The Big Lie among state legislators

Measuring the prevalence and correlates of 2020 election denial

Introduction

How committed are political elites to the basic norms of democracy? Classic accounts of democratic resilience in the United States suggest that political elites almost uniformly subscribe to the ideals of liberal democracy and that they play a key role in safeguarding it. However, recent events raise concerns that some elected officials may not defend democracy and might even undermine it.

The 2020 presidential election and its aftermath provided compelling evidence for both propositions. On the one hand, incumbent president Donald J. Trump refused to acknowledge his loss and fomented a violent attack on the Capitol in an attempt to stop congressional certification of the election results. On the other hand, key political actors from Trump’s own party resisted pressure to manipulate the election results and proved instrumental in ensuring a peaceful transfer of power. The lessons to be drawn from the 2020 election are decidedly contradictory: the election was both “a miracle and a tragedy,” simultaneously improving and wounding faith in the commitment of elites to democratic norms.

Understanding the behavior of political elites is thus crucial as we approach the 2024 election. Media attention to election denial was greatest for Trump and his allies in Congress, of course. Similarly, numerous Republican candidates for statewide elected office in 2022 did not recognize the results of the 2020 presidential election. However, we know much less about the behavior of lower-level officials – a major blind spot given the key role of states in conducting elections, America’s history of subnational authoritarianism, and the potential for state-level democratic backsliding.

In this project, we measured the prevalence of election fraud claims in tweets from state legislators drawing on data from December 2020-February 2023. Our main findings were as follows:

-

Republican state legislators made or endorsed claims of election fraud over 2,000 times on Twitter.

-

However, this activity was heavily concentrated among a handful of legislators and states (most notably in Arizona).

-

Finally, state legislator ideological extremity is a strong predictor of Twitter endorsement of election fraud claims, whereas the ideology of constituents was not.

Democratic erosion from the top

A recent literature in political science has highlighted the conditional nature of citizens’ commitment to democracy: the vast majority express support for democracy in principle but many fail to sanction norm violations from parties or candidates they support. Citizens’ conceptions of those norms themselves are also malleable – people may rationalize transgressive actions taken on behalf of policies one favors. The public cannot be counted on to act as a bulwark against democratic erosion.

Given these vulnerabilities, prominent scholarship has cast political elites as crucial defenders of democratic norms against populist authoritarian impulses. Yet the commitment of American political elites to the basic norms of democracy, long assumed to be nearly universal, appeared to soften in the last few years as officials across the country pursued partisan objectives at the expense of core democratic values.

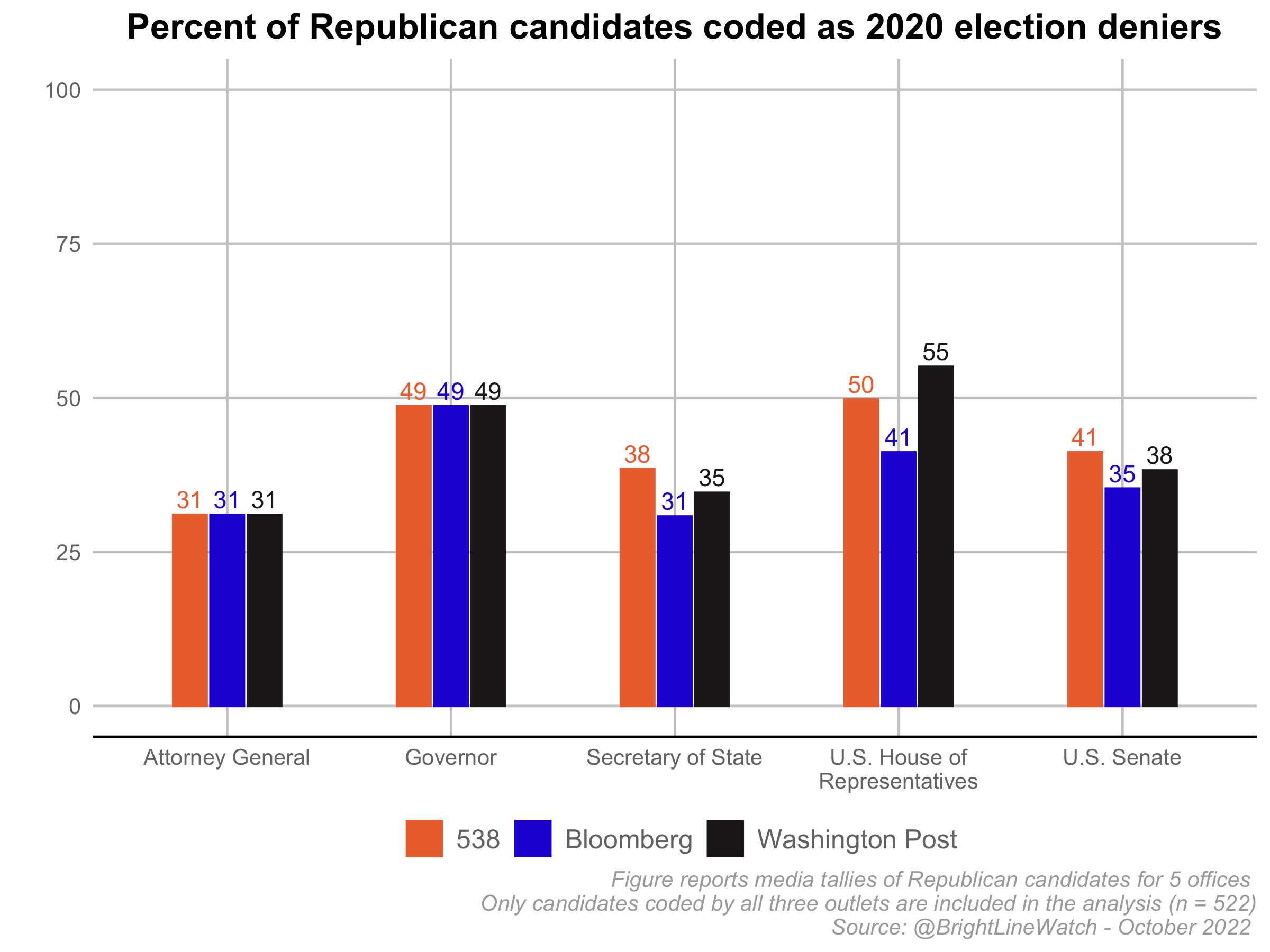

The 2020 presidential election exemplified this trend: despite the absence of evidence that fraud altered the outcome of the election, many Republicans at all levels of government refused to accept Joe Biden as the rightful winner. News organizations including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Bloomberg published systematic tallies of election-denying candidates for various high-level offices. The results underscored the gravity of the situation: nearly a third of Republican candidates for Attorney General and approximately half of Republican candidates for U.S. House did not accept the results of the 2020 election.

Whether individuals in positions of power accept the results of elections and abide by democratic norms while in office matters for democracy. First, elected officials shape democratic performance through their exercise of their formal powers. In the United States, which has an unusually decentralized election administration system, state officials play a large role in determining who is allowed to vote and how congressional districts are drawn. In addition, elected officials exert an important indirect influence on democratic performance. Through their words and actions, individuals who hold formal power can influence the political environment. Recent research shows that norms of behavior are powerfully shaped by elite rhetoric: what politicians say and do sets the tone for constituent conduct and attitudes. Candidates and officeholders who reject the results of an election, regardless of the strength of evidence underlying their claims, can weaken the public’s confidence in elections.

The behavior of higher-level elected officials, such as governors and members of Congress, is concerning and worthy of attention. However, other officeholders with substantial influence on election administration – both formal and informal – have received less scrutiny. In particular, the role of state legislators in propagating false claims about election security deserves more attention. This project examines the behavior of these important but largely overlooked political actors. Scholarship on representation in state legislatures shows that mechanisms of accountability are weak, which makes detailed and systematic investigations of their members’ conduct even more important.

Social media data collection

In the past, both Republicans and Democrats have expressed doubts about the legitimacy of election results. However, questions about the legitimacy of the 2020 election have been raised almost exclusively by Republicans. We therefore focus on the behavior of GOP state legislators.

We constructed a list of over 7,000 state Republican legislators in all 99 legislative chambers across all 50 states using data from Ballotpedia, an online political encyclopedia. We then scraped legislators’ Twitter and Facebook posts from December 2020-February 2023 and used keyword searches to identify tweets about election fraud. Each post was then read by at least two human coders who coded whether it endorsed claims that the 2020 presidential election was marred by fraud. In total, we identified a total of 2,268 tweets by U.S. state legislators that promote election fraud claims during the study period. (The appendix includes a detailed description of our methods.)

Results

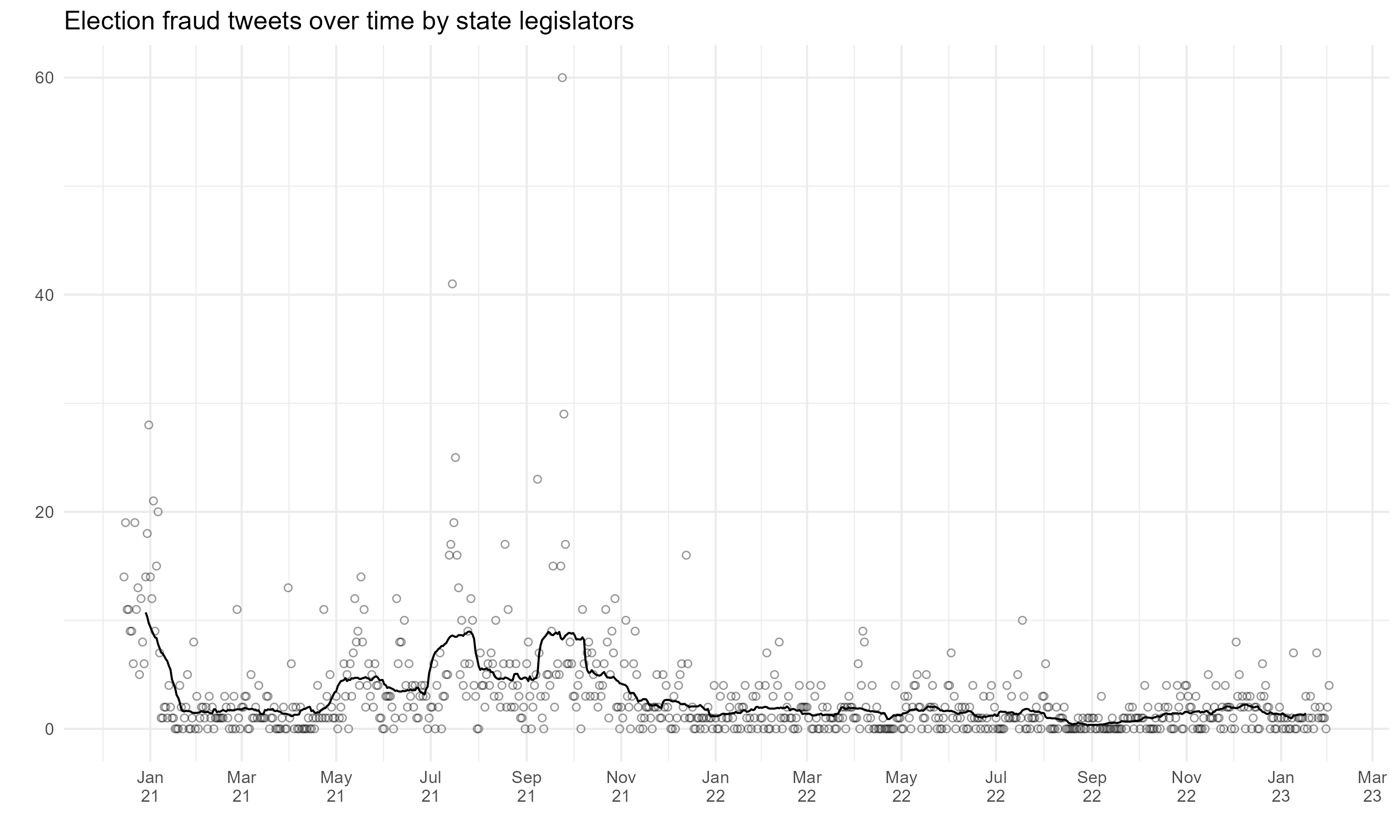

We first analyze the prevalence of election fraud tweets over time in the figure below, which reveals substantial variation. Unsurprisingly, we first see a flurry of activity in the aftermath of the 2020 election. Between December 15, 2020 and January 5, 2021, state legislators posted 284 tweets that endorsed claims of election fraud, an average of nearly 13 such tweets per day. A sharp break occurs after the storming of the Capitol on January 6th. Between January 7 and January 20, the day when Joe Biden was inaugurated as president, the rate drops to approximately 2 per day (a total of 26 tweets).

We observe little fraud claim activity during the rest of winter and spring 2021, but there are two noticeable peaks in July 2021 and September 2021. Manual inspection of the data makes clear that these are not random events. In mid-July, many of the tweets we categorize as endorsing election fraud claims refer to a segment presented on Tucker Carlson’s show on Fox News on July 14. On July 15, the Arizona State Senate held hearings on election fraud that also attracted commentary from state legislators. We can similarly account for the September 2021 spike: on September 24, the long-awaited forensic audit performed by the “Cyber Ninjas” in Maricopa County was made public.

Since then, there has been very little activity. Most notably, there was no observable spike in election fraud claims following the 2022 midterm elections in which Republicans took control of the House of Representatives but failed to gain a majority in the U.S. Senate (corresponding with public opinion trends after the election).

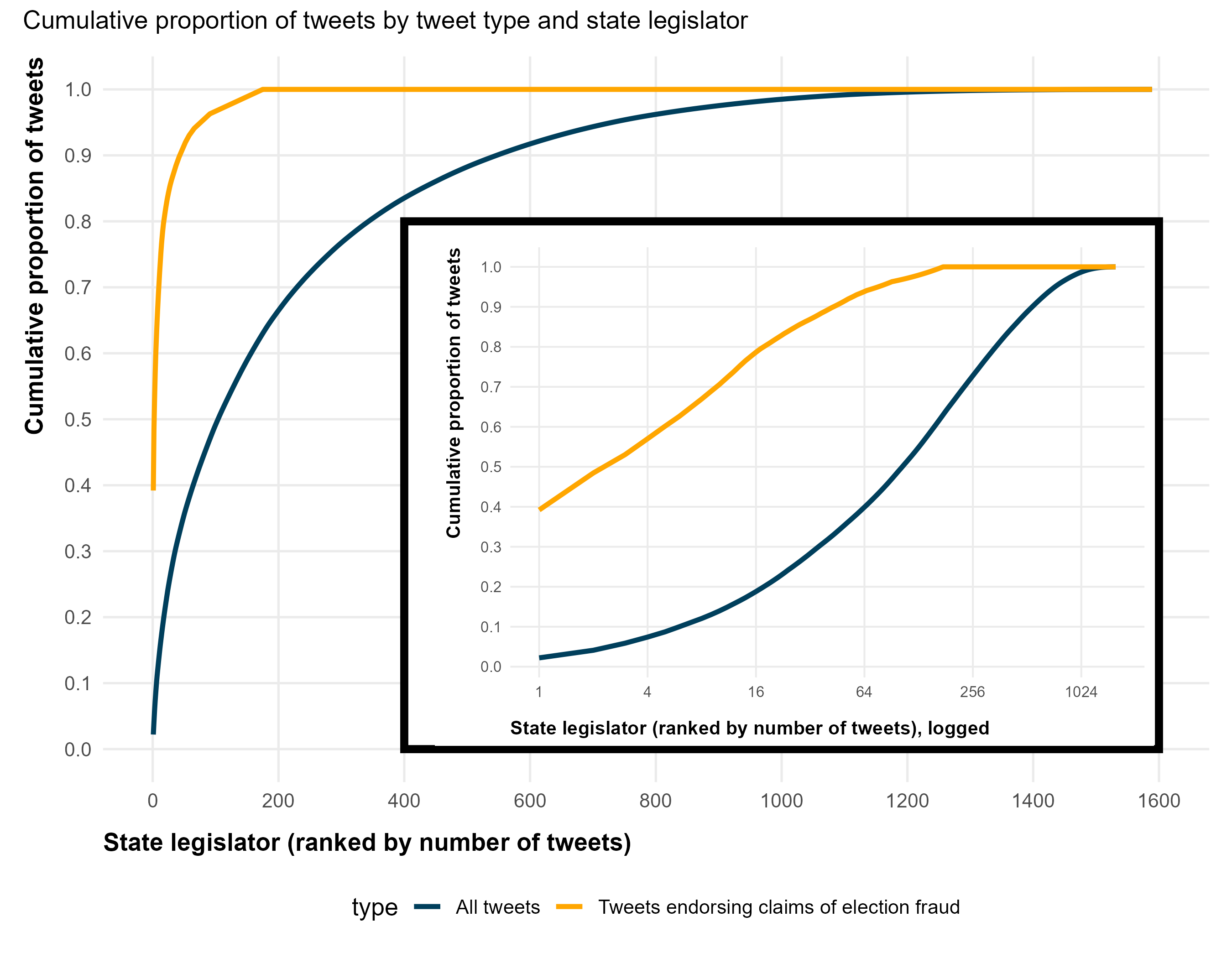

However, it is important to note that just a few state legislators are responsible for most of the problematic tweets that we identify. This pattern can be seen in the figure below, which shows the cumulative proportion of tweets as the x‑axis moves from the most prolific state legislator to the least prolific (separately for all tweets and for tweets endorsing claims of election fraud). As the figure shows, the supply of tweets is highly skewed in general: the most prolific Twitter users produce a disproportionate share of all tweets. However, the production of tweets that we classify as endorsing claims of election fraud is far more concentrated at the top.

Many of the most prolific fraud tweeters may be recognizable to avid news consumers. Most notably, Arizona state senator Wendy Rogers, a well-known defender of election fraud claims, appears 889 times in our data, which represents nearly 40% of all instances we identify. The next most prolific state lawmaker is Mark Finchem (210 tweets), a former member of Arizona House of Representatives who was the Republican nominee for Secretary of State in 2022. Doug Mastriano, the Republican nominee for Pennsylvania Governor in the same election cycle, is third with 110 tweets. Taken together, this trio accounts for more than half of all tweets that we identify as endorsing claims of election fraud. In total, we find qualifying tweets from 175 unique Twitter accounts belonging to 171 state legislators – approximately 4% of all Republican state lawmakers and 11% of those with an active Twitter presence.

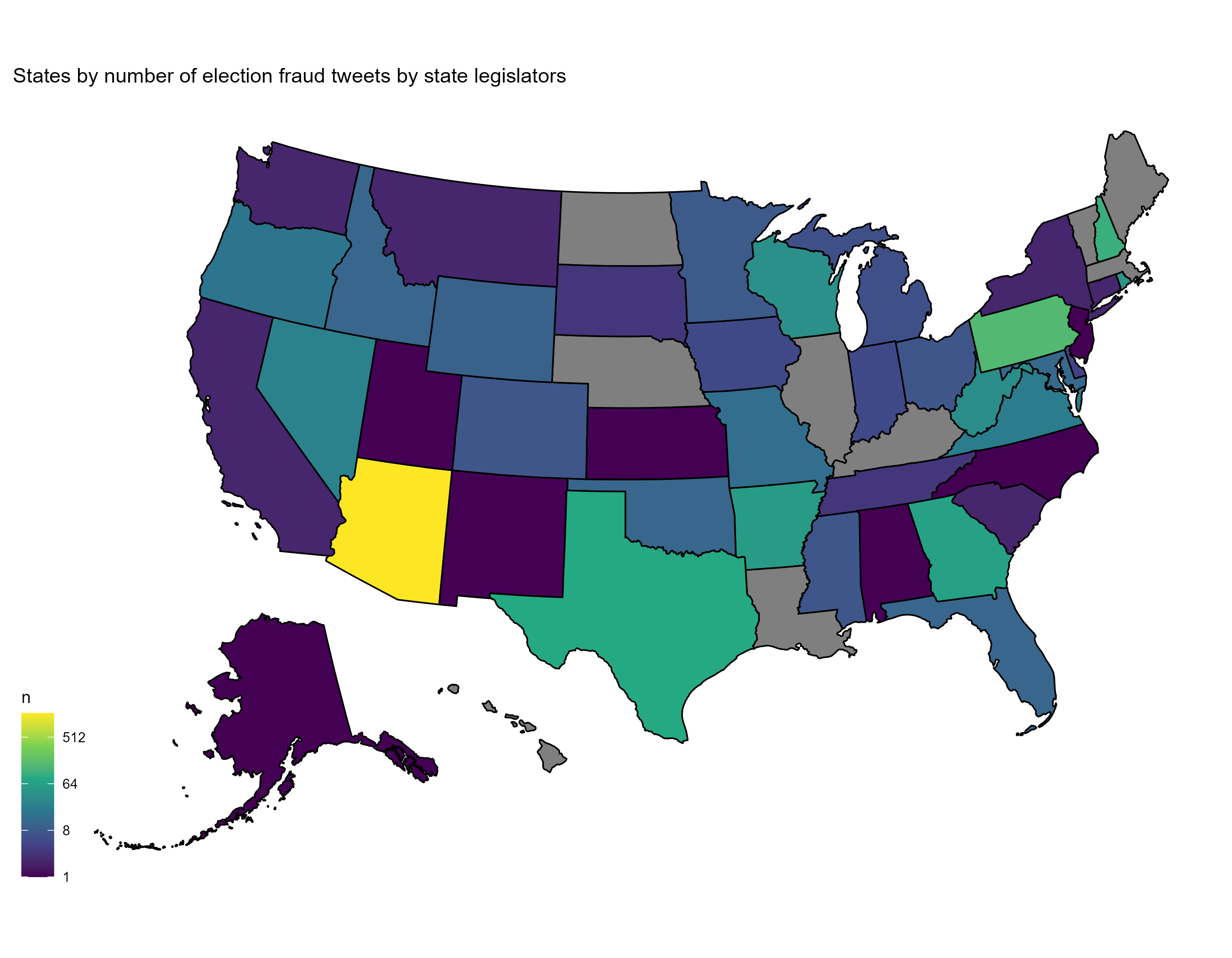

We find at least one qualifying fraud tweet from state legislators in 41 different states, but we also see huge variation across states driven by a handful of vocal election deniers. Most notably, Arizona stands out as the epicenter of election fraud discourse. Four of the five most prolific tweeters, and nine of the top sixteen, are from Arizona. Taken together, they account for approximately 66% of all fraud tweets we observe. Following Arizona, a handful of states are responsible for the majority of the remaining activity: we record 13 legislators producing 145 qualifying tweets in Pennsylvania, 11 legislators producing 101 tweets in New Hampshire, 18 legislators producing 82 tweets in Texas, and 17 legislators producing 39 tweets in Wisconsin.

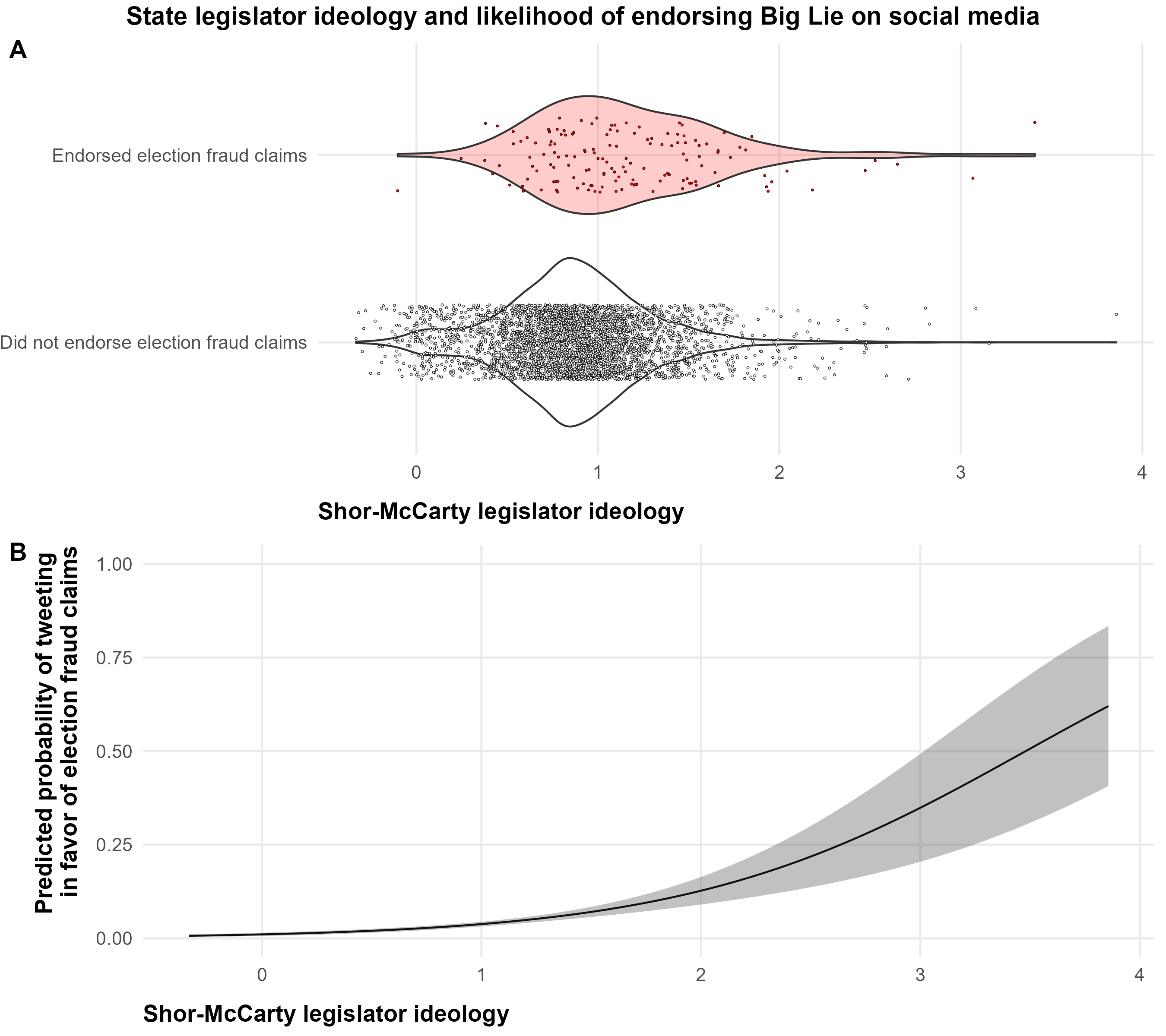

Are the legislators who endorse claims of election fraud ideologically extreme? We combined our data with estimates of state legislator ideology created by Boris Shor and Nolan McCarty These estimates, which were produced using a comprehensive record of roll call voting data over time in the 50 states combined with a recurring survey of state legislative candidates, are designed to be comparable across time, chambers, and states.

In panel A of the figure below, each dot represents a Republican state legislator. The dots in red at the top of the figure represent lawmakers who tweeted at least once in support of claims of election fraud, while the dots in black at the bottom show lawmakers who did not tweet in support of these claims. The mean Shor-McCarty ideology score of legislators who endorsed claims of election fraud is 1.18, compared to 0.88 for other legislators (higher values are more conservative). Panel B shows predicted probabilities of a Republican legislator endorsing claims of election fraud on Twitter as a function of Shor-McCarty scores (estimated using a logistic regression model). Among the least conservative Republican lawmakers, the estimated probability of endorsing claims of election fraud is essentially 0. At the 25th percentile of conservatism among Republican state legislators (an ideology score of approximately 0.65 in the Shor-McCarty data), the estimated probability remains low at about 0.02. The same is true for median ideology (the 50th percentile), where the estimated probability is 0.03. The estimated probability of endorsement only rises substantially at the most conservative end of the ideological spectrum, reaching 0.05 at an ideology score of 1.30 (87th percentile among Republicans) and 0.10 at an ideology score of 1.84 (98th percentile among Republicans).

However, it is not the case that legislators who endorse claims of election fraud are uniformly conservative. In fact, nearly 23% of the lawmakers that we identify as endorsing claims of election fraud have an ideal point that is less conservative than the GOP median. The least conservative lawmaker who posted at least one tweet endorsing claims of election fraud – Rhode Island state representative Michael Chippendale – is ranked at the 1st percentile of conservatism among all Republican legislators across the country.

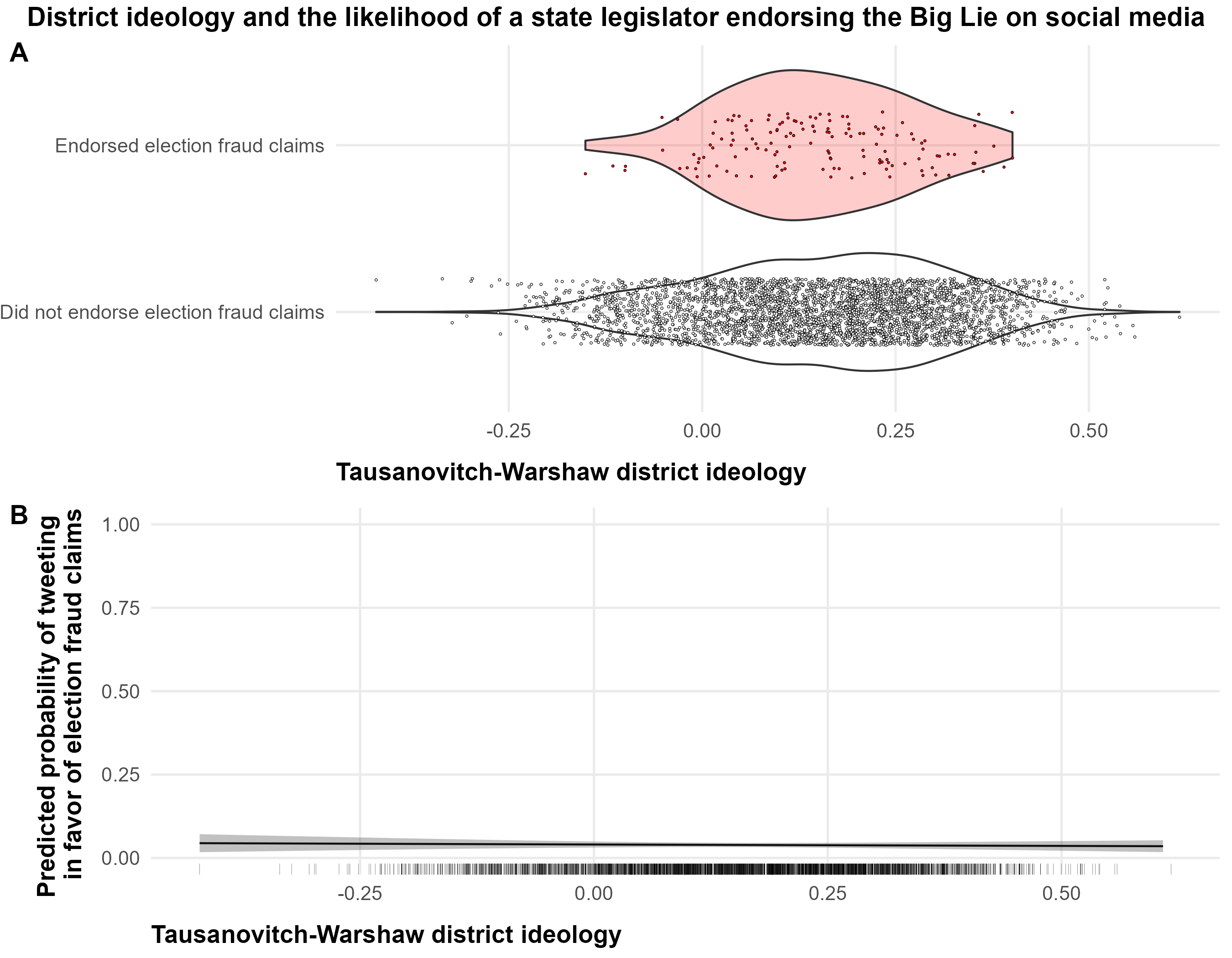

Strikingly, district ideology has even less predictive power. We repeated the procedure described above, but this time using a measure of public ideology in each state legislative district that was developed by Chris Tausanovitch and Christopher Warshaw1. Once again, each dot represents a Republican state legislator in panel A of the figure below. The dots in red at the top of the figure represent lawmakers who tweeted at least once in support of claims of election fraud, while the dots in black at the bottom show lawmakers who did not tweet in support of these claims. This time, the x‑axis shows the measure of public ideology for each state legislative district; higher values indicate policy preferences that are right-leaning, while lower values indicate policy preferences that are left-leaning.

In contrast to the findings related to legislator ideology, we find no clear discrepancy between the ideology of districts whose members did or did not endorse claims of election fraud. The mean district ideology in districts represented by legislators who endorsed claims of election fraud is approximately 0.154, while it is 0.148 for districts represented by legislators who did not (this difference is not statistically significant). Panel B of the figure reinforces this point: the predicted probability of a Republican state legislator endorsing election fraud claims on Twitter is essentially the same across the range of ideology in districts represented by Republicans.

This result should be interpreted carefully because our sample is restricted to Republican legislators, which necessarily restricts variation in district ideology. If we observed more Republican legislators in left-leaning districts, it is plausible that the relationship between district ideology and endorsement of election fraud claims would be stronger. In other words, we cannot claim that district ideology writ large has no observable link to legislators’ statements on election fraud. We can only say that, among Republican legislators, representing a strongly conservative district is not associated with a higher probability of endorsing claims of election fraud than representing a less conservative, or even a fairly liberal, district — a striking finding given the strong association between fraud endorsement and legislator ideology.

Appendix

-

We accessed the Ballotpedia page that lists the 99 state legislative chambers in the United States. Each chamber contains an embedded URL leading to its full Ballotpedia page. We scraped all 99 embedded URLs.

-

We used the Wayback Machine’s availability API to identify the latest archived version of a given state legislative chamber’s Ballotpedia page that preceded November 7th, 2022. On that date, most states held state legislative elections that substantially altered the composition of their legislative bodies. Since our project seeks to track behavior since December 2020, accessing archived versions of the Ballotpedia pages simplified the process.

-

We scraped all 99 archived versions of the Ballotpedia state legislative pages using the URLs provided by the Wayback Machine’s availability API. Each page contained a table of current members, along with embedded URLs to each member’s Ballotpedia page. We extracted this information from each page, which resulted in a dataset of 7,383 state legislators.

-

We scraped the Ballotpedia pages of all 7,383 legislators. In the vast majority of cases, a legislator’s page contains an information box with basic biographical information (name, office, party, etc.) as well as a list of social media accounts.

-

A minority of state legislative seats had not been held by the same individual since December 2020. There were two broad categories of such cases: (i) a seat that was listed as empty, and (ii) a seat whose current holder assumed office after December 2020.

-

In the latter case, we accessed the current officeholder’s Ballotpedia page and extracted information on their predecessor (which was usually contained in the infobox at the top-right of the page or in a box at the bottom of the page).

-

In the former case (empty seat) or whenever the above method did not yield information on a predecessor, we queried the Wayback Machine’s accessibility API to find an archived version of the Ballotpedia page of their state legislative chamber, with a target date 180 days before the current officeholder took office.

-

We then scraped this archived version of the Ballotpedia state legislative chamber page, extracted the table of then-current members, located the relevant legislative seat, and extracted information on the then-officeholder (if any). Using the Twitter API, we scraped all tweets from the Twitter accounts of Republican state legislators identified above between December 2020 and January 2023.

-

-

For each legislator identified through the process described above, we scrape their Ballotpedia page and store information on their social media accounts.

-

We used keyword searches to flag tweets that could endorse claims of election fraud. Keywords such as “dead people vot,” “illegal vot,” “rigged elect,” and “steal elect” were among those used to identify tweets related to election fraud narratives. Additionally, co-occurring keyword pairs like “vot” and “fraud” or “elect” and “integrity” were detected to enhance precision. The criterion used to flag tweets can be found here.

Undergraduate research assistants consulted each tweet identified through the above process and determined whether or not each tweet should be classified as endorsing claims of election fraud. The full codebook that research assistants referred to can be found here. Tweets that met any of the following criteria were classified as endorsing claims of election fraud:

-

Claims that there was fraud in the 2020 or 2022 elections, unless the tweet specifies that such fraud was extremely rare.

-

Calls for, endorsements of, or updates on non-routine election audits.

-

Statements that question the veracity of claims made by election authorities regarding the legitimacy of elections.

-

Claims that the outcome of the 2020 election is unknown.

-

Usage of dubious evidence to support claims of electoral fraud.

Tweets that met the following criteria were not classified as endorsing claims of election fraud (unless they also met one of the above criteria):

-

Statements about “election integrity” that do not include specific claims regarding the 2020 or 2022 elections.

-

References to routine audits (e.g., audits triggered automatically because of narrow margin).

-

Calls for future audits.

-

Statements decrying a federal takeover of elections.

Each tweet was coded by at least two research assistants. Tweets for which coders made different decisions were then assigned to a third coder as a tiebreaker. For the final data, Cohen’s kappa is 0.70, indicating fairly good consistency in coding decisions across research assistants.