections were counted as voters intended. We prospectively asked the same battery of questions in October, allowing us to analyze change over time in the levels of “very” and “somewhat confident” responses (as opposed to “not very” and “not at all confident”) by party. These findings are presented in the figure below.

As the figure illustrates, public confidence in the integrity of vote counts rose for Democrats and Republicans for both people’s own vote2 as well as at the state level. The partisan gap in confidence in the national-level vote count widened, however. Confidence among Democrats, already high, increased from 95% to 97% for the personal vote, 89% to 92% at the state level and from 80% to 90% nationwide. Republican confidence also increased significantly from 68% to 78% for the personal vote and from 67% to 73% for the statewide vote. However, confidence in the national vote among Republicans, which was already much lower than for Democrats, did not change significantly (49% in October, 51% in November).3

We also asked respondents before and after the election about their confidence that everyone who was legally entitled to vote and sought to do so was able to cast a ballot. Among Democrats, confidence increased from 68% before the election to 77% afterward. By contrast, Republican confidence in voter access did not change appreciably (72% in October, 71% in November).

The nationwide increase in Democratic confidence in the vote count and voter access is perhaps consistent with a winner’s effect given how their party outperformed expectations in the midterms and the positive messages they are likely to have heard from co-partisans about the performance of the electoral system. Notably, however, we do not observe a decrease in Republican confidence like we found among Trump approvers after the 2020 election. In that case, confidence in voting at the national level collapsed, falling from 56% to just 28% among Trump supporters. The lack of prominent allegations of widespread fraud after the 2022 midterms, in contrast with 2020, likely explains the different pattern.

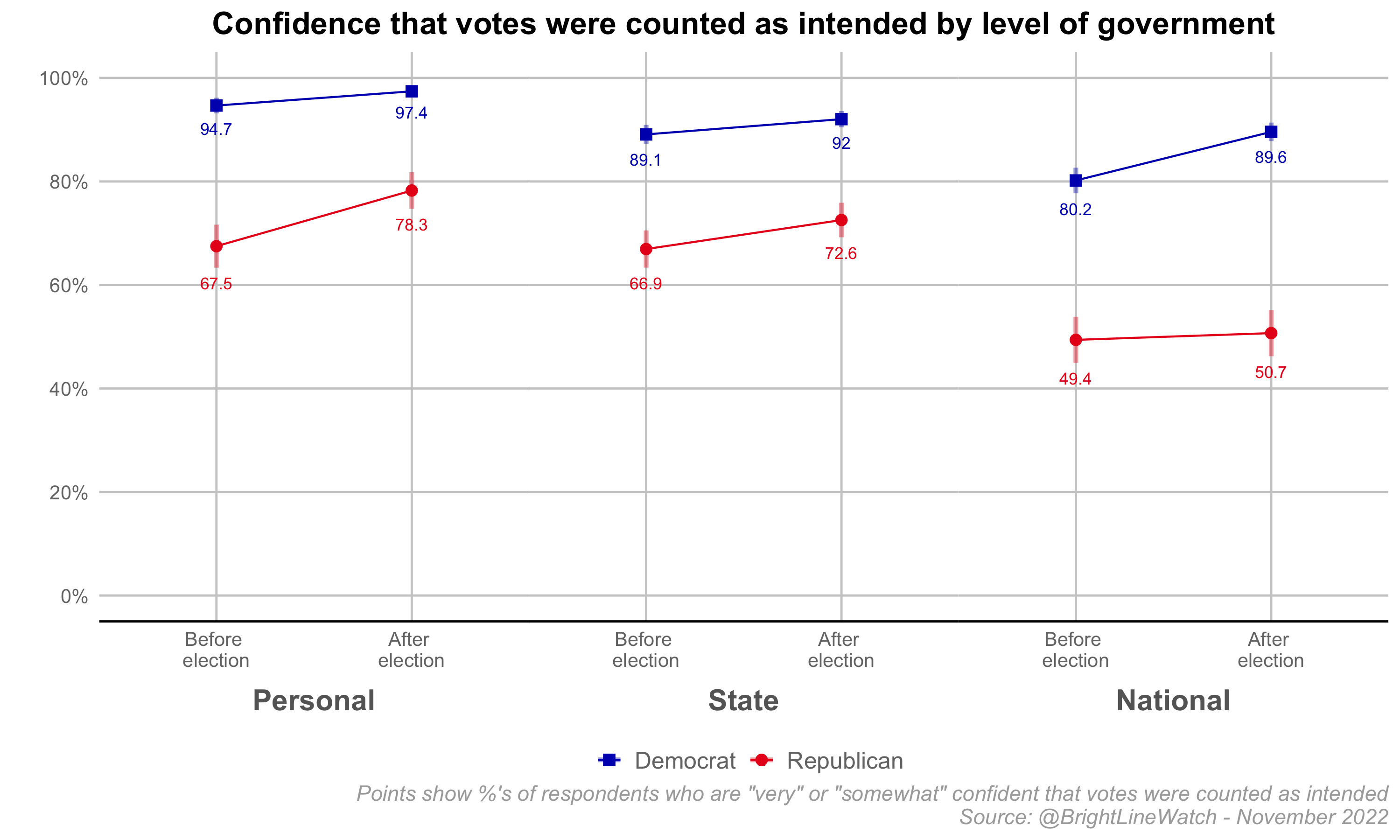

Though such allegations were rare, the most prominent attacks on election legitimacy focused on delays in counting ballots and on scenarios in which a candidate with a narrow initial lead might fall behind when more ballots were counted. We therefore included an experiment in the November survey to test whether long counts and lead changes harmed public confidence in election results. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions describing the outcome of the election for U.S. Senate in Nevada:

Election outcome baseline: Nevada’s incumbent Democratic senator Catherine Cortez Masto narrowly defeated Republican challenger Adam Laxalt.

Long count: After days of mail-in ballot counting, Nevada’s incumbent Democratic senator Catherine Cortez Masto narrowly defeated Republican challenger Adam Laxalt.

Long count and outcome reversal: After days of mail-in ballot counting and despite trailing until the last day of the count, Nevada’s incumbent Democratic senator Catherine Cortez Masto narrowly defeated Republican challenger Adam Laxalt.

Participants in each condition were then asked how confident they were that votes in the state of Nevada were counted as voters intended. We expected that reminders of the long counting process would diminish public confidence in the outcome and that a reversal in the lead at the end of that count would damage it further.

The next figure shows the percentage of respondents who said they were “very” or “somewhat confident” (as opposed to “not too” or “not at all confident”) in the integrity of the Nevada count for each partisan group by each experimental condition.

The effects we measure are in the expected direction but fall short of statistical significance. Among Democrats, whose candidate won the race, more than nine in ten respondents express confidence in the vote count regardless of the details provided (94% for both the baseline and the long count conditions and 92% among participants informed about both the long count and the lead change). Among Republicans, confidence is just 45% in the baseline condition and falls in the long count condition to 44% and to 39% in the condition with a delayed count and a late change in the leading candidate.

Beliefs in voter and election fraud

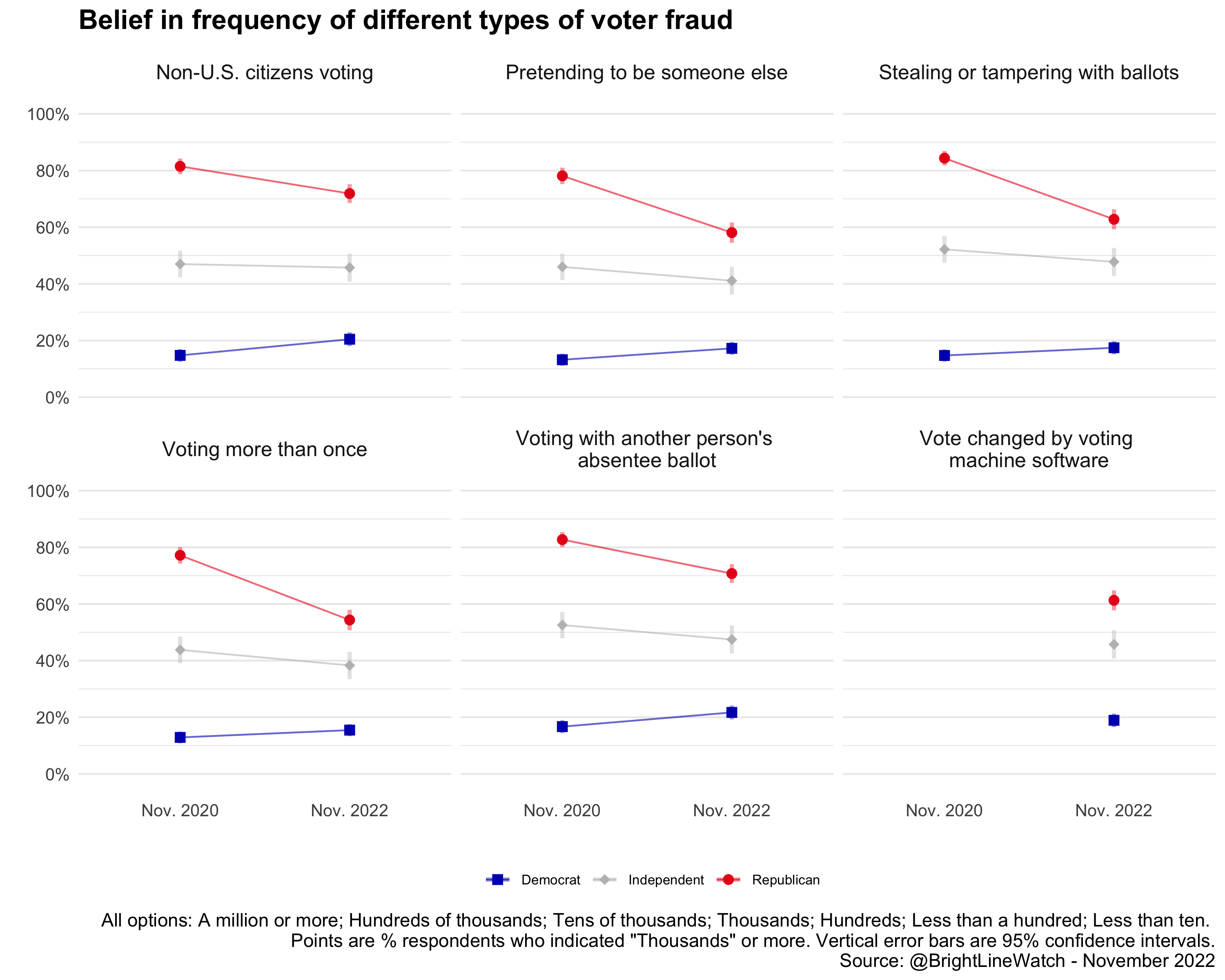

We asked respondents about the prevalence of five different forms of voter and election fraud: voting by non-citizens, voting under a false identity, stealing or tampering with ballots, voting more than once, and voting with another person’s absentee ballot. For each type of fraud, respondents were asked how many instances they believe occurred on a seven-point scale from “Less than ten” to “A million or more.” The figure below compares public beliefs in the prevalence of fraud in the 2022 election from our November survey with belief in the prevalence of fraud in the 2020 election from our poll conducted in November of that year. For each election, the figure shows the percentages of Democrats, Republicans, and independents (excluding people who lean toward one party) who estimated that “Thousands” of votes or more were affected for each type of fraud.

The most notable change is decline in beliefs in widespread fraud among Republicans. Belief that thousands or more votes were affected by non-citizens voting and absentee ballot fraud dropped by more than 10 percentage points between November 2020 and November 2022. Corresponding beliefs in thousands of cases of voter impersonation fraud, stealing or tampering with ballots, and voting more than once fell by more than 20 percentage points. (Sixty percent of Republicans believe that thousands of votes or more were changed by voting machine software manipulation, a question we asked for the first time in the November 2022 survey.)

Notably, there is no credible evidence of “thousands” of cases of any of these types of fraud – scholars find its incidence to be vanishingly rare in general, including in the 2020 election. In this sense, even millions of Democrats express beliefs in fraud that are out of line with empirical evidence. But trends in the prevalence of these beliefs are encouraging.

Conceding defeat

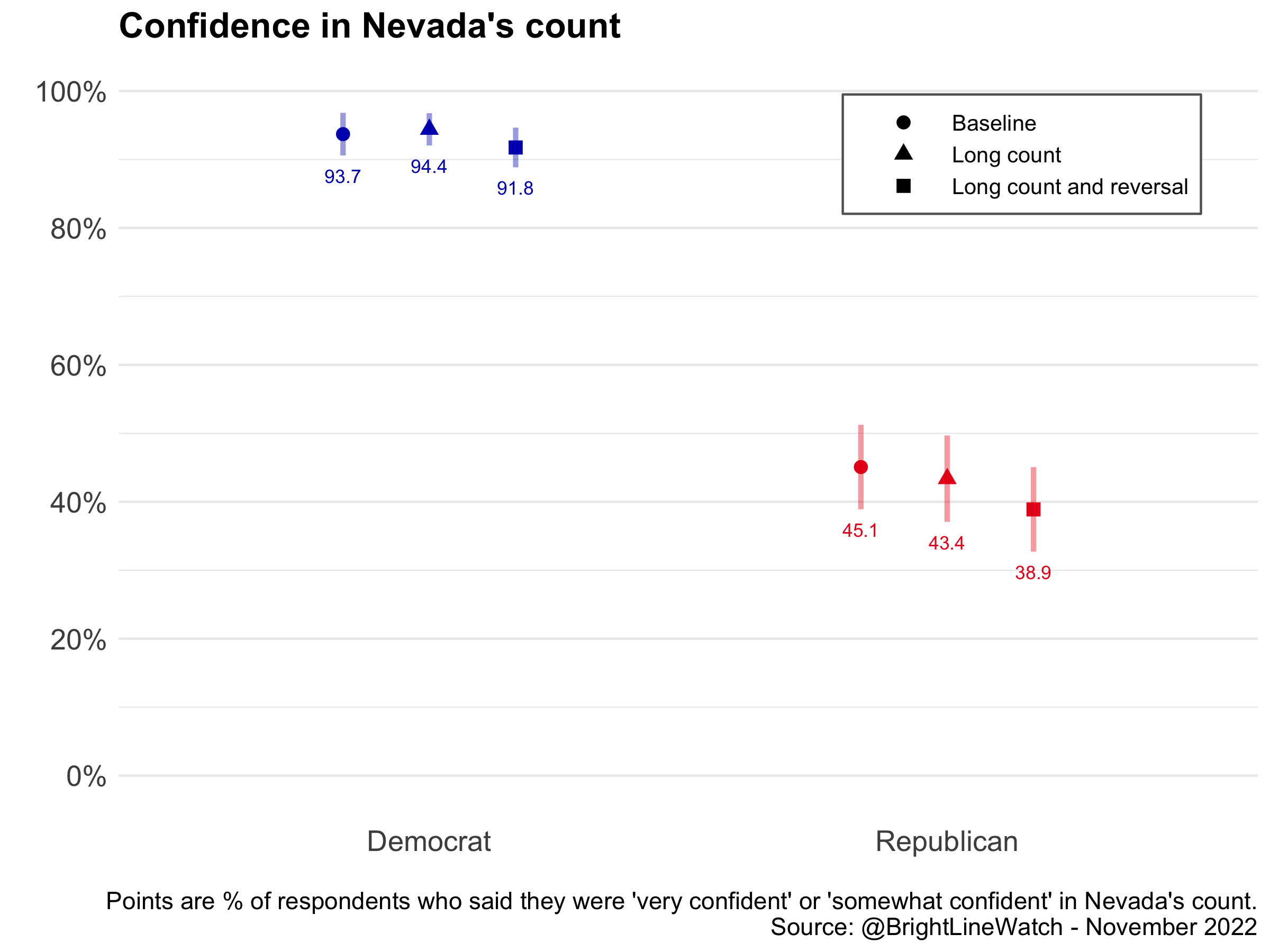

In both the October and November 2022 surveys, we asked our public sample to say how important they think it is “for a losing candidate to publicly acknowledge the winner as the legitimate representative of the state or district.” The figure below breaks out responses by partisan group for both survey waves among the random subset of respondents who were given no other information about concessions (i.e., controls in the experiment described below).

Democrats are virtually unanimous in their support for the concession norm — more than 9 in 10 said losing candidates conceding is “very” or “somewhat important” in both the pre- and post-election surveys. Prior to the election, 79% of Republicans agreed with that view, an encouragingly narrow partisan gap given what happened in the aftermath of the 2020 election. However, support among GOP identifiers declined after the election to 68%. Endorsing concessions after your party is widely seen as performing poorly in an election may be more difficult than doing so before an election in which the party is expected to do well.

To further probe attitudes toward concessions, the November survey included an experiment assessing how messages from losing Republican candidates who previously questioned the integrity of the 2020 election affect public beliefs about whether politicians should acknowledge defeat. Participants in our public sample were randomly assigned to one of four conditions:

-> a pure control, with no information provided;

-> an informational baseline with information about gubernatorial races in two states:

Doug Mastriano, the Republican candidate for Pennsylvania governor, and Kari Lake, the Republican candidate for Arizona governor, both lost to their Democratic opponents.

-> a concession condition in which respondents were provided with the informational baseline and then told that a leading election denier who lost his race had conceded:

Following the election, Doug Mastriano acknowledged defeat, saying: “Difficult to accept as the results are, there is no right course but to concede.”

-> a non-concession condition in which respondents were provided with the informational baseline and then told that a leading election denier who lost her race had not conceded:

Following the election, Kari Lake refused to acknowledge defeat, saying: “Arizonians know BS when they see it.”

Participants in the last three conditions (that is, all except the pure control group) were asked whether the specific candidates mentioned “should publicly acknowledge [his/her] opponent as the legitimate governor of [Pennsylvania/Arizona]?” We expected that receiving information about Mastriano’s concession should increase support for concessions whereas receiving information about Lake’s non-concession should have an opposite effect and that these effects should be more pronounced among Republicans than Democrats.

The figure below shows the percentage of respondents in each party who stated they “strongly” or “somewhat agree” that Lake and Mastriano should concede depending on the message that they were shown. We compare respondents in the three experimental conditions, omitting the control group analyzed above.

Contrary to our expectations, we find no evidence that these messages influenced public support for concessions. As expected, Democrats were more likely to support concessions by the defeated Republican candidate, but the messages from Lake and Mastriano had no measurable effect on their views. Republicans were somewhat less likely to say Mastriano should concede when told about Lake’s non-concession (57% versus 61%) and somewhat more likely to say Lake should concede if told about Mastriano’s concession (54% versus 49%), but none of these effects reached statistical significance.

Democratic performance

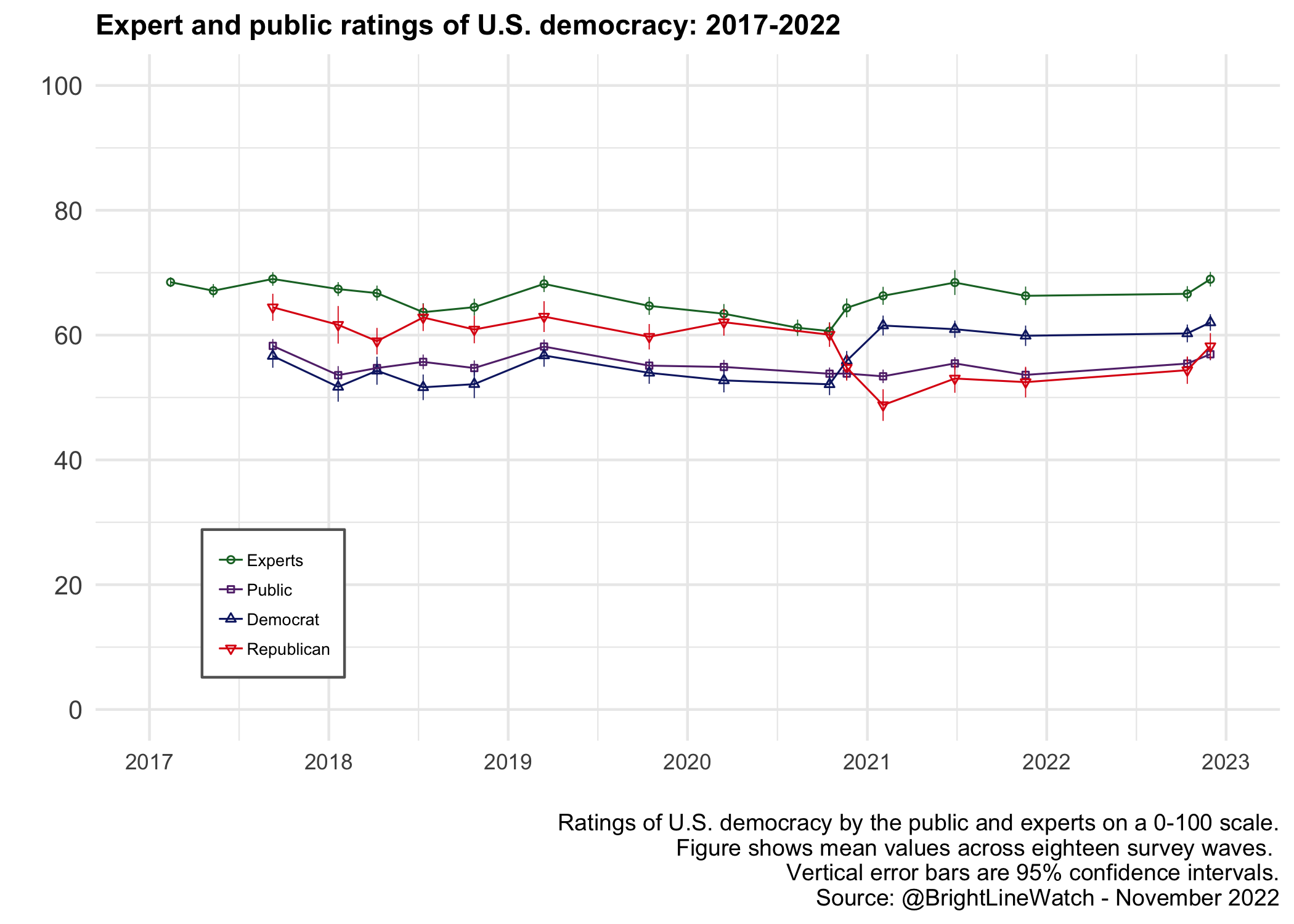

As in previous surveys, we asked expert and public respondents to rate the overall performance of American democracy on a scale from 0 to 100. The figure below reports the average ratings for experts, for the American public as a whole, and for Democrats and Republicans.

Notably, ratings of U.S. democracy increased among experts, the public overall, and both Democrats and Republicans in the public sample after the midterm election compared to before. This joint increase contrasts sharply with what happened after the 2020 election, when democracy ratings among Republicans fell sharply and ratings increased correspondingly among Democrats, leaving the overall public rating unchanged. (Expert ratings also increased.) The 2020 election pattern reflects a variant of a so-called winner’s effect in which supporters of a winning party express increased satisfaction with democracy and satisfaction among losing partisans declines. The shared increase in ratings of democracy after 2022 might reflect the ambiguous nature of a midterm in which Republicans regained control of the House of Representatives but Democrats surpassed expectations in keeping the Senate.

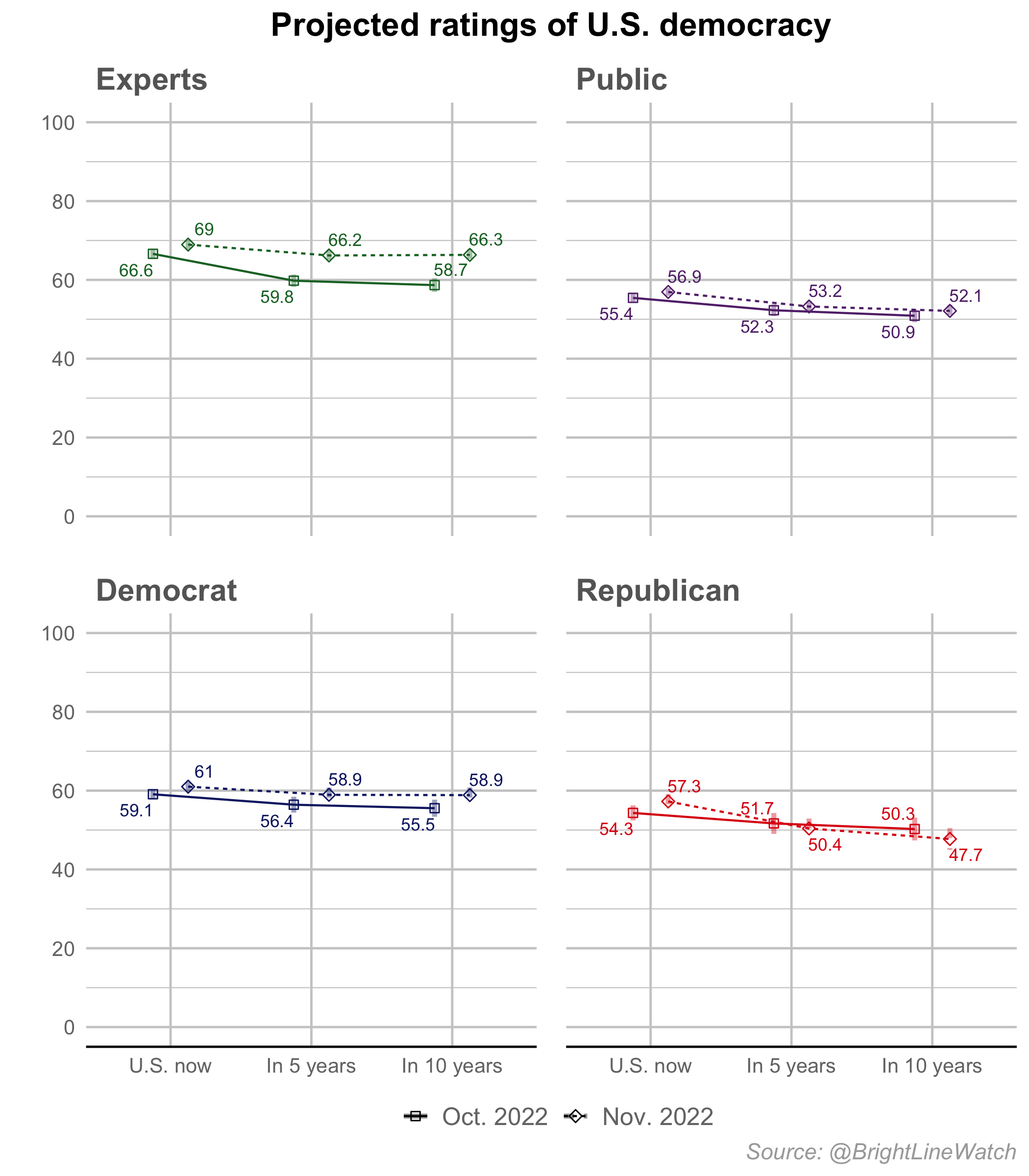

In both our October and November surveys, we also asked respondents to forecast the expected performance of American democracy in five years and in ten years on the same 0–100 scale. The next figure shows, for each partisan group and for the academic expert respondents, average five- and ten-year projections from before and after the November midterm election.

The experts, who have been consistently more positive than the public about the status of American democracy, are distinctly more optimistic after the midterm elections. Their current assessment rose from 67 to 69 and their projections shifted from a pattern of decline (60 and 59 in 5 and 10 years, respectively) to near-stability (66 in both 5 and 10 years). The shift among the public overall is in the same direction but more modest, increasing from 55 to 57 for current American democracy, 52 to 53 for 5 years, and 51 to 52 for 10 years. Disaggregating by party identification reveals that this shift is driven mainly by Democrats (59 to 61 current, 56 to 59 for 5 years, and 56 to 59 for 10 years) whereas Republican views are slightly more optimistic now (54 to 57 current) but not for the future (decreasing from 52 to 50 for 5 years and from 50 to 47 at 10 years).

Finally, the November survey also asked expert and public participants to separately project the future state of American democracy on the same 0–100 scale assuming that either Joe Biden, Donald Trump, or Florida Governor Ron DeSantis wins the 2024 presidential election. The figure below shows how these projections vary by the outcome of the 2024 race for experts, for the public overall, and for Democrats and Republicans separately.

Experts expect American democracy to perform better in five years if Biden wins again — their average rating increases from 66 given current information to 72 if he were to be re-elected. Conversely, their ratings decrease substantially if DeSantis (58) or especially Trump (49) were to win. Among the American public as a whole, projections are unaffected by a Biden win (54 under that scenario as well as under the status quo). Projections decrease slightly if DeSantis is the 2024 winner (from 54 to 50) and still further if Trump wins (to 43). These overall shifts, however, conceal opposite and offsetting partisan effects. Democrats’ five-year projections increase to 68 under Biden but plummet to 42 under DeSantis and 31 under Trump. In contrast, Republicans projections increase to 66 under DeSantis and 65 under Trump, but fall to 39 under Biden. The polarization we observe in these expectations are a familiar and troubling reminder of the extent to which conceptions of democracy differ across America’s partisan divide.

Assessments of likelihoods and threats

We asked our expert sample to rate the probability of several events that could bear on the state of American democracy occurring in the next year or two:

-

Disputes over the debt ceiling lead to a federal government shutdown in 2023

-

Joe Biden is impeached by the House of Representatives in 2023

-

Three or more states adopt rules in 2023 requiring that all ballots in the 2024 election be hand-counted

-

Donald Trump is nominated as the Republican candidate for president in the 2024 election

-

Ron DeSantis is nominated as the Republican candidate for president in the 2024 election

-

Joe Biden is nominated as the Democratic candidate for president in the 2024 election

-

President Joe Biden’s son Hunter Biden is indicted by the end of 2023

-

Criminal charges are filed against former president Donald Trump in 2023

-

The Supreme Court rules in 2023 that race-conscious college admissions are unconstitutional

The figure below reports the median probability estimate (x) and the density of probability estimates across the available range of 0% to 100% for each scenario among our expert respondents. Items are listed in descending order of estimated median probability.

A near consensus exists that the Supreme Court will rule in 2023 against the consideration of race in college admissions, anchoring the high end of the expectations scale with a median probability estimate of 85%. In addition, experts expect that Joe Biden will probably win the Democratic nomination in 2024 (66%), that disputes over the federal debt ceiling will trigger a government shutdown in 2023 (65%), and that former President Trump will face criminal charges in 2023 (60%), though with somewhat less confidence. Experts are equally divided on whether Trump or DeSantis is the favorite, giving each a 50% chance (which by definition underrates the possibility of a third candidate capturing the nomination). Experts also gave even odds to the prospect that multiple states will require that ballots be counted by hand in 2024 (50%). Finally, the experts separately rated both the likelihood of a Hunter Biden indictment in a criminal case or a Joe Biden impeachment in the House of Representatives at 40%.

In our prior survey, we asked respondents to forecast three events related to the 2022 election. The median forecast was 75% that Republican candidates who lose elections for statewide office in two or more different states would refuse to concede defeat. As of this writing, it appears that this forecast was correct. In Arizona, the losing Republican candidates for governor, secretary of state, and attorney general are all contesting their defeats and no public evidence of a concession can be found for Jim Marchant, a candidate for Secretary of State in Nevada, and Kristina Karamo, a candidate for Secretary of State in Michigan (both have questioned the results). However, the median forecast of 72% was incorrect that the Republican Party would win a majority in the House of Representatives despite getting fewer votes. Experts were correctly more skeptical (34%) that disputes over the election results would escalate to political violence in which more than 10 people are killed nationwide, which also did not take place.

We also asked both our experts and public participants to consider a series of events, some of which have already happened and others that could materialize in the future, and to assess the impact (if any) of each on democracy in the U.S. Respondents were first asked whether the event would benefit, threaten, or not affect American democracy. Those who selected benefit or threat were then asked a followup question about the degree of either effect. The set of prior events experts were asked to consider was the following:

-

Facebook limiting sharing of the Hunter Biden laptop story before the 2020 election

-

States that lean Democratic adopting independent commissions to draw congressional districts

-

Democrats supporting election-denying candidates in Republican primaries in order to improve the chances of the Democratic candidate in the general election

-

Attorney General Merrick Garland names Jack Smith as special counsel in charge of two investigations into former president Trump

The set of prospective events experts were asked to consider was the following:

-

Donald Trump is nominated as the Republican candidate for president ahead of the 2024 elections

-

Ron DeSantis is nominated as the Republican candidate for president ahead of the 2024 elections

-

Joe Biden is nominated as the Democratic candidate for president ahead of the 2024 elections

-

Criminal charges are filed against former president Donald Trump in 2023

-

Joe Biden is impeached by the House of Representatives in 2023

-

An investigation of Hunter Biden’s financial activities by the House of Representatives

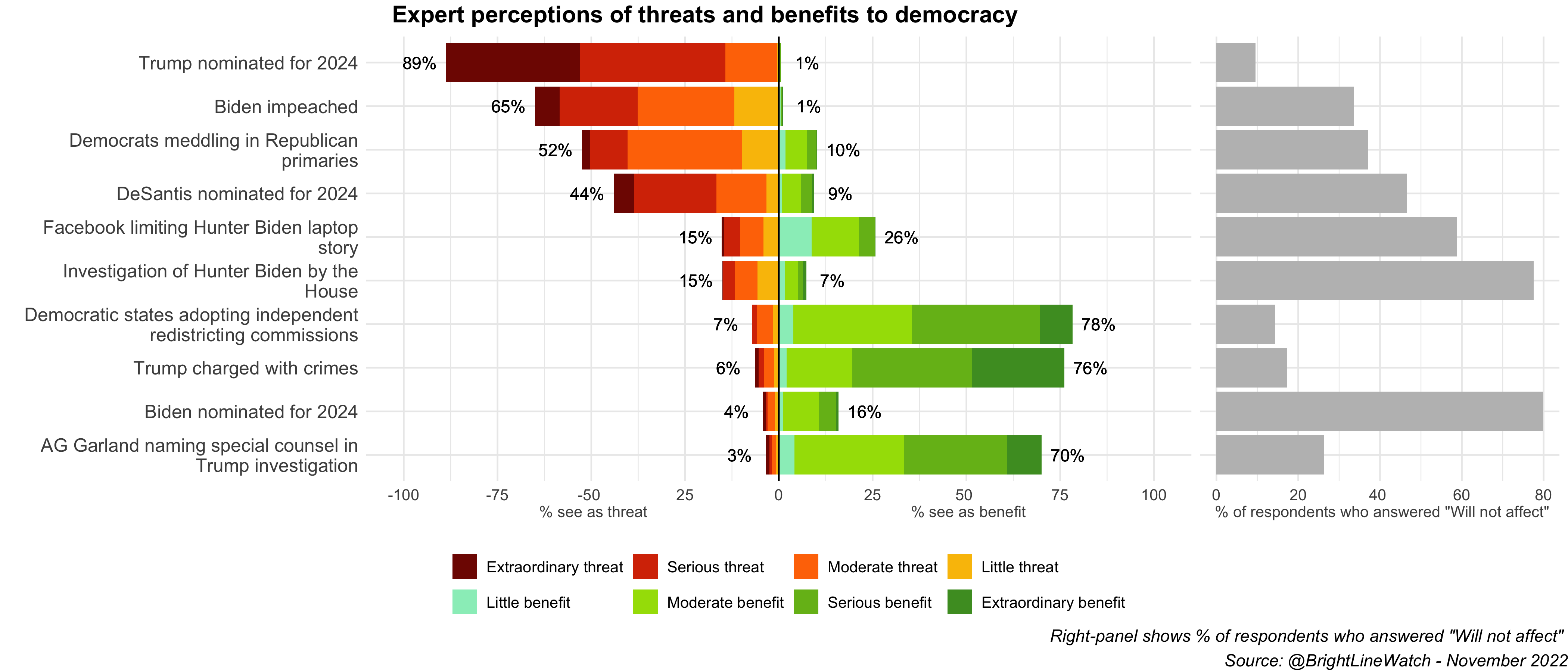

The next figure shows expert ratings of the perceived benefits and threats to democracy from these actual events or prospective events that might occur in the future. The events are presented in descending order of their overall perceived threat to democracy. (The right panel shows the percentage of respondents who rated the scenario as neither a threat nor a benefit to democracy).

Consistent with the projected democracy ratings presented above, experts overwhelmingly (89%) regard a Trump renomination for president as a threat to democracy, with 36% rating it as an extraordinary threat. A DeSantis nomination is seen as less threatening by experts — slightly more respondents (47%) perceive no impact on democracy than see it as a threat (44%). Experts also express alarm at the prospect of a Biden impeachment, which 65% see as a democratic threat.

The next most negatively rated event is one that already happened – Democrats intervening to support election deniers in Republican primaries with the hope of boosting candidates who would be easier to defeat in the general election. The strategy appeared to be successful – candidates who received Democratic backing consistently lost in the general election. However, a majority (52%) of our academic experts rate the tactic as a threat to democracy; only 10% perceive a benefit while 38% see no impact.

The middle and bottom of the figure illustrates three events the academic experts mostly regard as neither threatening nor beneficial to democracy. In October 2020, Facebook (and Twitter) limited sharing of stories about Hunter Biden’s laptop, a controversial decision that attracted widespread criticism on the right. In total, 15% of experts regard Facebook’s action on the laptop story as threatening to democracy, 26% rate it as beneficial, but a majority of 59% perceives no effect. A related item measures perceptions of planned Republican investigations of Hunter Biden’s financial activities. Fifteen percent of experts rate such an investigation as a threat to democracy, 7% as a benefit, and 78% as neither. The prospect of Joe Biden’s renomination by Democrats in 2024 is also rated as neither threatening nor beneficial by 80% of the experts.

The bottom of the figure also illustrates three events the experts regard as overwhelmingly beneficial for democracy. One is the adoption, in states controlled by Democrats, of nonpartisan commissions to draw congressional and state legislative district maps, which some partisan skeptics at the time described as “unilateral disarmament.” Experts depart from that criticism, overwhelmingly (78%) rating the commissions as beneficial to democracy. There is a similar consensus (70%) that Attorney General Garland’s decision to name a special counsel to head investigations into former president Trump is a benefit to democracy. Finally, 76% would regard criminal charges against Trump in 2023 as benefitting democracy, undaunted by skeptics’ concerns about a spiral of retribution.

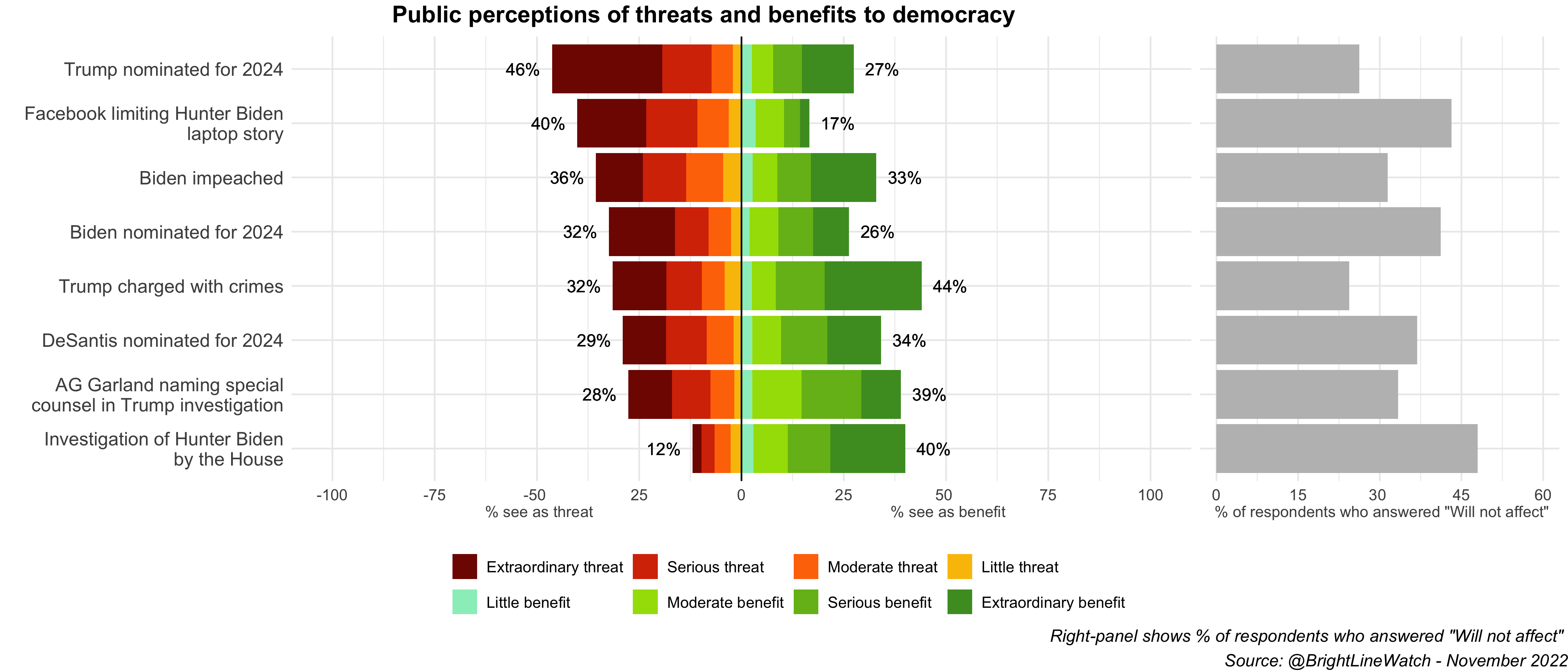

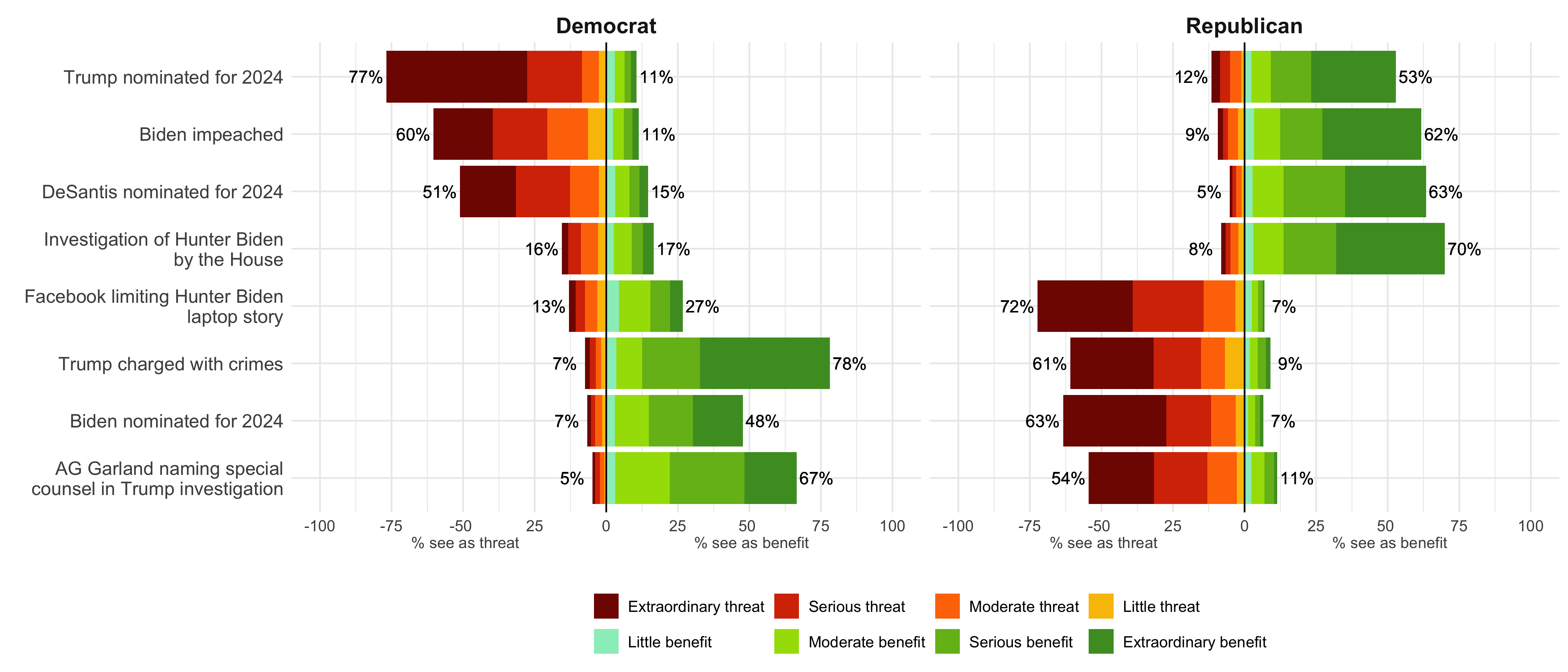

The set of events presented to our public sample was the same as to the experts except it did not include the items on independent districting commissions or Democratic Party support for election-denig candidates in Republican primaries. The figure below shows overall public responses.

A plurality of Americans (46%) regard a Trump nomination in 2024 as a threat to democracy — and most in that category regard it as an extraordinary threat. 27% would welcome Trump’s nomination as a democratic benefit and an equal number regard it as not affecting democracy. The public splits roughly in thirds on Biden and DeSantis nominations – for Biden, 32% threat, 26% benefit, 42% neither; 29%, 34%, and 37%, respectively, for DeSantis.

Many more Americans see Facebook’s 2020 treatment of the Hunter Bien laptop story as a threat (40%) than as a benefit (17%), with another 43% seeing no impact on democracy in that episode. Slightly more Americans would regard an impeachment of Joe Biden in 2023 as a threat (36%) than as a benefit (33%), with 31% anticipating no effect on democracy. More respondents see democratic benefits than threat in Merrill Garland’s appointment of a special counsel (39% to 28%) and in the prospect of a Trump prosecution (44% to 32%), and many more anticipate a benefit (40%) than a threat (12%) from an investigation of Hunter Biden.

Finally, the next figure shows responses on these items broken out by partisanship.

Consistent with other results, we observe sharp polarization. A majority of Democrats perceive a Trump nomination (77%), a Biden impeachment (60%), and a DeSantis nomination (51%) as a threat to democracy, while a majority of Republicans see these actions as benefits to democracy (53%, 62%, and 63%, respectively). Conversely, a majority of Republicans see criminal charges against Trump (61%), a Biden nomination (63%), and the DOJ special counsel investigation of Trump (54%) as threats to democracy, while approximately half of Democrats or more see these as benefits to democracy (78%, 48%, 67%, respectively).4 Finally, we consider the two items related to Hunter Biden. Republicans see a House investigation of the President’s son as a benefit to democracy (70%) and Facebook’s intervention in the laptop story as a threat (72%), whereas a majority of Democrats said these were neither a threat nor a benefit (60% and 68%, respectively).

Looking ahead to 2024

We also sought to measure the relative importance that Americans assign to protecting democracy in choosing among primary candidates in the 2024 presidential election. To do so, we asked respondents the following question, randomizing inclusion or exclusion of the option about protecting democracy:

Thinking about the [Democratic/Republican] nomination, which of these best describes who you would like to see win the [Democratic/Republican] nomination?

The candidate whose policies I most prefer

The candidate with the best chance to win in the general election

[The candidate who is most committed to protecting American democracy]

This design allows us to see the relative importance given to democracy versus policy and likelihood of winning the general election as well as how its inclusion changes the support given to the other two options — policy preference and the best chance of winning the general election. (Partisan independents were asked to express their priorities for both parties’ nominations.)

The figures below shows priorities for Democrats, Republicans, and independents with the response shares for each group shown when the protecting democracy option was excluded (light shading, dots as markers) and when it was included (diagonal hatching markers).

The top row of the figure shows that, when asked whether they prioritize electoral viability or policy compatibility for their party’s presidential nomination, both Democratic (61% to 39%) and especially Republican (74% to 26%) partisans prioritize policy compatibility. When we offer all three options, however, protecting democracy draws more support than either of the others among both Democrats (40%) and Republicans (41%). Notably, protecting democracy draws relatively more support among partisans who would otherwise have selected policy as the most important consideration (declining from 60.6% to 31.4% among Democrats and 73.4% to 40.7% among Republicans compared to much smaller declines among those who prioritized winning).

The second row of the figure presents data for partisan independents, who make up 17.6% of our public sample.5 We are particularly interested in the priority this group places on protecting democracy because independents are a pivotal voting bloc in presidential elections. We asked the independents about their priorities for nominations in both of the major parties. When given only two options, independents prioritized policy over winning even more than Democrats or Republicans did, which is consistent with their lack of concern about the fortunes of a particular party. Like the partisans, though, many independents say they prioritize candidates who would protect American democracy when offered that response option. 39% of independents make protecting democracy their top priority for a Democratic nominee (compared with 47% for policy and 14% for electoral viability), and 43% prioritize protecting democracy among Republicans (compared with 45% for policy and 12% for electoral viability).

As Americans begin to contemplate the 2024 presidential election, many at least say that protecting democracy is a top priority in which candidate they will support. Among Democratic and Republican partisans (the key players in the nomination process), more people prioritize protecting democracy (41%) than either policy compatibility (35%) or general election viability (24%) among those who were offered all three response options.6

Events

We continue to survey experts about recent events, asking them to separately rate events as normal or abnormal and as important or unimportant. The complete list of events (with the exact text shown to respondents) is provided in the report appendix; the average ratings provided by our experts are plotted on the figure below.

Our primary goal in conducting this exercise is to identify events that appear in the shaded upper-right quadrant because experts rated them as both mostly important to important and mostly abnormal to abnormal. For the first time since we began surveying on this topic, however, that region of the figure is nearly empty, including only Kari Lake’s refusal to concede in the Arizona governor’s contest. By contrast, experts rate several events in which challenges to democracy were turned back as normal and important, including widespread concessions by defeated Republicans from both the establishment and Trump-aligned wings of the party and defeats at the state level of most election deniers running for Secretary of State.

Of course, the distribution of responses depends on the events we selected. We only note that we sought to include the most relevant potential events that were salient to American democracy, including those that could be rated as important and abnormal. The shift toward normalcy in this survey is, in our experience, unusual and noteworthy.

Democracy in other countries

Our November surveys also asked respondents to use the same 100-point scale to rate democracy in five additional countries: Brazil, China, Israel, Russia, and the United Kingdom. Bright Line Watch surveys conducted in January 2018 and October 2022 measured perceptions of democracy abroad. We repeated the exercise immediately after our prior survey because important events took place between surveys that could affect evaluations of governance in each country:

-

Brazil held the second round of its presidential election on October 30. The first round of the election, on October 2, had produced a closer-than-expected contest between challenger (and former president) Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro. During our prior survey, Bolsonaro was publicly criticizing Brazil’s election administration and signaling that he would not recognize or accept the second-round outcome if he did not win. In the intervening month, da Silva narrowly defeated Bolsonaro, 51%-49%, who, after a 48-hour silence, grudgingly instructed his administration to begin an orderly transition of authority.

-

China’s Communist Party held its 20th party conference in late October, culminating with the confirmation on the 22nd that Xi Jinping will serve as party chairman for a third consecutive term. After the party conference, the centralization and personalization of authority in China appears higher than at any time since the era of Mao Zedong.

-

Israel held a parliamentary election on November 1 – its fifth in the past four years – and appears set to return Benjamin Netanyahu to the prime ministership, leading a coalition that may include greater representation than any previous government has from parties of the religious right. Netanyahu’s potential return to the chief executive role, however, is complicated by the unresolved status of legal charges against him for bribery, fraud, and breach of trust during previous terms as prime minister.

-

Russia suffered its most prominent battlefield setback since the early days of its Ukraine invasion with its retreat, in the second week of November, from the southern city of Kherson. As Ukrainian forces reoccupied the city, they discovered and publicized evidence of Russian human rights abuses during the months of its occupation.

-

The United Kingdom experienced a sudden change of government when Liz Truss resigned as prime minister on October 20 after only six weeks in the office and was replaced five days later by Rishi Sunak.

The next figure shows mean ratings by country from the expert and public samples in the November survey (left panel) and changes from October to November for each group (right panel).

As the figure shows, ratings increased the most for Brazil after Bolsonaro’s acceptance of the election results there, increasing by 10 points in the expert sample and 3 points in the public sample compared to October. We also observe small but marginally significant decreases in ratings of democracy in China among experts and among the public (by 2 and 3 points, respectively). For the other countries included, we detect no appreciable change – democracy ratings were not unmoved by Truss’s resignation in the United Kingdom, the return of Netanyahu to office in Israel, or Russia’s ongoing military travails in Ukraine.

Appendix

Bright Line Watch conducted its eighteenth survey of academic experts from November 21-December 2nd, 2022 and its fifteenth survey of the general public from November 22-December 2nd, 2022. Our public sample consisted of 2,750 participants from the YouGov panel who were selected and weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population. We also surveyed 707 political science experts across a diverse range of subfields (6.0% of solicited invitations). Our email list was constructed from the faculty list of U.S. institutions represented in the online program of the 2016 American Political Science Association conference and updated by reviewing department websites and job placement records from Ph.D. programs in the period since.

All estimates shown in the report used weights provided by YouGov. Our expert sample is unweighted because we do not collect demographic data to protect anonymity. Error bars in our graphs represent 95% confidence intervals. Data are available here.

Both the expert and public samples in Wave 18 responded to a battery of questions about democratic performance in the United States. Afterward, they were asked to evaluate the quality of American democracy overall on a 100-point scale.

How well do the following statements describe the United States as of today?

- The U.S. does not meet this standard

- The U.S. partly meets this standard

- The U.S. mostly meets this standard

- The U.S fully meets this standard

- Government officials are legally sanctioned for misconduct

- Government officials do not use public office for private gain

- Government agencies are not used to monitor, attack, or punish political opponents

- All adult citizens enjoy the same legal and political rights

- Government does not interfere with journalists or news organizations

- Government effectively prevents private actors from engaging in politically-motivated violence or intimidation

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in unpopular speech or expression

- Political competition occurs without criticism of opponents’ loyalty or patriotism

- Elections are free from foreign influence

- Parties and candidates are not barred due to their political beliefs and ideologies

- All adult citizens have equal opportunity to vote

- All votes have equal impact on election outcomes

- Elections are conducted, ballots counted, and winners determined without pervasive fraud or manipulation

- Executive authority cannot be expanded beyond constitutional limits

- The legislature is able to effectively limit executive power

- The judiciary is able to effectively limit executive power

- The elected branches respect judicial independence

- Voter participation in elections is generally high

- Information about the sources of campaign funding is available to the public

- Public policy is not determined by large campaign contributions

- Citizens can make their opinions heard in open debate about policies that are under consideration

- The geographic boundaries of electoral districts do not systematically advantage any particular political party

- Even when there are disagreements about ideology or policy, political leaders generally share a common understanding of relevant facts

- Elected officials seek compromise with political opponents

- Citizens have access to information about candidates that is relevant to how they would govern

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in peaceful protest

- Law enforcement investigations of public officials or their associates are free from political influence or interference

- Government statistics and data are produced by experts who are not influenced by political considerations

- The law is enforced equally for all persons

- Incumbent politicians who lose elections publicly concede defeat

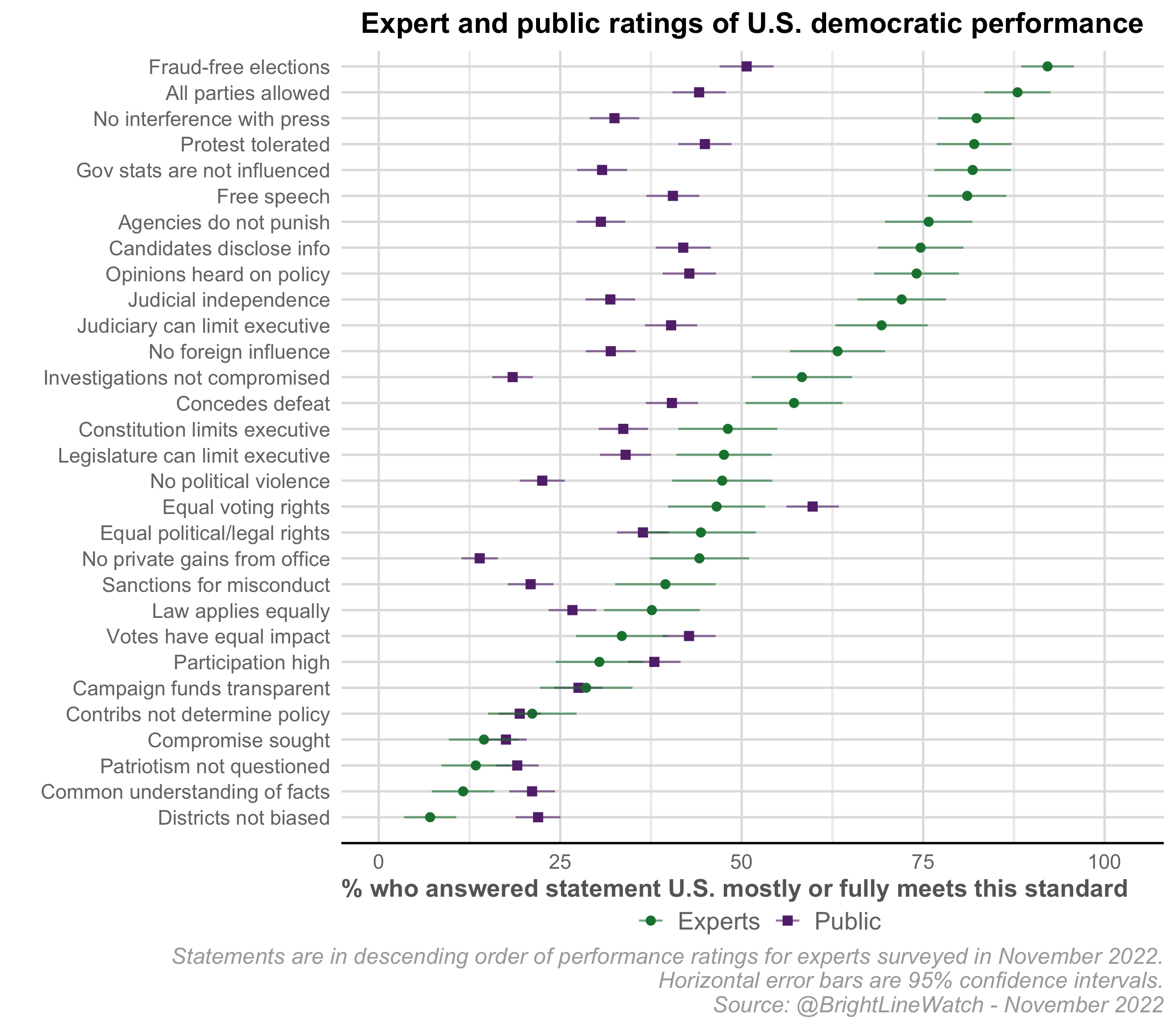

The figure below breaks out performance ratings on each of 30 democratic principles. The markers for each principle indicate the percentage of expert (green) and public (purple) respondents who regard the United States as fully or mostly meeting the standard (as opposed to meeting it partly or not at all). Consistent with the overall ratings, the experts rate U.S. democratic performance more positively than the public overall. Few exceptions exist, however, such as voting rights being equally protected for all citizens, politicians operating with a common understanding on factual matters, and electoral districts not systematically favoring one party over the other.

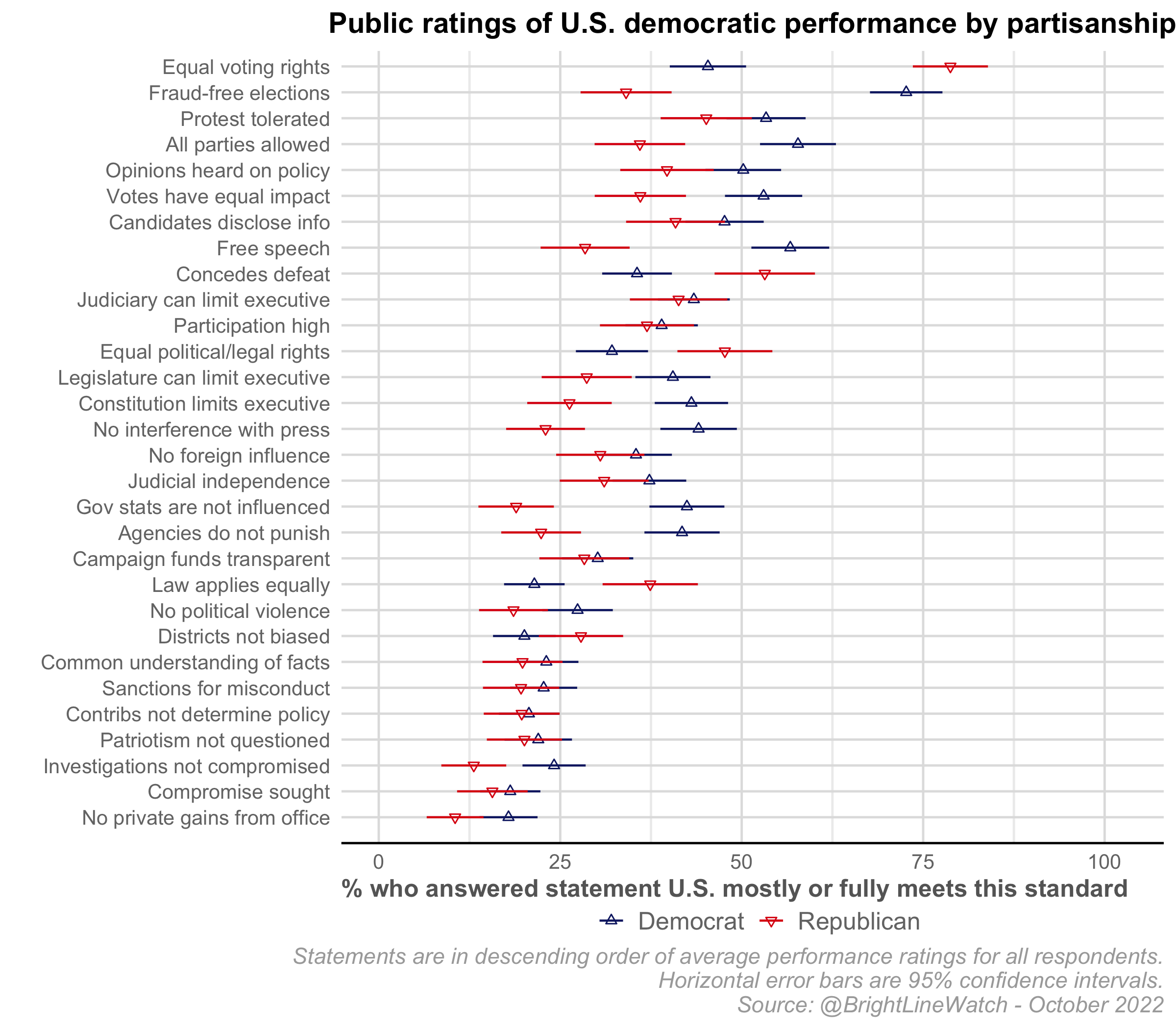

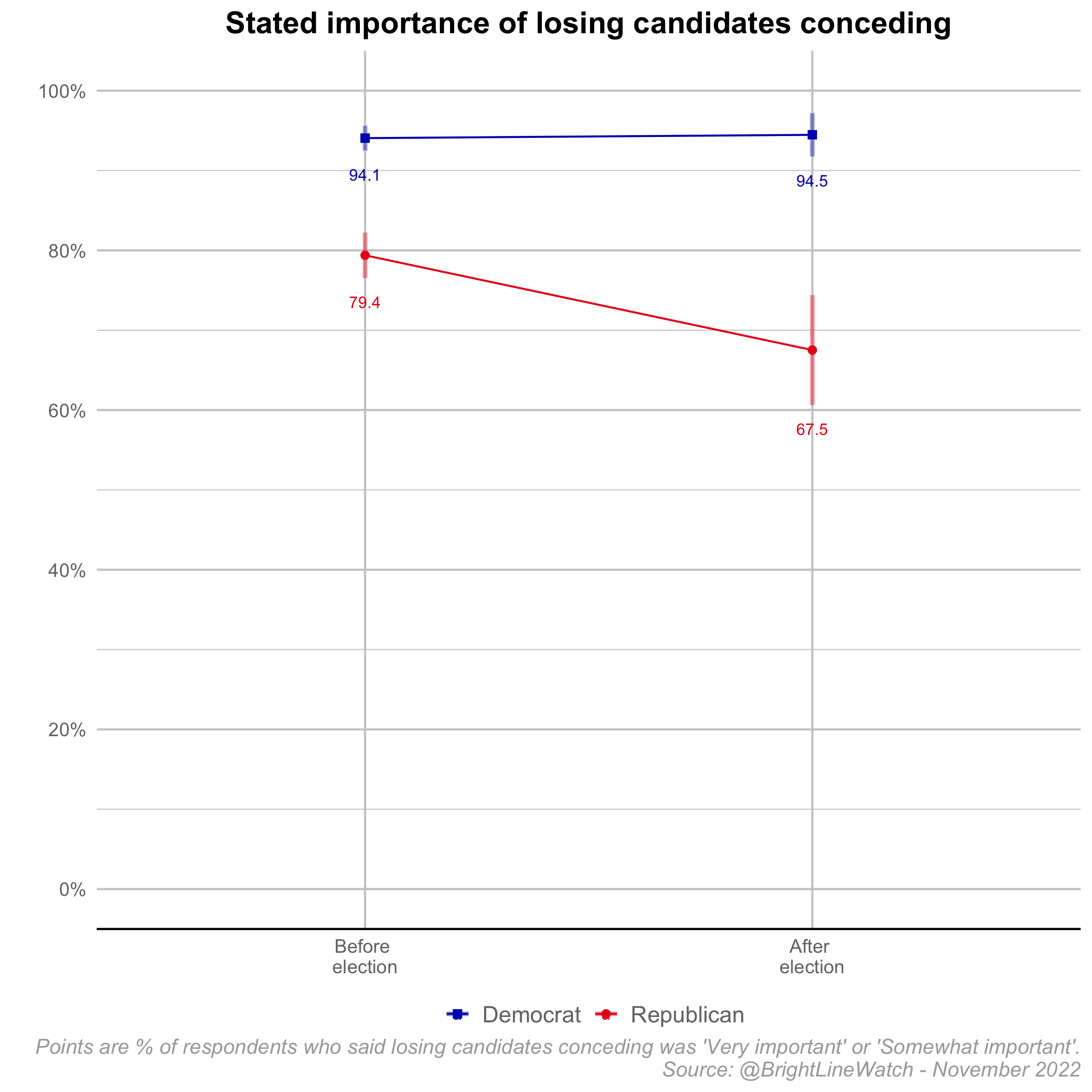

The next figure shows performance assessments on the same 30 principles for the public sample only by respondent partisanship. On some principles, middling overall public assessments hide stark partisan polarization.

The figure below plots belief that Joe Biden is the rightful winner of the 2020 election among Democrats, Republicans, and the American public as a whole since November 2020:

Additional components of expert survey

Political events

In this series of questions, we ask how normal or abnormal and how important or unimportant recent political events are.

Is this normal or abnormal?

- Normal

- Mostly normal

- Borderline normal

- Mostly abnormal

- Abnormal

Is this unimportant or important?

- Unimportant

- Mostly unimportant

- Semi-important

- Mostly important

- Important

Events list

- Republican candidates for Secretary of State who denied the results of the 2020 election lost in eight of eleven states, including the battlegrounds of Arizona, Michigan, and Nevada.

- Establishment Republican candidates who lost in the midterm elections admit defeat and concede.

- Most Trump-aligned Republican candidates who lost in the midterm elections admit defeat and concede.

- President Joe Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping meet and agree to resume bilateral climate talks.

- In the midterm elections, the Republicans retake control of the House of Representatives and win the popular vote.

- After losing the gubernatorial election in Arizona, Republican nominee Kari Lake refuses to concede.

- Former president Donald Trump lashes out at Florida governor Ron DeSantis, a potential rival for the 2024 Republican nomination.

- Former president Donald Trump announces his bid for the presidency in 2024, just one week after the midterm elections.

- Partisan control of the House of Representatives and the Senate is not clear until days after Election Day due to delays in counting ballots in multiple states.

Additional Figures

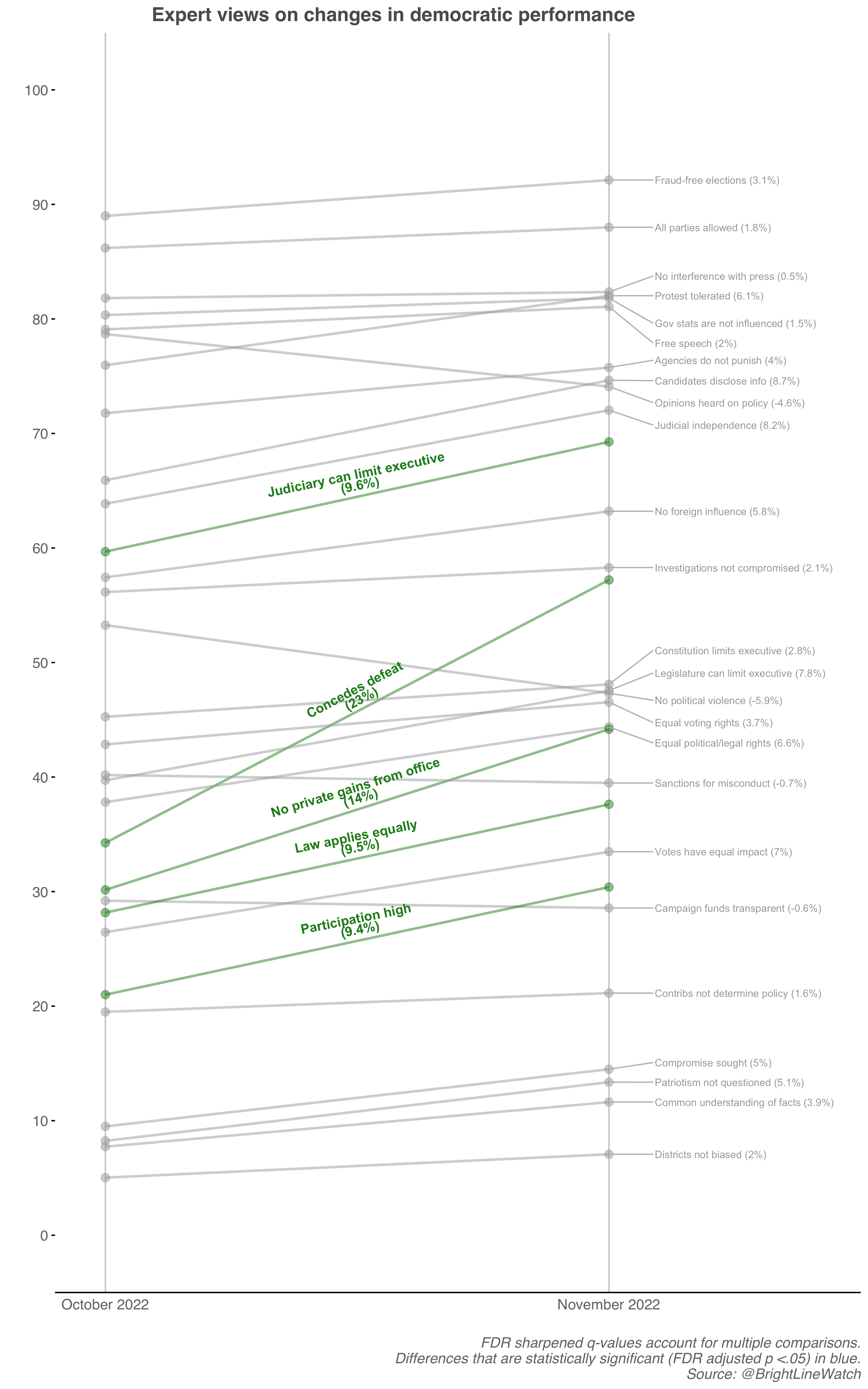

The figures below plot changes in democratic performance on specific principles since our prior survey in October 2022 for experts, the American public as a whole, and Democrats and Republicans separately.

- Democratic control of the Senate was not assured until four days after the election and the Republican House majority was confirmed eight days afterward.

- Estimates for confidence that respondents’ own vote was counted as intended are calculated among respondents who participated in both the October and November surveys and reported being “sure” that they voted in November.

- Republican recognition of Joe Biden as the rightful winner of the presidency also remained stable (33% in October, 35% in November), albeit at a higher level than in 2021 (when it was 26–27%).

- Using the counterfactual question format developed by Graham and Coppock, we also tested for changes in perceptions that law enforcement investigations of public officials or their associates are free from political influence or interference attributable to the special counsel appointment. Consistent with the polarization reported above, we estimate a significant improvement in perceived performance on this principle among Democrats (comparing performance ratings asked in the standard fashion with a counterfactual in which people are asked how they would respond if the special counsel had not been appointed) but no measurable change for Republicans.

- Following standard practice, we characterize as independents those respondents who declare no partisan affiliation and also say they do not lean toward either party. We group “leaners” with their respective parties in presenting results.

- Tallying responses across the full public sample is not straightforward because we asked partisan independents to express priorities for both the Democratic and Republican nomination. Nevertheless, given the top priority for democracy expressed by partisans, and its high priority among independents (who constitute less than one-fifth of the sample), we can say that protecting democracy is the top priority of more respondents than either other option.