American Democracy After Trump’s First Year

Bright Line Watch

February 8, 2018

In January 2018, as Donald Trump completed his first year as president, Bright Line Watch conducted its fourth expert survey on the state of U.S. democracy. At the same time, we conducted an identical public survey – our second – with a nationally representative sample of Americans. This approach allows us to assess whether experts and/or the public believe the quality of democracy has changed in the U.S. during President Trump’s tenure. We also asked respondents to rate the overall quality of democracy in a dozen other countries, including Canada, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela, allowing us to assess how experts and the public believe America stacks up against other countries. Finally, we disaggregate results from our public survey to see how changes in these perceptions vary by approval of Trump.

The overall picture is sobering. Though the public rates American democracy more negatively than our experts do (as in our previous survey), both experts and the public agree that the performance of U.S. democracy has declined. This perception of decline is mirrored for many specific democratic principles, though in some cases we observe significant divergence between Trump approvers and disapprovers.

In comparative perspective, U.S. democracy still rates reasonably high among both experts and the public, but it is not the most highly regarded democracy among either group. We also find the American public’s assessments of democracy abroad track strongly with their domestic political attitudes, particularly for some countries. Respondents who approve of President Trump rate Russia, the Philippines, Turkey, and Israel as more democratic than do Trump’s opponents, while those who disapprove of him have more favorable assessments of Canada and Mexico.

The expert survey was conducted from January 10–22, 2018. We received 1,066 responses from faculty in political science departments at universities in the United States. The public survey was fielded from January 10–18, 2018 and generated responses from a representative sample of 2,000 Americans drawn from the YouGov online survey panel.

U.S. democratic performance

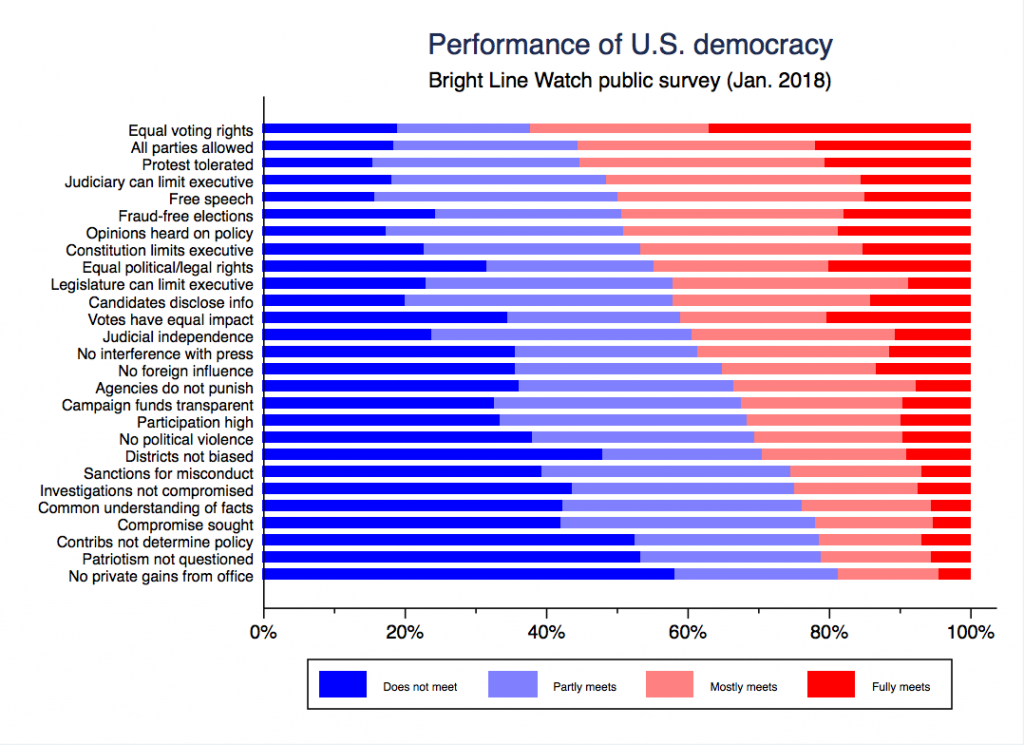

The core of the Bright Line Watch survey is a battery of 27 statements about democratic principles. Each respondent is presented with a random subset of these principles and asked to rate whether the U.S. “fully meets,” “mostly meets,” “partly meets,” or “does not meet” the standard.

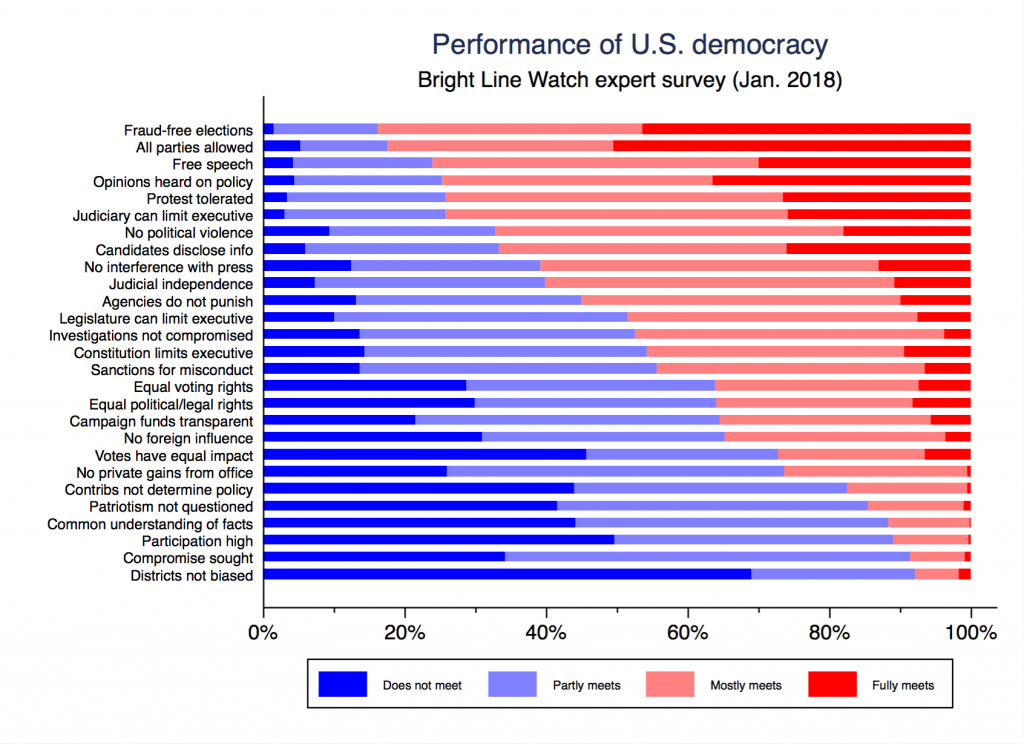

The figure below illustrates the distribution of responses on each principle among experts. The responses are listed in descending order of the percentage who regard the U.S. as fully or mostly meeting the standard. As with past survey waves, there is wide variation across principles in the share of experts who regard the U.S. as performing well. More than 80% regard U.S. elections as free of overt fraud, but fewer than 10% regard our electoral districts as unbiased or perceive our elected officials as seeking compromise with their opponents.

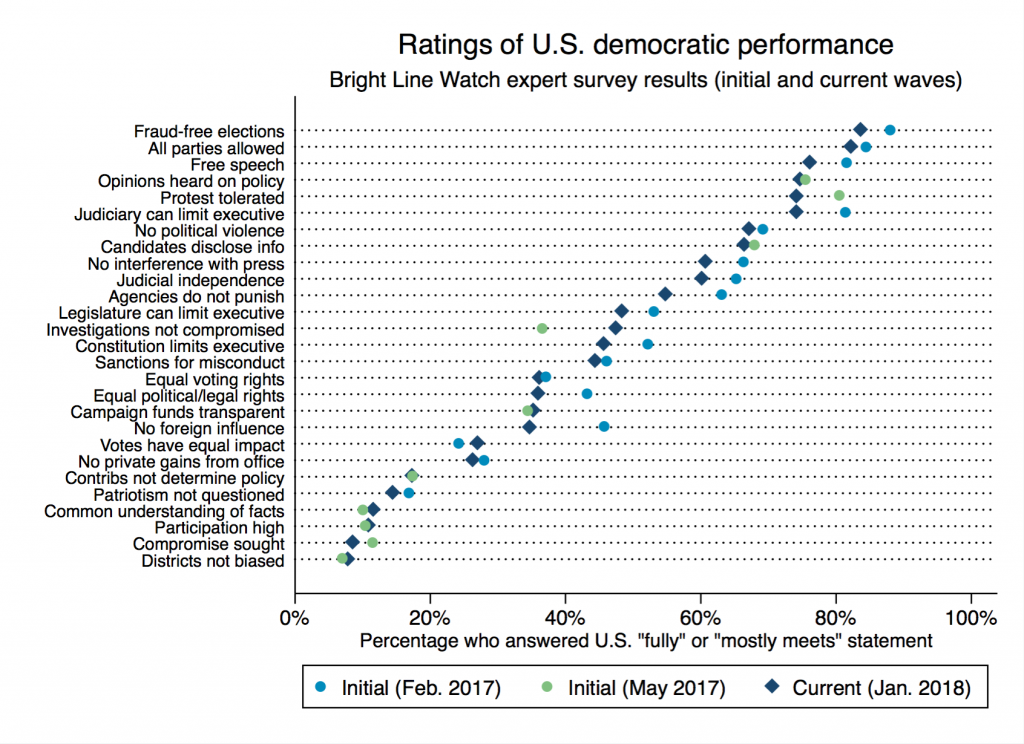

Most notably, however, we observe a broad decline in appraisals of how well American democracy is performing in both our expert and public samples. On 21 of 27 principles, the percentage of experts rating U.S. performance as high has declined over time. This pattern is illustrated in the figure below, which compares the percentage of “mostly meets” and “fully meets” responses for each principle among experts in the Wave 4 survey (dark blue diamonds) with the percentage of those responses we received when we first measured the principle in a survey.

The only principle on which respondents saw substantial improvement is the one that states, “Law enforcement investigations of public officials or their associates are free from political influence or interference.” That statement was first included in Bright Line Watch’s May 2017 survey, which took place soon after President Trump fired FBI director James Comey, prompting an exceedingly low initial rating on the principle. Evaluations increased in our Wave 3 survey, which took place after the appointment of Special Counsel Robert Mueller, before again declining somewhat to the present level. (The survival and independence of the Mueller investigation remains precarious. Just days after we concluded our Wave 4 survey, news sources revealed that President Trump attempted to fire Mueller in June 2017 and was only deterred from doing so when White House Counsel Don McGahn threatened to resign.)

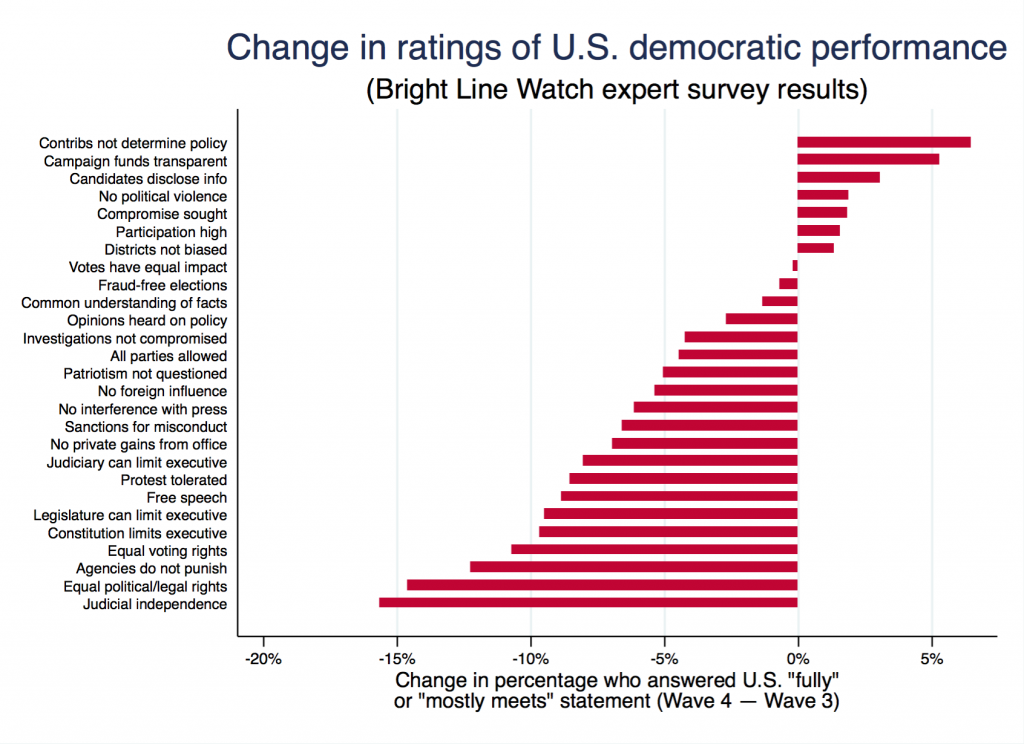

The following figure presents another way to visualize the recent erosion in perceived democratic quality, showing our principles in descending order of the change from Wave 3 to Wave 4 in “fully meets”/“mostly meets” responses. Between September 2017 and January 2018, we observe a statistically significant improvement in ratings among experts on just one principle (that campaign contributions do not determine policy). By contrast, experts perceived significant degradation on thirteen principles. The areas of greatest change are telling. All four of our principles related to institutional checks and balances experienced large declines. Expert judgment in the ability of Congress, the courts, or the Constitution to constrain the power of the executive all eroded by 8–10 percentage points, and confidence in judicial independence from the elected branches plummeted by 16 percentage points. The last four months also saw substantial declines (greater than 10 percentage points) in confidence that all citizens enjoy equal legal, political, or voting rights, and that government agencies are not used to punish political opponents.

This broad decline between our September 2017 survey and our January 2018 survey coincided with numerous revelations from the Russia investigation, including the indictments of two Trump advisors (Paul Manafort and George Papadapolous) in October; a guilty plea by Trump’s former National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn, for lying to the FBI; and confirmed reports about Donald Trump Jr.’s email exchanges with WikiLeaks during the 2016 campaign in November. During this same period, Trump has also continued to assert his right to open an investigation into Hillary Clinton; repeatedly sought to undermine the credibility of the Mueller investigation and the FBI; and attacked a circuit court ruling blocking the end of DACA on Twitter, calling the court system “broken and unfair.”

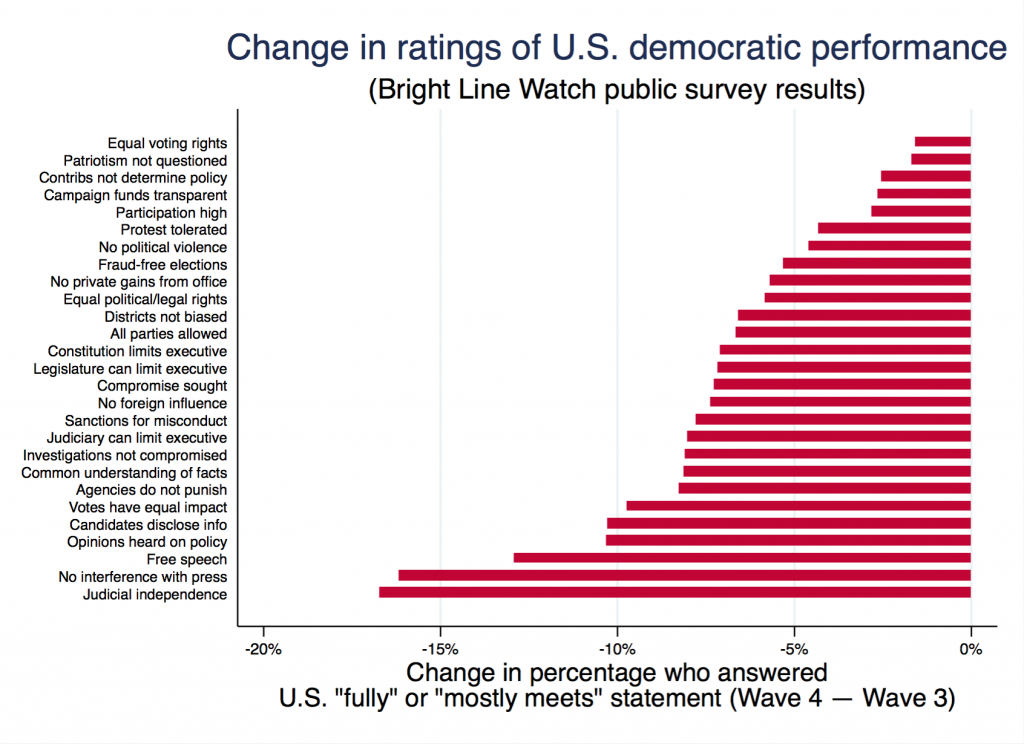

The changes we observe in public assessments of U.S. democracy over the same period were even more consistently negative than those of the experts. No statistically significant increases in performance were found, but we see statistically significant declines on 17 of 27 principles tested. Largely coinciding with our experts, assessments that the courts, the legislature, or the Constitution, can effectively check executive power dropped by 7–8 percentage points, and confidence that the elected branches respect judicial independence fell by 17 percentage points. The public results also show substantial declines (greater than 10 percentage points) in the belief that the government does not interfere with the press, protects free speech rights, that opinions on policy are heard, and that candidates disclose information.

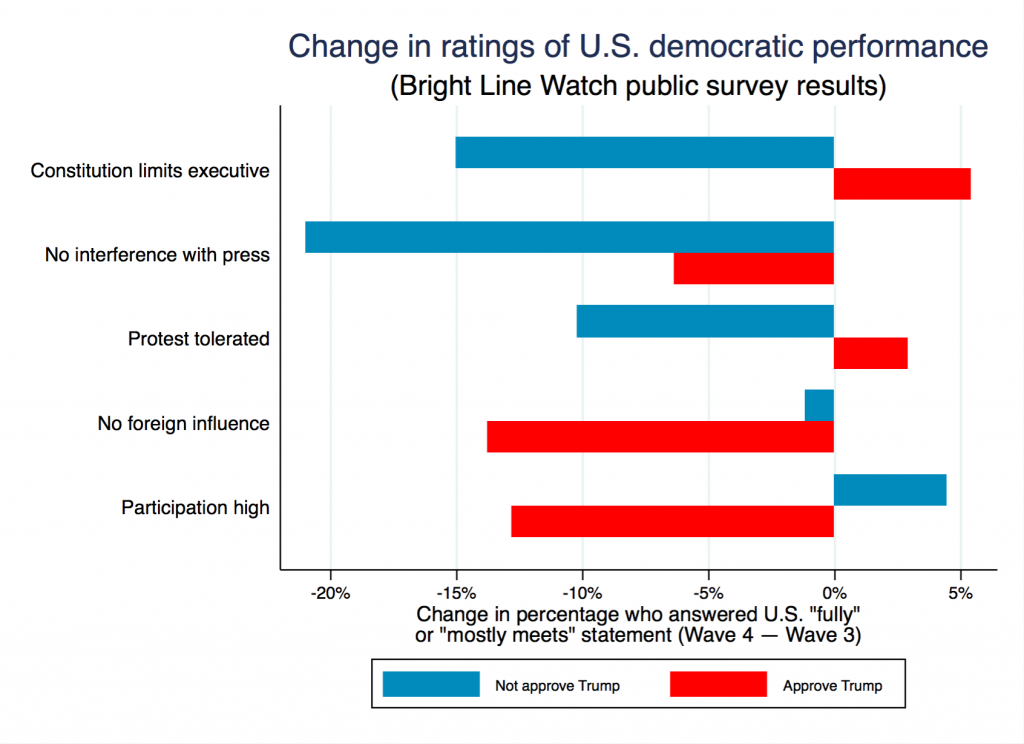

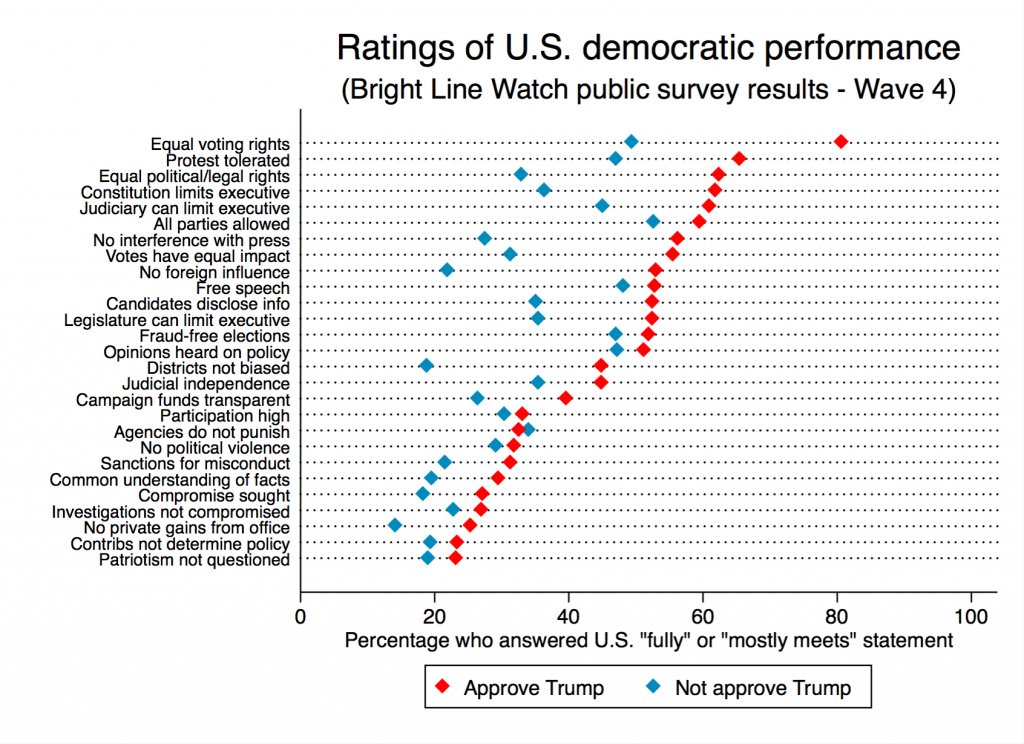

Were these perceived declines limited to one segment of the public or were they widely shared? Because President Trump is such a controversial and polarizing figure, we divided our respondent pool between those who approve of Trump’s job as president and those who disapprove. We then tested whether, on each of our 27 principles, the change in performance assessments between September 2017 (Wave 3) and January 2018 (Wave 4) was statistically different between Trump approvers and disapprovers. Interestingly, the downturn in perceived performance was widely shared. On 22 of the 27 statements, the change in performance ratings was not measurably different between supporters and opponents.

On five principles, we did find significant differences across the groups. The changes between September 2017 and January 2018 among Trump approvers (red) and disapprovers (blue) are illustrated in the next figure. Trump opponents perceived precipitous drops of between 10 and 22 percentage points on whether executive power can be expanded beyond constitutional limits, whether the government protects the rights of individuals to engage in peaceful protest (likely reflecting the recent controversy about N.F.L. players kneeling during the national anthem), and the freedom of news organizations from government interference, whereas the president’s supporters saw little or no deterioration. Trump’s rhetorical attacks on the media seem to have vexed his opponents far more than his supporters. Conversely, Trump approvers perceived sharp downturns in whether elections are free from foreign influence and rates of voter participation, while disapprovers held fast. These results suggest that the president’s supporters may be moving toward recognizing the legitimacy of concerns about foreign interference, though it should be noted that these results remain highly polarized: 53% of Trump supporters believe that elections are free of foreign influence, vs only 22% of Trump opponents. The results on participation may be suggestive of a feared or perceived disengagement heading into the midterm elections.

Comparing democracy in the U.S. to other countries

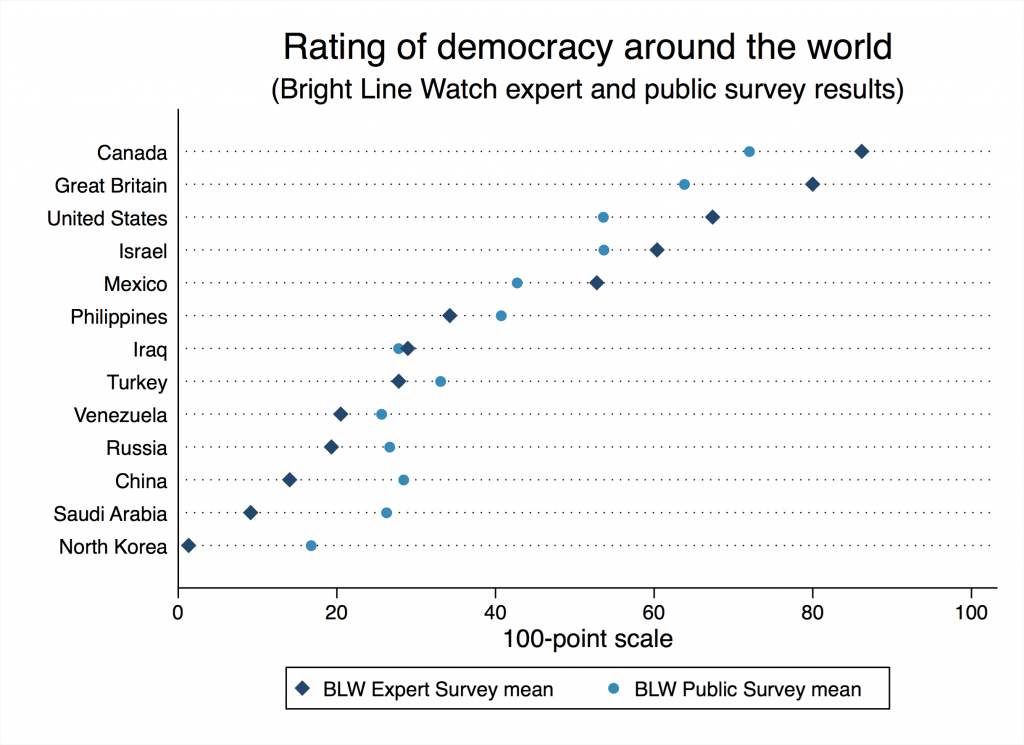

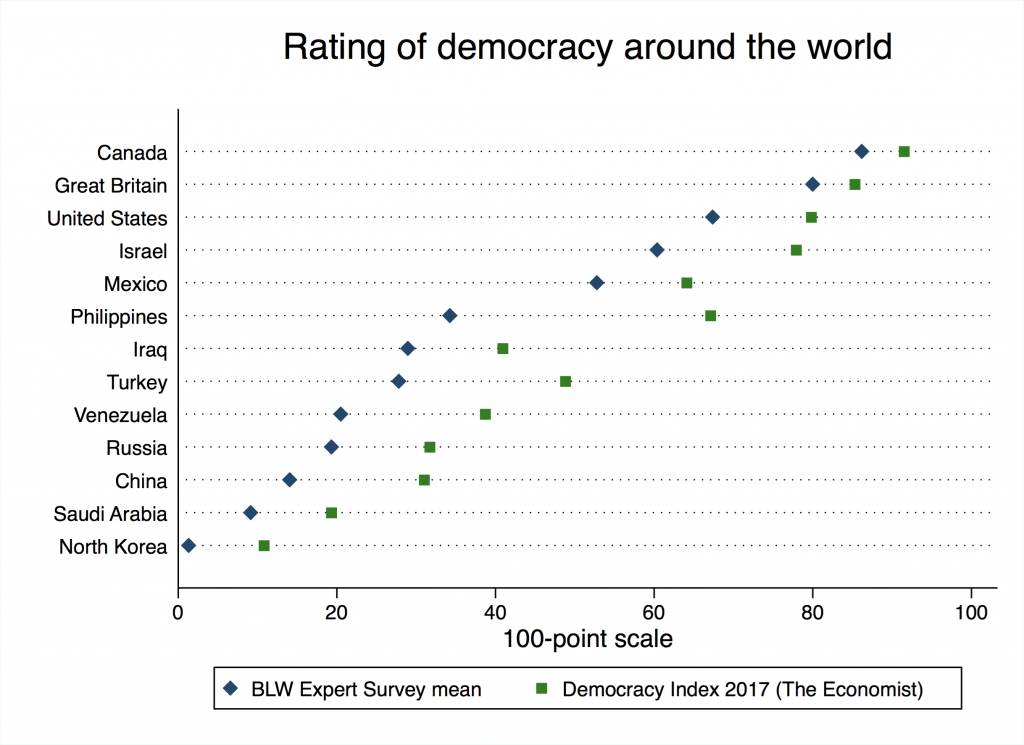

The Wave 4 surveys also asked respondents to rate democracy in the United States overall on a 100-point scale and then presented each respondent with six additional countries (randomly selected from a set of twelve) to rate on the same scale. The next figure juxtaposes the mean ratings of the expert and public samples. Though the rank orderings of experts and the public were nearly the same, experts perceived wider divergence in the quality of democratic governance between countries. Experts’ mean scores ranged from 1 for North Korea to 86 for Canada, while the public’s mean scores were more compressed (17 to 72).

Both experts and the public rated Canada and Great Britain higher than the United States. The United States’s closest “democratic neighbor” is Israel, which falls below the United States according to the experts, but just barely above it among the public. The full set of ratings indicates that the experts and the public largely see the world the same way (on average).

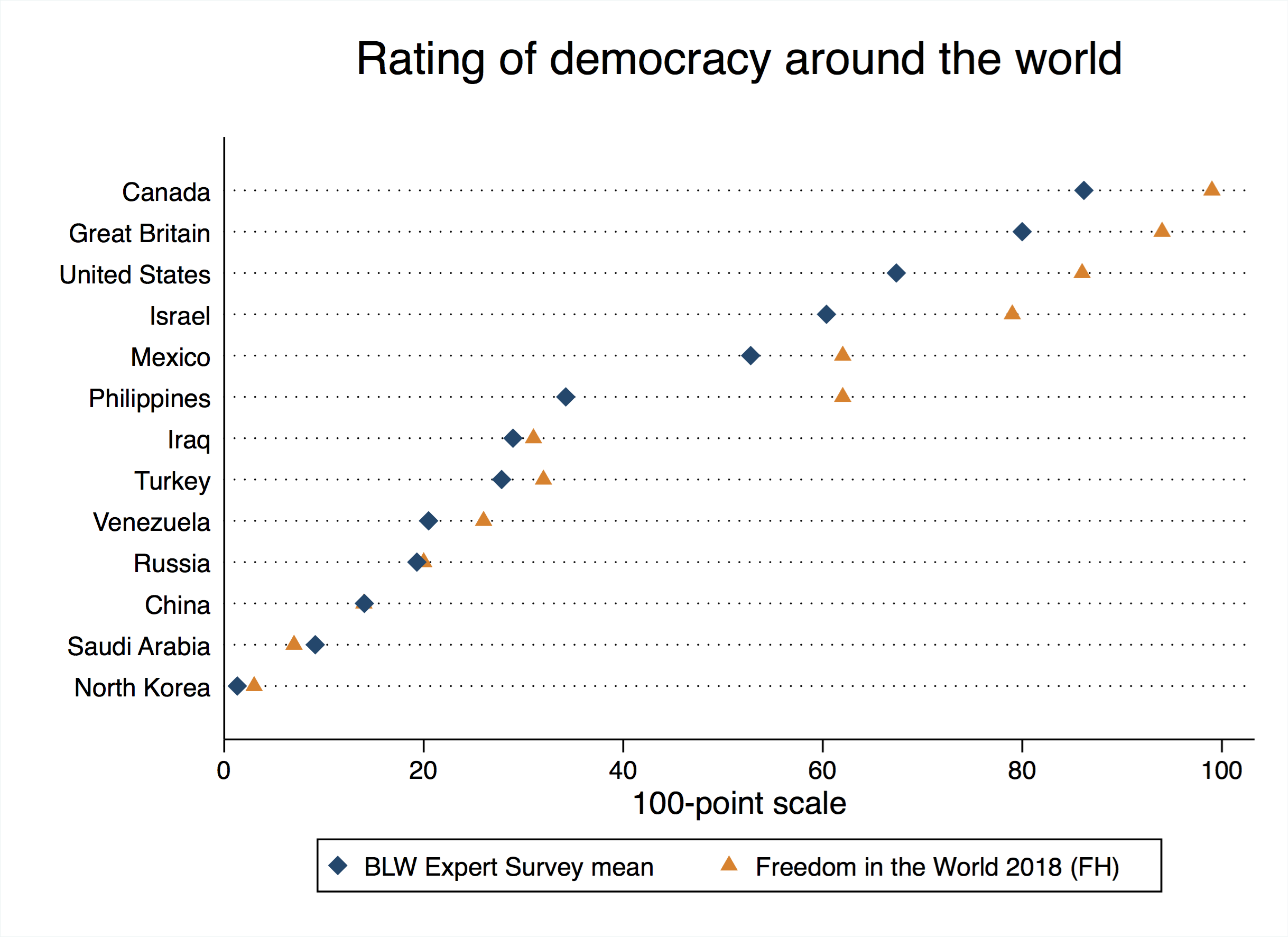

These country ratings correspond closely with other expert judgments: Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2018 report and The Economist’s Intelligence Unit’s 2017 Democracy Index. Both largely corroborate our cross-country comparisons. The Freedom House report rates every country on a 100-point scale as well. The figure below contrasts our mean expert survey score for each country with Freedom House’s rating. The indices track closely. Among non-democratic regimes, the numbers match nearly perfectly, though our experts are more circumspect about democratic quality at the high end of the scale than is Freedom House. We observe a similarly strong correlation between the Economist Intelligence Unit’s scores and our expert ratings, though in that case our expert ratings are lower across the board (see appendix Figure A2).

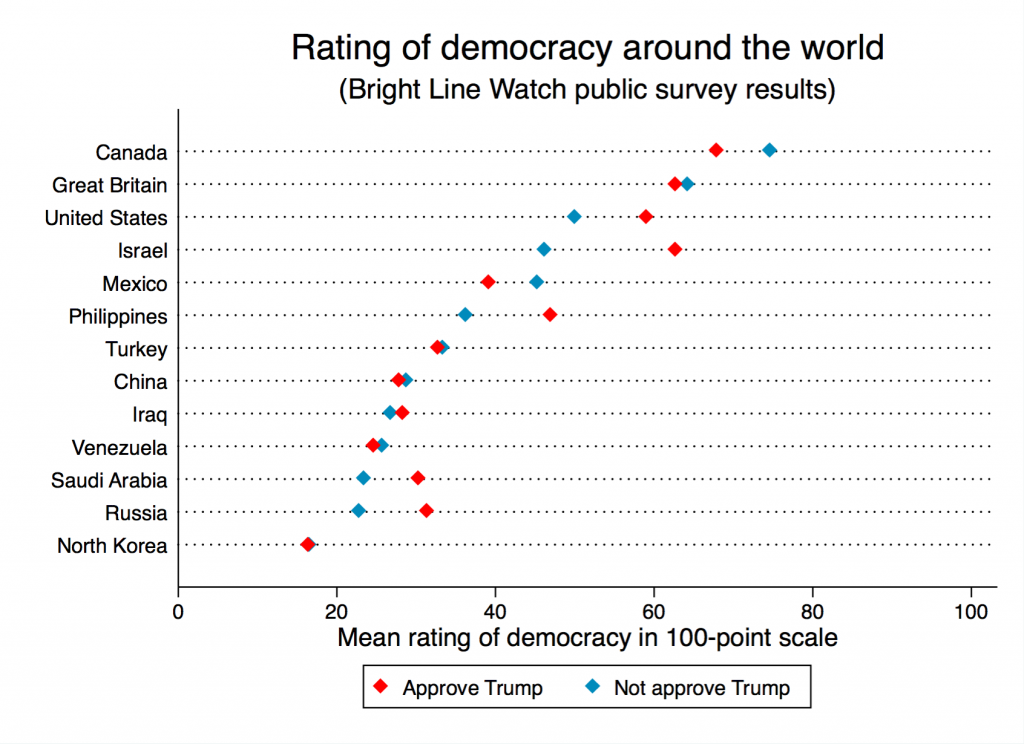

What about the public’s assessments of democracy around the world? The next figure breaks out ratings from President Trump’s approvers and disapprovers on our public survey. For many countries — including Great Britain, Turkey, China, Venezuela, and North Korea — the two groups’ ratings are essentially the same. For others, they diverge sharply. Trump supporters rate democracy in Israel 16 points higher than do his critics. They also rate the United States, the Philippines and Russia higher by about 10 points, and Saudi Arabia higher by seven. Trump’s critics, by contrast, rate U.S. neighbors Canada and Mexico higher than the president’s supporters do. Perhaps it is not surprising that Trump’s supporters view American democracy as stronger than his critics. But, when Trump speaks favorably of autocrats like Russian President Vladimir Putin, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and denigrates the governments of America’s closest allies, his supporters at home also appear to adjust their perceptions accordingly.

Is American democracy eroding?

Preoccupation about American democracy is generating a literary boom. A long list of prominent commentators, from David Frum to Michael Wolff to Yale psychiatrist Bandy Lee, worry openly that Donald Trump’s presidency represents a threat to American democracy. Others, including William Galston, Yascha Mounk, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, and E.J. Dionne, Thomas Mann, and Norman Ornstein, regard Trump’s presidency as a manifestation of trends that predate his political rise and that have reached countries beyond the U.S. Yet even those who regard Trump as a symptom of larger trends have raised alarms about his open contempt for democratic institutions and behavioral norms.

These fears are seemingly justified. Freedom House recently declared that 2017 “brought further, faster erosion of America’s own democratic standards than at any other time in memory, damaging its international credibility as a champion of good governance and human rights.” The Economist rated the U.S. as a “flawed democracy” for the second year in a row, and the Economist Intelligence Unit warned that further slippage is likely if polarization increases further. Bright Line Watch’s newest data echoes these more negative assessments.

This sense of alarm has also attracted critical pushback. On New Year’s Day, the Wall Street Journal derided those (including Bright Line Watch) who warned of potential peril to democracy over the past year as “progressive elites” who must be disappointed that Trump had not immediately revealed himself as a new Mussolini. Noting Trump’s policy frustrations on health care and the border wall, the Journal pronounced checks and balances to be robust and vowed to call out the president should he ever attempt to “exceed his constitutional power.”

The Journal’s commitment to protecting our democracy is heartening, but the results from our Wave 4 survey suggest that vigilance over the past year has been not misplaced. The downward trends on many of our 27 principles parallel the concerns raised in How Democracies Die, a new book from the political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. The authors provide abundant evidence that, when democracies around the world have eroded, the demise began when political leaders abandoned two critical behavioral norms — mutual toleration and forbearance. The first requires that politicians acknowledge the political legitimacy of their adversaries, while the second demands that those who hold the levers of state power refrain from using them to their fullest extent at every opportunity. By Levitsky and Ziblatt’s account, toleration and forbearance are the pillars on which all other democratic practices rest. Once those “master norms” cease to restrain political behavior, the broader array of democratic practices and principles comes under threat.

An emerging counter-argument to the Levitsky-Ziblatt thesis is that Trump’s incompetence and other personal foibles makes concern about actual democratic erosion unwarranted. As the Weekly Standard put it in their review of How Democracies Die, “The president certainly lacks a moral compass, is blinded by mind-boggling narcissism, has weak spots for despots, and is unfit for his job. But he is almost comically unfocused and pathetic. Does it make sense to call such an obviously weak leader a strongman?”

Can our surveys cast light on this debate? Although we do not measure perceptions of Trump’s fitness for office or his personal traits, the Bright Line Watch principles related to political discourse do speak directly to the master norms of toleration and forbearance:

- Political competition occurs without criticism of opponents’ loyalty or patriotism.

- Elected officials seek compromise with political opponents.

If Levitsky and Ziblatt are correct, then erosion on these two principles bodes ill for U.S. democracy. On this point, Bright Line Watch surveys provide only limited leverage, but also little reassurance. Our leverage is limited because, although changes on survey items corresponding to the master norms have been small, the scores on those items are so low across all survey waves that they could hardly have declined further. Among both the experts and the public, neither statement ever ranked higher than 20th out of 27 in performance on any survey. Indeed, all the principles we associate with informal behavioral norms — tolerance, forbearance, and common recognition of facts — consistently rank at the bottom among Bright Line Watch measures. Our surveys, then, might fail to detect the erosion Levitsky and Ziblatt warn against because the norms in question had collapsed long before our first survey in 2017.

How Democracies Die further suggests that erosion in other aspects of democracy could well follow a decline in the master norms. It would be premature to make strong conclusions about the fate of U.S. democracy, but the patterns we observe in this report hint at possible institutional decline. If scholars are right that erosion proceeds on a piecemeal basis, and that the first steps often entail targeting democracy’s “referees,” then our results regarding declines in judicial independence and support for a free press are especially disturbing.

The assessments of democracy outside the United States are similarly inauspicious. Levitsky and Ziblatt emphasize that partisan polarization is a key factor undermining mutual toleration. If we come to regard political adversaries not as principled opponents with whom we share a love of country but as dishonorable and possibly traitorous, then it is a small step to reject compromise altogether and to see accommodation within established democratic channels as a betrayal of one’s core principles. Polarization alters our perception of conflict and reduces our ability to see common ground. Unfortunately, it now pervades not only our respondents’ assessments of U.S. democratic performance, but even their assessments about democracy elsewhere. Trump’s supporters and opponents render divergent judgments on strongman rule in places like Russia and the Philippines and on our more democratic neighbors, Canada and Mexico. Americans now see the world, and democracy in the world, quite differently.

Appendix: Survey method, data, and instrument reliability

Bright Line Watch surveys on the state of America’s democracy, January 2018

From January 10–22, 2018, Bright Line Watch conducted its fourth survey on the state of democracy in the United States. We conducted previous surveys in February (Wave 1), May (Wave 2), and September (Wave 3) of 2017. Wave 1 and Wave 2 targeted expert respondents only. Wave 3 and Wave 4 have paired the expert survey with one drawing on a representative public sample.

-

Expert: On January 10, we sent email invitations to 9,423 political science faculty at universities in the United States. By January 22, after two reminder emails, we had complete responses from 1,066 (a response rate of 11%).

-

Public: YouGov fielded the public survey from January 10–18, producing 2,000 complete responses.

Participants in each Wave 4 survey responded to identical batteries of questions about democratic performance in the United States and in a dozen other countries. The data from both the expert and public surveys are available here. All analyses of the public data from YouGov incorporate survey weights.

The foundation of Bright Line Watch’s surveys is a list of 27 statements expressing a range of democratic principles. Democracy is a multidimensional concept. Our goal is to provide a detailed set of measures of democratic values and of the quality of American democracy. We are also interested in the resilience of democracy and the nature of potential threats it faces. Based on the experiences of other countries that have experienced democratic setbacks, we recognize that democratic erosion is not necessarily an across-the-board phenomenon. Some facets of democracy may be undermined first while others remain intact, at least initially. The range of principles that we measure allows us to focus attention on variation in specific institutions and practices that, in combination, shape the overall performance of our democracy.

Bright Line Watch’s Wave 1 survey included 19 statements of democratic principles. Based on feedback from respondents and consultation with colleagues, we expanded that list to 29 statements in Wave 2. We then reduced that set to what we intend to be a stable set of 27 statements for the Wave 3 and Wave 4 surveys. 17 of those 27 statements were included in Wave 1, and all 27 were included in Wave 2.

The full set of statements is presented below and grouped thematically for clarity. In the surveys, the principles were not categorized or labeled. Each respondent was shown a randomly selected subset of nine statements and asked to first rate the importance of those statements and then rate the performance of the United States on those dimensions.

27 statements of democratic principles

Elections

- Elections are conducted, ballots counted, and winners determined without pervasive fraud or manipulation

- Citizens have access to information about candidates that is relevant to how they would govern

- The geographic boundaries of electoral districts do not systematically advantage any particular political party

- Information about the sources of campaign funding is available to the public

- Public policy is not determined by large campaign contributions

- Elections are free from foreign influence

Voting

- All adult citizens have equal opportunity to vote

- All votes have equal impact on election outcomes

- Voter participation in elections is generally high

Rights

- All adult citizens enjoy the same legal and political rights

- Parties and candidates are not barred due to their political beliefs and ideologies

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in unpopular speech or expression

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in peaceful protest

- Citizens can make their opinions heard in open debate about policies that are under consideration

Protections

- Government does not interfere with journalists or news organizations

- Government effectively prevents private actors from engaging in politically-motivated violence or intimidation

- Government agencies are not used to monitor, attack, or punish political opponents

Accountability

- Government officials are legally sanctioned for misconduct

- Government officials do not use public office for private gain

- Law enforcement investigations of public officials or their associates are free from political influence or interference

Institutions

- Executive authority cannot be expanded beyond constitutional limits

- The legislature is able to effectively limit executive power

- The judiciary is able to effectively limit executive power

- The elected branches respect judicial independence

Discourse

- Even when there are disagreements about ideology or policy, political leaders generally share a common understanding of relevant facts

- Elected officials seek compromise with political opponents

- Political competition occurs without criticism of opponents’ loyalty or patriotism

The Wave 4 survey consisted of two main parts. In the first, each respondent was asked, “How well do the following statements describe the United States as of today?” Each respondent was then presented with 14 statements of principle, randomly drawn from the set above, and offered the following response options:

- The U.S. does not meet this standard

- The U.S. partly meets this standard

- The U.S. mostly meets this standard

- The U.S. fully meets this standard

- Not sure

The order in which statements were presented in each battery was randomized for each respondent so there should be no priming or ordering effects in how they were assessed.

After completing the battery on U.S. performance, we asked respondents to rate the overall quality of democracy in the United States today on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 is least democratic and 100 is most democratic.

We then presented respondents with a set of six countries, randomly selected from the list of 12 below, and asked them to rate the quality of democracy in each on the same 100-point scale they had just used to rate the United States.

- Canada

- China

- Great Britain

- Iraq

- Israel

- Mexico

- North Korea

- Philippines

- Russia

- Saudi Arabia

- Turkey

- Venezuela

While rating the six other countries, the score they had given to the United States was listed as a point of comparison on each respondent’s screen.

For the experts only, after they rated the other countries, we followed up by asking — for the six countries they had been selected to rate — whether they had ever taught about or conducted research on each country. This step allows us to identify experts with country-specific expertise.

For the public only, after rating the other countries, the survey concluded with a series of standard questions about demographics, political attitudes, and political knowledge.

Figure A1: U.S. democracy performance — public

Figure A2: Bright Line Watch expert assessments versus The Economist

Figure A3: Bright Line Watch public survey results by Trump approval