Since March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has transformed Americans’ lives and the practice of politics in this country. To date, more than 180,000 Americans have died. Many schools and workplaces have closed. Campaigns for the presidency, Congress, and other public offices are taking place in largely virtual form. During this period, protests against the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the government responses to those protests have also highlighted deep challenges to democratic governance. What effects have these dramatic events had? In its 11th survey of experts, conducted from July 27-August 17, 2020, Bright Line Watch invited political scientists across the country to assess the current state of U.S. democracy. In all, 776 respondents completed the survey.

Key findings:

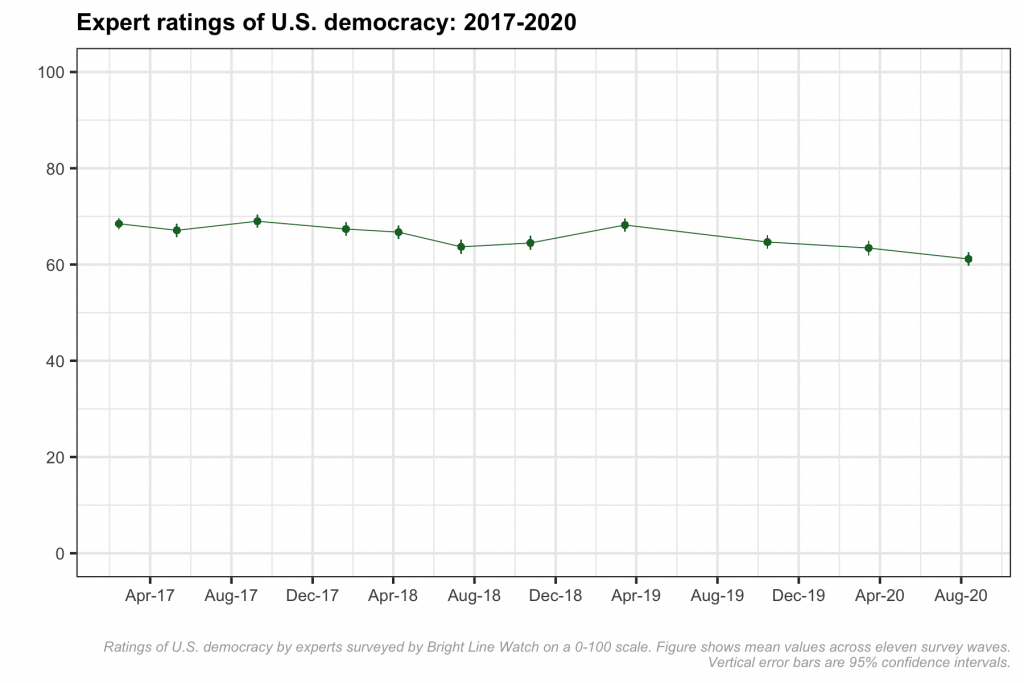

- Expert perceptions of overall performance of U.S. democracy continued an ongoing decline since spring 2019, reaching the lowest point since Bright Line Watch began its surveys in early 2017.

- Performance declines since March 2020 are greatest for protections of free speech, toleration of peaceful protest, and protection from political violence. Experts also report considerable declines since 2017 in performance on democratic principles concerning limits on government power and accountability for its misuse.

- Experts also express concerns about the state of American elections. Although relatively few express significant concerns about fraud, the majority does not believe that elections are free from foreign influence. Moreover, over two-thirds do not trust that citizens have an equal opportunity to vote or that all votes have equal impact.

- The gap between expert assessments of the importance of numerous principles and performance on those principles has widened. In the past, importance and performance ratings were highly correlated; experts perceived stronger performance for more important principles. That relationship has weakened.

Overall democratic performance — contemporary and historical

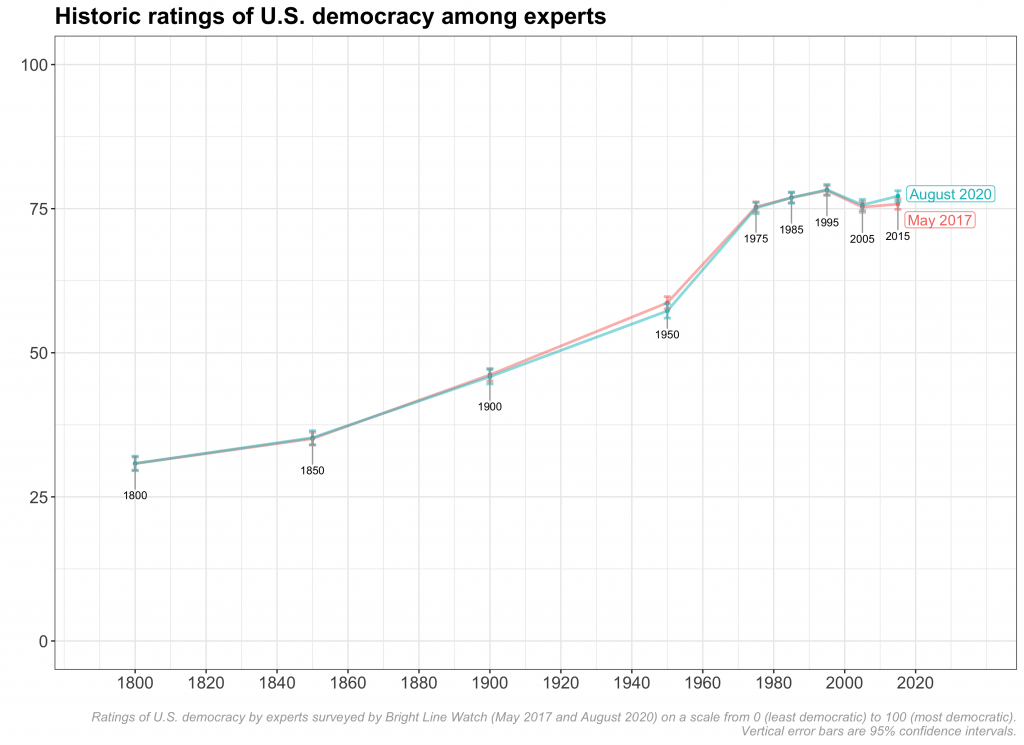

We find a small but perceptible drop in experts’ ratings of the overall quality of U.S. democracy. During the first two years of Bright Line Watch expert surveys, from February 2017 to March 2019, average scores were generally in the high 60s on a 0–100 scale, with a decline in the period before the 2018 midterm elections and then an uptick afterward in March 2019. Since then, however, three consecutive expert surveys have shown successive declines, driving ratings of U.S. democracy to a new low of 61 on our scale.

In the July-August 2020 survey, we asked our experts to make retrospective assessments on the same 0–100 democratic quality scale for nine years corresponding to distinct eras in American history: 1800, 1850, 1900, 1950, 1975, 1985, 1995, 2005, and 2015. The first four proceed in fifty-year increments to cover the time period shortly after the founding (1800), the middle of the 19th century but before the Civil War (1850), the era of progressive reforms but also Jim Crow in the South (1900), and the mid-20th century after the New Deal but before the peak of the civil rights movement (1950). We then solicit ratings for smaller intervals of 25 years and then 10 on the assumption that respondents’ knowledge and ability to discern differences in democratic quality improve as we approach the present day. Our final retrospective assessment covers 2015, which allows us to capture respondents’ judgments of U.S. democracy before the 2016 election campaign.

In a survey conducted in May 2017, we asked expert respondents to rate these same historical periods. We repeat the exercise in light of recent debates in academia, the news media, and mainstream political discourse that directly challenge previous historical conceptions of U.S. democracy. Prominent examples include the New York Times’s 1619 Project, which places slavery at the center of American history, and arguments that draw on critical race theory to advance claims for fundamental public policy changes to address profound political, economic, and social inequalities. Similarly, the protests that swept the country in summer 2020 were initially prompted by incidents of racialized violence in policing but grew to include challenges to monuments to historical figures and the narratives they embody.

We therefore replicated our historical survey battery to determine whether this sustained period of impassioned critique changed how experts assessed America’s democratic past. We find no evidence of such change.[1] Rather, we find remarkable consistency when we compare these responses to those from 2017. In both cases, we observe an upward trend from 1800 to 1950. (Our data do not allow us to capture some previous instances of democratic backsliding such as the erosion of a nascent multiracial democracy in the South after the Civil War.) Ratings of democratic quality rise most steeply between 1950 and 1975, the period of the civil rights movement. Ratings then stabilize in the 75–80 range for the 1975–2015 period. The consistency we observe between surveys suggests that our retrospective measures of democratic quality are reliable and valid, but also that the recent wave of critiques have not changed expert assessments.

Performance on democratic principles

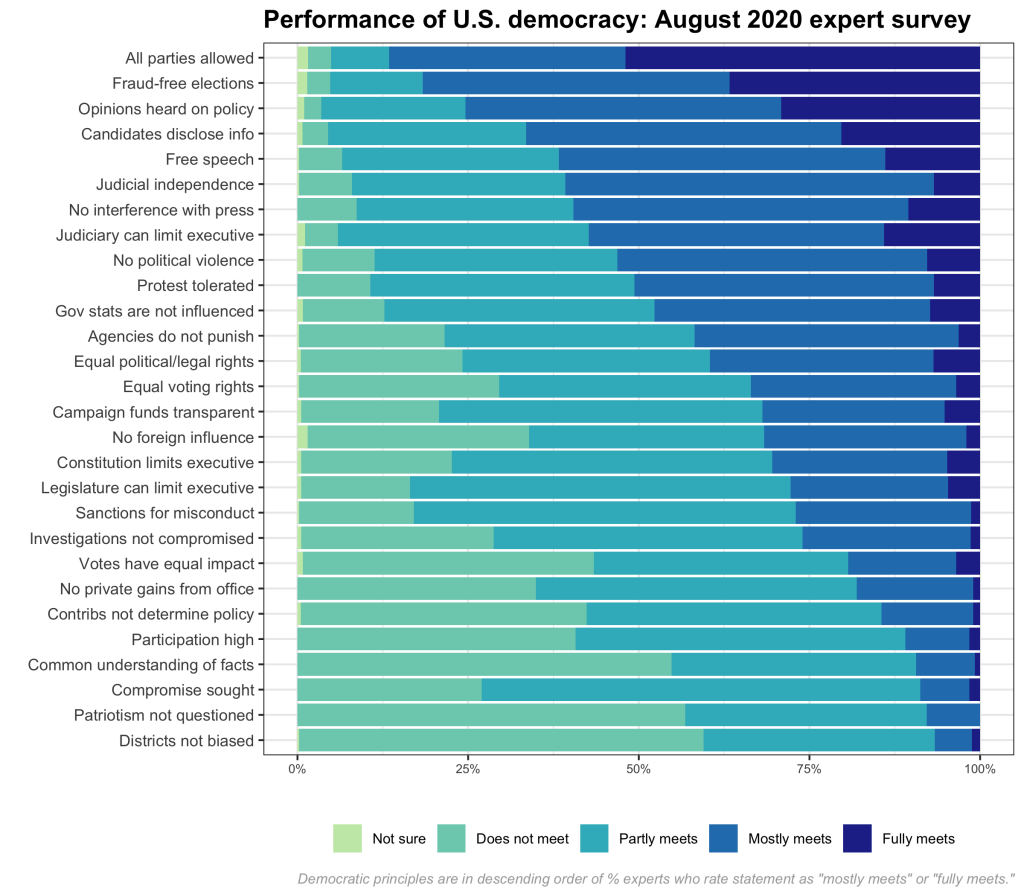

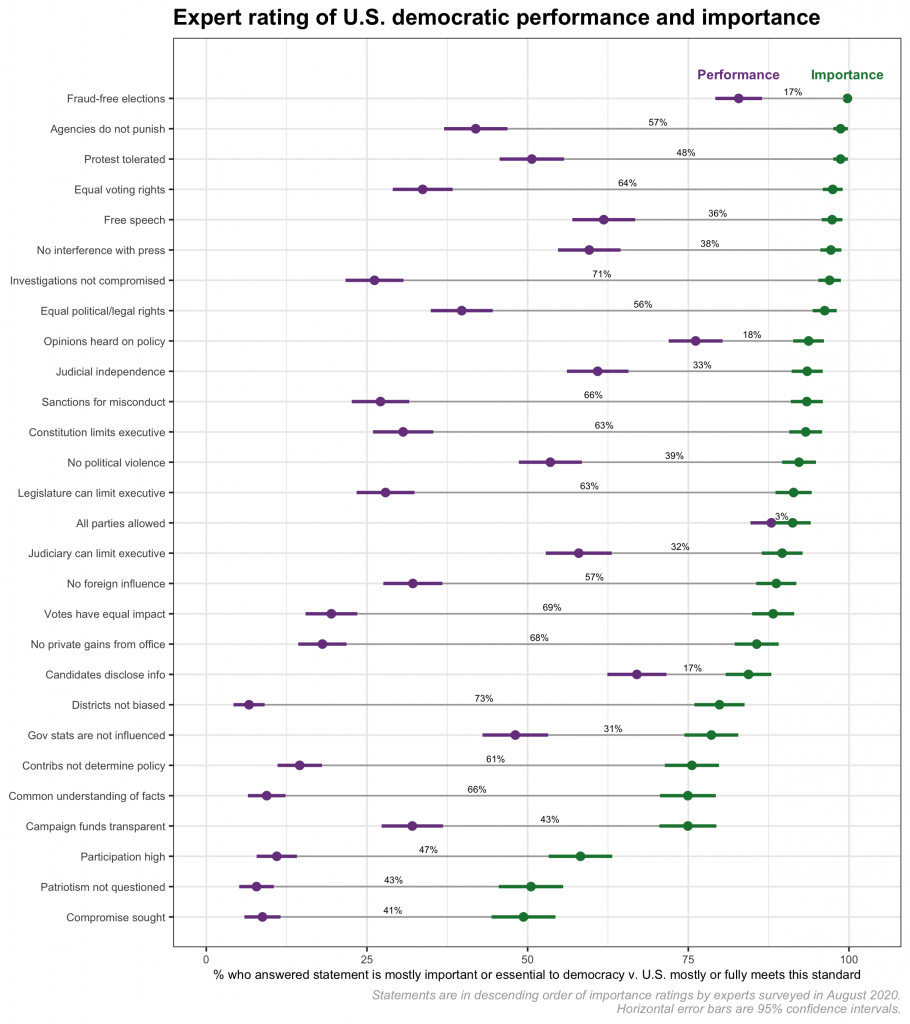

To disentangle performance on different aspects of democracy, we asked our sample of experts to gauge how well the U.S. “fully meets,” “mostly meets,” “partly meets,” or “does not meet” standards for 28 democratic principles (a list of the text of each is provided in the Appendix). The figure below presents the response distribution for each statement sorted by the proportion of respondents who consider the principle to be “mostly” or “fully” met.

In general, experts rate the U.S. as performing well on dimensions related to rights and freedoms (parties, opinions, speech). They rate it as performing poorly on dimensions associated with civility and behavior (patriotism, compromise, facts) and electoral dysfunction (biased districts, campaign contributions, inequality of votes). Experts express more mixed judgments on items involving accountability of office-holders and institutions. For instance, relatively fewer experts provide ratings at either extreme of the performance scale (i.e., “does not meet” or “fully meets”) for items that mention the ability of institutions (judiciary, legislature, the Constitution) to limit the executive.

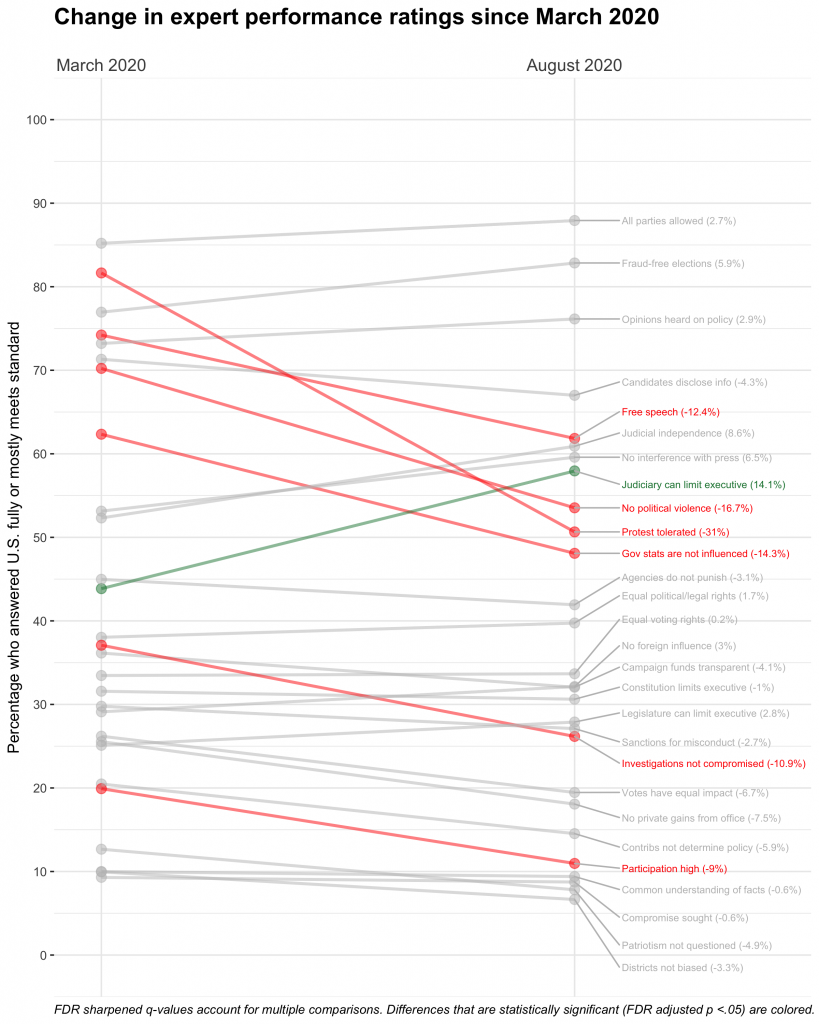

How have these perceptions shifted since our last expert survey in March 2020? We illustrate these changes in the figure below, which plots the percentage of respondents indicating that the U.S. “mostly” or “fully meets” the standard in question in our March and August 2020 expert surveys. Statistically significant differences are highlighted in color.[2]

Since March, experts perceive substantial declines in government protection for peaceful protests (-31%), prevention of political violence (-16.7%), and protections for free speech (-12.4%). These decreases are likely attributable to the administration’s responses to protests and demonstrations, including the use of non-lethal weapons against protestors and the deployment of federal agents in Portland and Washington, D.C. Expert ratings also declined for the principles that government statistics and data are not influenced by political considerations (-14.3%), investigations of public officials are free of political interference (-10.9%), and that voter participation in elections is generally high (-9%).

The only statistically significant improvement in performance we observe is on the principle that the judiciary can effectively limit the executive, which rose from 44% to 58% saying that the U.S. mostly or fully meets this standard. This increase might reflect recent court decisions that prevented President Trump from blocking the release of his financial records and overturned his decision to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. It is also possible that the increase represents a regression to the mean after the March 2020 survey, when many items linked to institutional accountability sank to record lows.

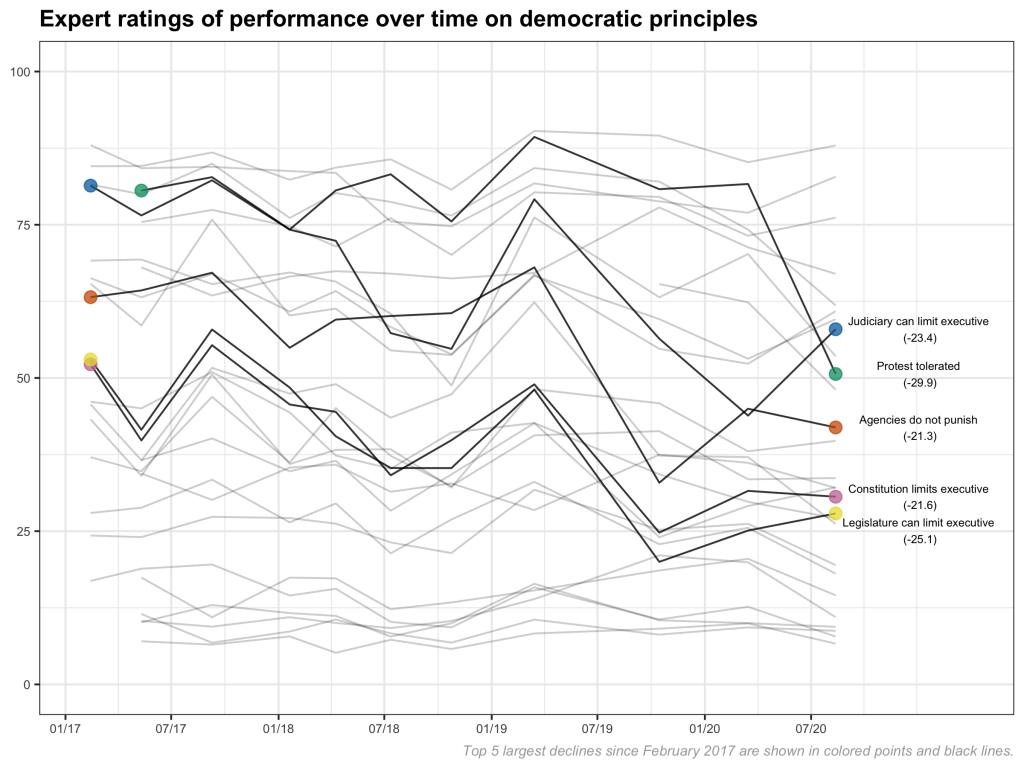

To put the declines we observe in a long-term context, we plot the evolution of each item since spring 2017 in the figure below, which lists the five items on which expert ratings of U.S. democratic performance have fallen the furthest since we began our surveys:

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in peaceful protest

- Executive authority cannot be expanded beyond constitutional limits

- The legislature is able to effectively limit executive power

- The judiciary is able to effectively limit executive power

- Government agencies are not used to monitor, attack, or punish political opponents

As the figure illustrates, the first item, which measures government toleration of protest, was high and generally stable until our most recent survey, when it plunged thirty percentage points (as discussed above). The magnitude of this decline rivals the reduction for the principle that government agencies not be used to punish political opponents that followed the discovery of the President’s efforts pressuring the Ukrainian government to investigate Joe Biden (the final item on the list). The next three items reflect our experts’ diminished confidence in the effectiveness of institutional checks on executive authority since 2017. All four of these items declined sharply between March and October 2019 and have not rebounded substantially in the period since.

The importance-performance gap for democratic principles

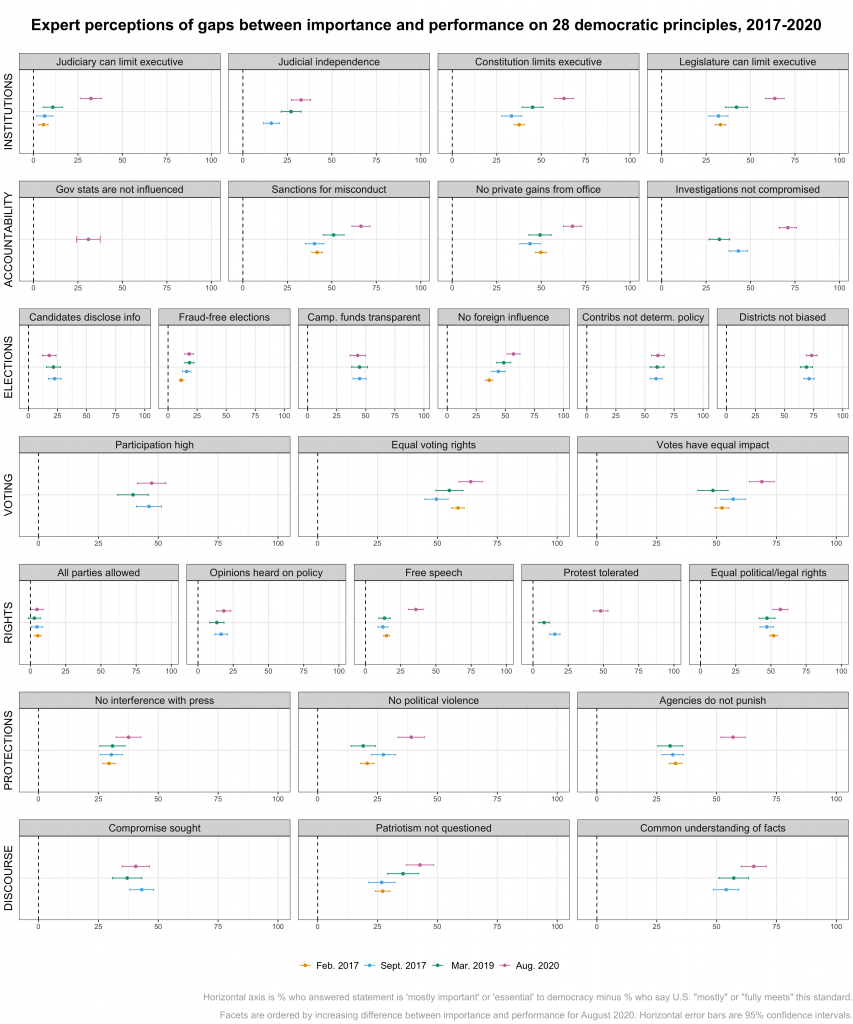

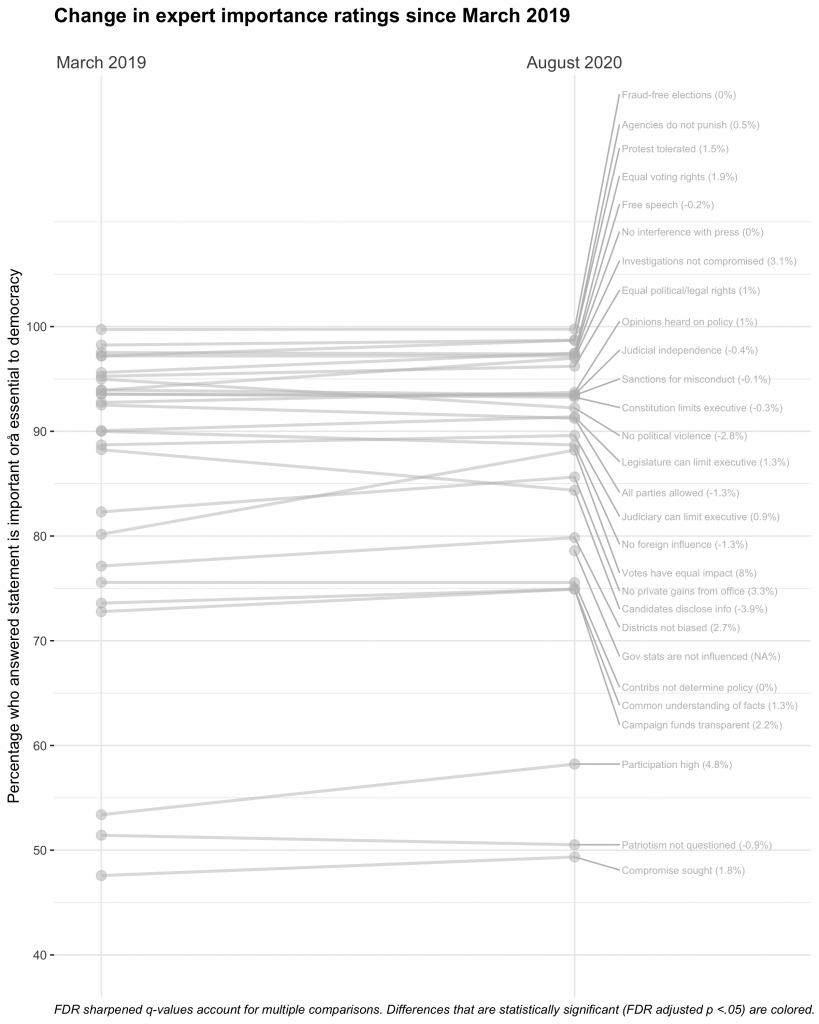

The declines in democratic performance that we observe on a number of principles are discouraging, but the substantive relevance of these changes depends on how crucial each principle is to democracy. In addition to gauging performance on each democratic principle, our survey also asked respondents to rate the importance of each characteristic to democratic government as “not relevant,” “beneficial,” “important,” or “essential.” We have measured the importance of these principles four times since we began our surveys in 2017.[3] In contrast with performance (which we have measured eleven times), importance assessments are remarkably stable.[4]

The figure below highlights the difference between the percentage of experts rating each principle as “mostly important” or “essential” to democracy and the percentage saying the U.S. “mostly” or “fully meets” the standard in question for each principle. For example, if 95% of experts viewed free and fair elections as essential or important for democracy, but only 80% believed that the United States is fully or mostly meeting this standard, then we would have a deficit of 15 percentage points, the value plotted on the horizontal axis. Dots further to the right indicate that a greater percentage of experts rate the principle as important relative to the percentage who rate the U.S. as performing well on it. The panels show this gap for a different democratic principle across each of the four waves in which importance and performance were measured, allowing us to see how gaps have changed over time.

We find substantial gaps between importance and performance. With just a few exceptions, these have either widened since 2017 (i.e., dots move rightward across waves) or have been consistently wide (i.e., located relatively far from zero) since we began polling experts.

The largest importance-performance gaps are for principles related to institutions and accountability, where differences between importance and performance frequently exceed 50 percentage points and have markedly increased over the course of the Trump administration. For example, the difference between importance and performance for constitutional limits on the executive stood at around 30 percentage points when we began polling experts in 2017. By August 2020, the gap had grown to 60 percentage points. Measures for impartial investigations, sanctions against misconduct, legislative limits on the executive, and agencies not punishing political opponents show similar trajectories.

Heading into the 2020 election, the picture for elections and voting is also troubling. Many related principles show a difference of fifty percentage points or more. A number of these principles (participation, contributions determining policy, equal voting rights, districts not biased) have been underperforming consistently since we began our surveys. The most recent survey also shows an increased gap on whether votes have equal impact, perhaps owing to concerns about the potential for another inversion in which the Electoral College winner loses the popular vote in November. In addition, the importance/performance gap for foreign influence on the elections now surpasses 50 percentage points, highlighting concerns that will likely intensify with the Trump administration’s recent move to end in-person intelligence briefings to Congress about foreign interference in elections.

We see large gaps emerging, as mentioned, on principles related to rights and protections, including protests being tolerated, free speech, and political violence, as well as a slight widening of the difference between importance and performance for equal political and legal rights and no interference with the press.

Several items on our surveys concern political discourse. Our experts have seen willingness to compromise as fairly stable since 2017. However, the importance-performance gap has grown on questioning the opposition’s patriotism and cross-party common understanding of facts.

Rating the normalcy and importance of recent events

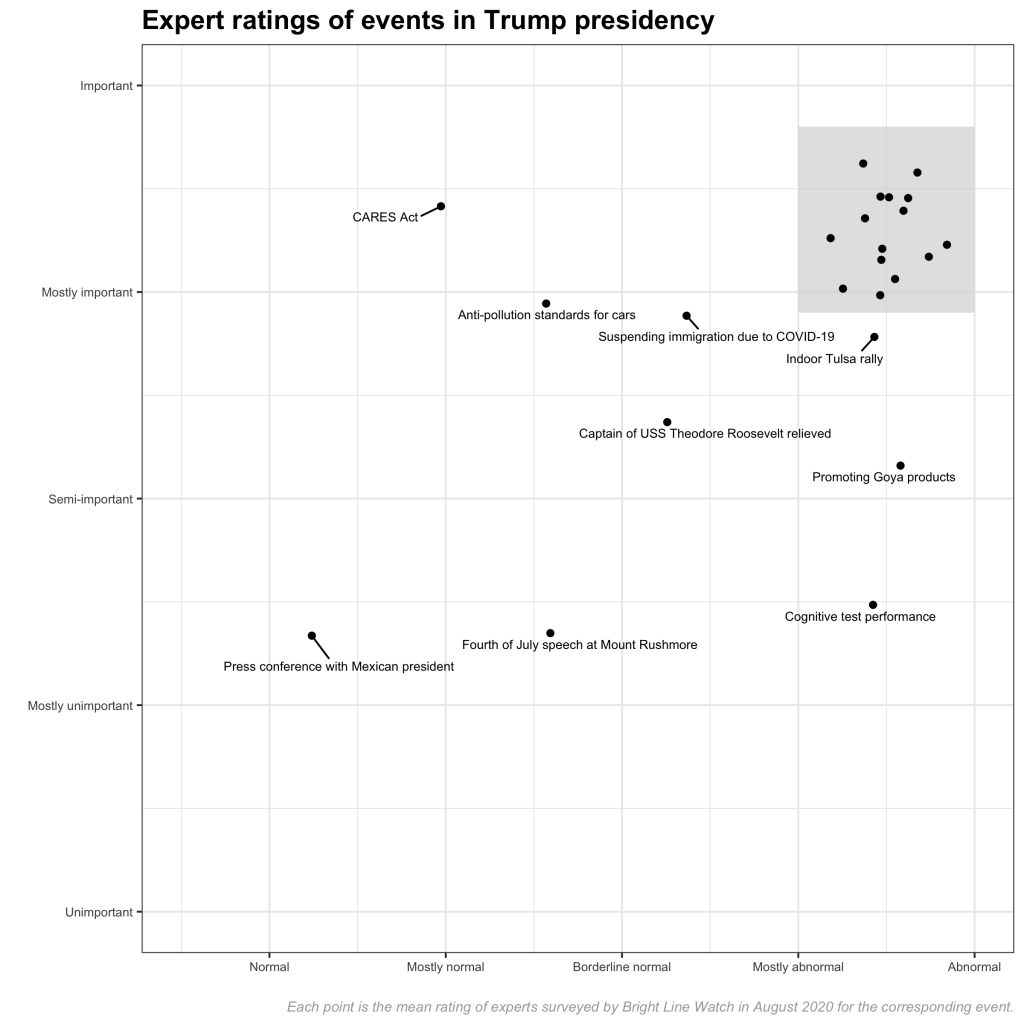

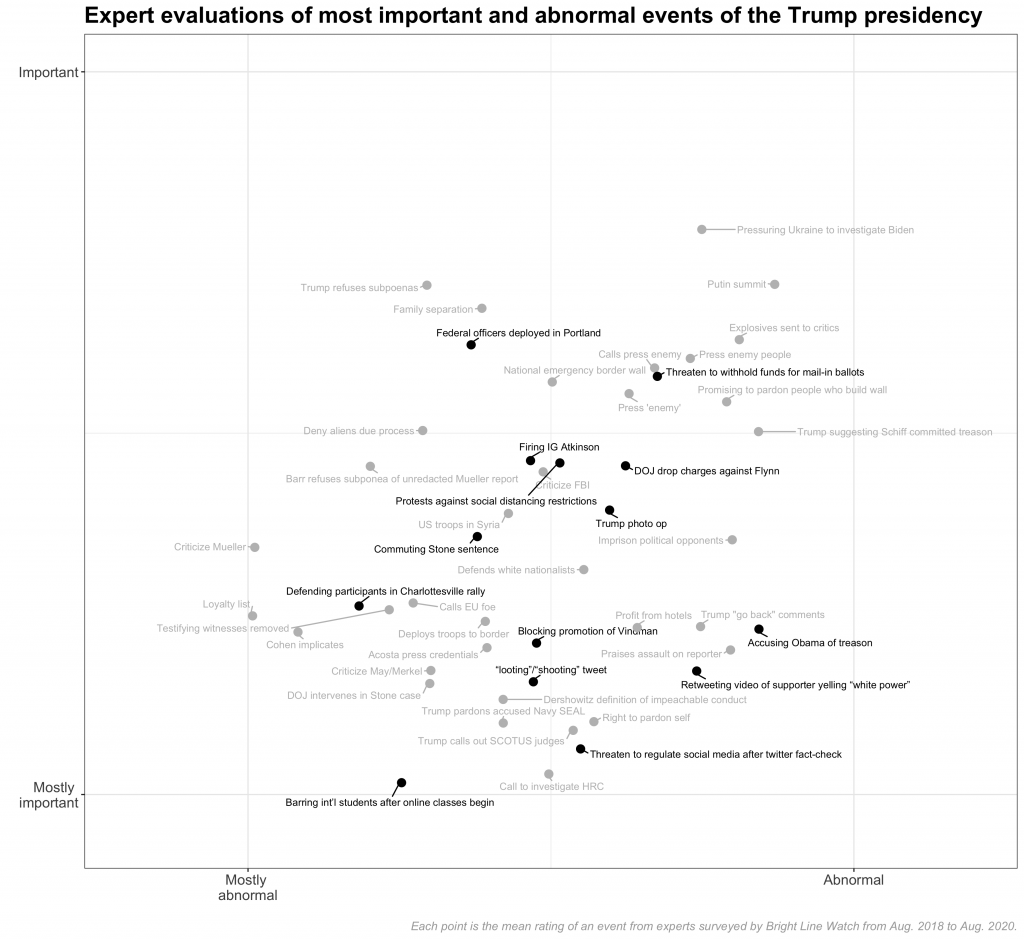

As in prior surveys, we asked experts to assess the importance and normalcy of several notable events that took place since our last report in March. Experts classified each event on separate five-point scales that ranged from unimportant to important and from normal to abnormal, respectively.

The results are presented in the figure below. Routine activities of little importance lie in the lower-left quadrant. Points situated in the upper-right quadrant represent events that experts deem highly unconventional and consequential; these are often major departures from democratic norms. For example, holding a joint press conference with Mexico’s president is business as usual and thus rated as both normal and unimportant, while the Justice Department’s decision to drop charges against former national security advisor Michael Flynn was rated as important and outside established norms.

Events regarded as both important and abnormal are abundant in the figures below. The dense cluster of unlabeled points in the shaded box in the first figure below corresponds to those labeled with black text in a magnified version of that same sector presented in the second figure. The second figure puts the most recent set of important and abnormal events in the context of all such events we have tracked during the Trump presidency, contrasting events that occurred after March 2020 (in black) with those from previous surveys (in grey).

Experts view the persistent attacks and misinformation on mail-in voting by President Trump as the most important and most abnormal incidents that occurred since March, though they did not view any recent event as being as abnormal and consequential as the Trump-Putin summit in 2018.

We note, however, the challenge of discriminating between what is normal or abnormal in the midst of a global pandemic. Many experts expressed this difficulty in their comments, particularly for policies directly linked to the pandemic. For instance, one expert writes of the CARES Act: “Clearly a $2 trillion appropriation is abnormal because the crisis is abnormal. But it was the normal functioning of the system.” Similarly, another expert described the suspension of immigration due to COVID-19 as “a normal response to an abnormal situation.”

Notes

[1] Although the average score for 2015 in our most recent survey is slightly higher than the same rating from our prior historical survey, the difference between the estimates is not statistically significant.

[2] We calculate sharpened FDR q‑values to compare against false positives due to multiple comparisons. In graphs that show changes in performance and importance ratings, only values below the conventional 0.05 significance threshold are colored.

[3] Note that this most recent survey includes only our expert respondents, not an accompanying representative sample of the American public. Future surveys will again include public samples.

[4] For example, none of the 28 principles showed a statistically significant change in importance ratings since the last time we asked respondents about the importance of each democratic principle (March 2019; see Figure A1 in the Appendix).

Appendix

Bright Line Watch expert survey on the state of American democracy, August 2020

From July 27 to August 17, 2020, Bright Line Watch conducted its eleventh survey of academic experts on the quality of democracy in the United States. We surveyed 776 political science experts across a diverse range of subfields (7.5% of solicited invitations). Our email list was constructed from the faculty list of U.S. institutions represented in the online program of the 2016 American Political Science Association conference.

Data from the expert survey are available here.

28 statements of democratic principles

The foundation of Bright Line Watch’s surveys is a list of 28 statements expressing a range of democratic principles (the full list is provided below). Democracy is a multidimensional concept. Our goal is to provide a detailed set of measures of democratic values and of the quality of American democracy. We are also interested in the resilience of democracy and the nature of potential threats it faces. Based on the experiences of other countries that have experienced democratic setbacks, we recognize that democratic erosion is not necessarily an across-the-board phenomenon. Some facets of democracy may be undermined first while others remain intact, at least initially. The range of principles that we measure allows us to focus attention on variation in specific institutions and practices that, in combination, shape the overall performance of our democracy.

Bright Line Watch’s Wave 1 survey included 19 statements of democratic principles. Based on feedback from respondents and consultation with colleagues, we expanded that list to 29 statements in Wave 2. We then reduced that set to a set of 27 statements for the Wave 3 through Wave 8 surveys. 17 of those 27 statements were included in Wave 1, and all 27 were included in Wave 2. We added one statement to the list in Wave 9.

The full set of statements is presented below and grouped thematically for clarity. In the surveys, the principles were not categorized or labeled. Each respondent was shown a randomly selected subset of 14 statements and asked to rate the performance of the United States on those dimensions.

Elections

- Elections are conducted, ballots counted, and winners determined without pervasive fraud or manipulation

- Citizens have access to information about candidates that is relevant to how they would govern

- The geographic boundaries of electoral districts do not systematically advantage any particular political party

- Information about the sources of campaign funding is available to the public

- Public policy is not determined by large campaign contributions

- Elections are free from foreign influence

Voting

- All adult citizens have equal opportunity to vote

- All votes have equal impact on election outcomes

- Voter participation in elections is generally high

Rights

- All adult citizens enjoy the same legal and political rights

- Parties and candidates are not barred due to their political beliefs and ideologies

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in unpopular speech or expression

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in peaceful protest

- Citizens can make their opinions heard in open debate about policies that are under consideration

Protections

- Government does not interfere with journalists or news organizations

- Government effectively prevents private actors from engaging in politically-motivated violence or intimidation

- Government agencies are not used to monitor, attack, or punish political opponents

Accountability

- Government officials are legally sanctioned for misconduct

- Government officials do not use public office for private gain

- Law enforcement investigations of public officials or their associates are free from political influence or interference

- Government statistics and data are produced by experts who are not influenced by political considerations

Institutions

- Executive authority cannot be expanded beyond constitutional limits

- The legislature is able to effectively limit executive power

- The judiciary is able to effectively limit executive power

- The elected branches respect judicial independence

Discourse

- Even when there are disagreements about ideology or policy, political leaders generally share a common understanding of relevant facts

- Elected officials seek compromise with political opponents

- Political competition occurs without criticism of opponents’ loyalty or patriotism

To measure perceived democratic performance, the survey asked, “How well do the following statements describe the United States as of today?” Each respondent was then presented with 10 statements of principle, randomly drawn from the set above, and offered the following response options:

- The U.S. does not meet this standard

- The U.S. partly meets this standard

- The U.S. mostly meets this standard

- The U.S. fully meets this standard

- Not sure

To measure the perceived importance of each principle, the survey asked, “How important are these characteristics for democratic government?” Each respondent was then presented with 10 statements of principle, randomly drawn from the set above, and offered the following response options:

- Not relevant: this has no impact on democracy

- Beneficial: this enhances democracy but not required for democracy

- Important: if this is absent, democracy is compromised

- Essential: A country cannot be considered democratic without this

The order in which statements were presented in both batteries was randomized for each respondent so there should be no priming or ordering effects in how they were assessed.

Full description of events

- President Trump deploys federal law enforcement officers to Portland, Oregon and other cities.

- President Trump commutes the sentence of Roger Stone, who was convicted of seven felonies for obstructing a congressional investigation into Mr. Trump’s 2016 campaign.

- President Trump threatens to withhold funds from Michigan and Nevada for their use of mail-in ballots in primaries during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- President Trump fires Inspector General Michael Atkinson months after Atkinson raised concerns that eventually led to Trump’s impeachment in the House.

- The Justice Department moves to drop charges against former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn after he had already pled guilty to them in court.

- President Trump retweets a video of a supporter yelling “white power.”

- The Trump administration blocks the promotion of impeachment witness Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, leading him to resign from the Army.

- Law enforcement officers use chemical irritants against protestors outside the White House, clearing a path for President Trump to take a photo outside St. John’s Church

- President Trump posts a tweet decrying protests against police violence in Minneapolis that includes the phrase “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

- President Trump defending participants in a white-nationalist rally in Charlottesville, VA, saying there were “very fine people on both sides.”

- President Trump encourages far-right political groups to protest social distancing restrictions and calls on states to lift restrictions.

- President Trump threatens to “regulate” or “close” down social media platforms after Twitter added a fact-check to one of his tweets.

- President Trump temporarily suspends all immigration to the United States in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- President Trump holds an indoor campaign rally in Tulsa against advice from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and requires attendees to sign a legal release.

- President Trump promotes Goya food products from the Oval Office.

- The captain of the USS Theodore Roosevelt is relieved of command for going outside the chain of command after an outbreak of the novel coronavirus on board.

- President Trump repeatedly mentions his performance on a cognitive test.

- President Trump issues a tweet threatening the tax status of educational institutions who engage in “indoctrination.”

- President Trump accuses former President Barack Obama of treason.

- The House and Senate approve and President Trump signs the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act).

- The Trump administration releases plan to freeze anti-pollution and fuel-efficiency standards for cars.

- The Trump administration attempts to bar visas to all international students whose classes have gone online.

- President Trump gives a Fourth of July speech at Mount Rushmore.

- President Trump holds a joint press conference with Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador at the White House.