BLW conducted its first U.S. Democracy Survey from February 13–19, 2017. We invited 9,820 political science faculty at 511 U.S. institutions to participate and received 1,571 responses (a response rate of 16 percent).

The set of invitees was constructed from the list of U.S. institutions represented in the online program of the 2016 meeting of the American Political Science Association conference. We then collected email addresses for regular, adjunct, and emeritus faculty from the political science departments at each of these institutions.

Survey design and rationale

The survey had two broad goals. The first was to learn what qualities our respondents regard as most essential to democracy. Democracy is a complex, contested concept whose definition has been debated for centuries. We wanted to know which characteristics professional political scientists regard as the most important for democracy and which elements they regard as less essential. Our second purpose was to use that same set of characteristics to assess how our respondents rate the current state of democracy in the United States.

At the core of the survey were two batteries of questions organized around the following nineteen statements:

- Elections are conducted, ballots counted, and winners determined without pervasive fraud or manipulation.

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in unpopular speech or expression.

- Government agencies are not used to monitor, attack, or punish political opponents.

- Government does not interfere with journalists or news organizations.

- All citizens have equal opportunity to vote.

- All citizens enjoy the same legal and political rights.

- The elected branches respect judicial independence.

- Executive authority cannot be expanded beyond constitutional limits.

- Government effectively prevents private actors from engaging in politically motivated violence or intimidation.

- Parties and candidates are not barred due to their political beliefs and ideologies.

- Government officials are legally sanctioned for misconduct.

- The judiciary is able to effectively limit executive power.

- The legislature is able to effectively limit executive power.

- Elections are free from foreign influence.

- Government officials do not use public office for private gain.

- All votes have equal impact on election outcomes.

- In the elected branches, majorities act with restraint and reciprocity.

- Government leaders recognize the validity of bureaucratic or scientific consensus about matters of public policy,

- Political competition occurs without criticism of opponents’ loyalty or patriotism.

In the first battery, participants were asked, “How important are these characteristics for democratic government?” They rated each of the nineteen statements on the following scale:

- Not relevant. This has no impact on democracy.

- Beneficial. This enhances democracy, but is not required for democracy.

- Important. If this is absent, democracy is compromised.

- Essential. A country cannot be considered democratic without this.

The second battery asked, “How well do the following statements describe the United States as of today?” Each respondent was then asked to rate the same nineteen statements using the following response options:

- The U.S. does not meet this standard.

- The U.S. partly meets this standard.

- The U.S. mostly meets this standard.

- The U.S. fully meets this standard.

- Not sure.

The order in which statements were presented in each battery was randomized for each respondent so there should be no priming or ordering effects in how they were assessed.

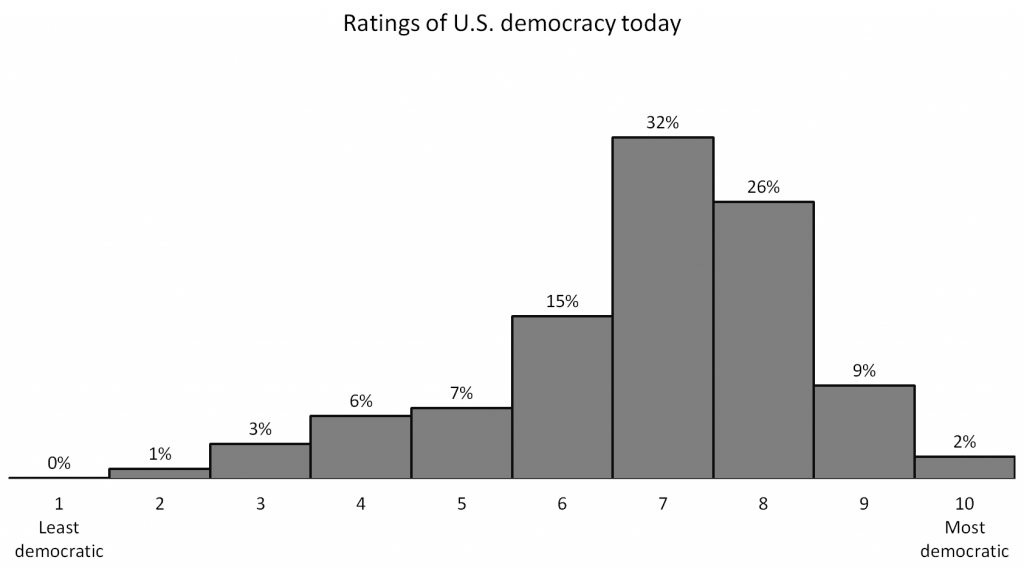

After these two extensive batteries, we asked respondents to rate democracy in the United States today on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 is least democratic and 10 is most democratic.

In developing this list, we attempted to capture a range of characteristics that are prominent in both minimalist and expansive definitions of democracy. The statements describe both institutions and practices, including elections, citizens’ rights, checks on political authority, mechanisms of accountability, and behavioral norms.

Of course, our list of attributes is not comprehensive. However, it includes many — though certainly not all — of the institutional characteristics that foster competition and participation. As such, it arguably speaks more to electoral and liberal conceptions of democracy, such as the institutional guarantees outlined in Robert Dahl’s seminal work or the Madisonian vision of limited government, than to more deliberative or majoritarian conceptions. We also tried to select attributes that are central to public debate about the status of contemporary democracy in the U.S. Again, however, the list is necessarily incomplete. It does not include, for instance, questions about party strength, campaign finance, turnout, or political engagement.

Findings

What matters for democracy

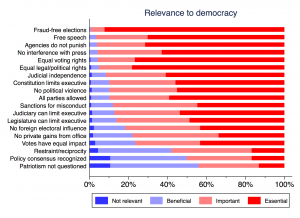

The figure below shows the distribution of responses on the importance to democracy battery for each of the statements. The statements are ordered from top to bottom on the y‑axis by the proportion of responses that deem a principle important or essential to democracy. (Summary statistics in tabular form are here.)

Respondents regarded some characteristics of elections as far more central to democracy than others. Although political scientists regularly warn against simply equating elections with democracy, they overwhelmingly rated elections that are free of widespread fraud and manipulation as the most important single element of democracy among the nineteen on our list. Fully 92% of respondents rate elections without widespread fraud as essential, which is far higher than for any other principle, and another 7% regard them as important.

Besides clean elections, respondents identify a series of characteristics related to basic individual rights as highly important, including free speech (#2), equal access to the vote (#5), and equal political and legal rights for all citizens (#6).

Also toward the top of the list is a group of characteristics that focus on safeguards for political opposition and dissent: no surveillance and harassment by government agencies (#3), a free press (#4), government protection against private political violence (#9), and guarantees for parties to compete regardless of ideology (#10).

A group of items in the middle of the distribution pertain to mechanisms of accountability: judicial independence (#7), restraints on the expansion of executive power (#8), guarantees that misconduct by public officials will be sanctioned (#11), the ability of the judiciary (#12) and the legislature (#13) to check executive authority, and that government officials do not use public office for private gain (#15).

Nearer to the bottom are two characteristics of elections that have been controversial of late in the United States — that they should be free from foreign influence (#14) and that all votes should have equal impact on election outcomes (#16). The contrast with respondents’ emphasis on elections free of fraud (#1) and equal voting rights (#3) is noteworthy. Perhaps reflecting the knowledge that there is no neutral way to aggregate preferences, the responses to our survey display a sharp disjuncture between insistence on equality in citizens’ right to vote and the level of importance given to those votes having equal impact.

Clustered at the end of the list are some behavioral norms that are not codified in statutes or the Constitution, but that have been the subject of discussion in the past year — that elected majorities should act according to norms of restraint and reciprocity (#17), that politicians should campaign without disparaging their opponent’s patriotism or loyalty (#18), and that public officials should recognize scientific or bureaucratic consensus (#19). It is important to note that roughly 90% of respondents still ranked such norms as at least beneficial to democracy.

Performance of democracy in the United States

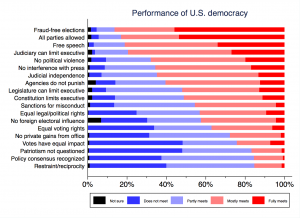

Shifting from theory to practice, we now present the distribution of responses on the battery assessing U.S. democracy today. The statements are again ordered vertically according to the combined share of responses indicating that the United States fully or mostly meets the standard (as opposed to partly or not at all). (Summary statistics in tabular form are here.)

The picture here is mixed. On only 10 of the 19 attributes did half or more of all respondents judge the United States to mostly or fully meet the standard in question. At the high end, 86% said the country mostly or fully meets the standard that elections are free from widespread fraud and manipulation. Likewise, the U.S. performs quite well in terms of open party competition, protecting free expression and media, judicial independence and checks on executive authority, and protection from private political violence and government harassment. By contrast, respondents gave relatively low marks to the U.S. on the remaining characteristics. For example, more than half of the political scientists surveyed estimated that the U.S. does not meet or only partly meets the standard that elections are free from foreign influence. Similarly, more than two-thirds said that the U.S. did not meet the standard of government officials refraining from using public office for private gain and votes having equal impact. And more than three-quarters responded negatively to U.S. performance on basic norms of debate and deliberation.

Comparing importance to democracy with U.S. performance

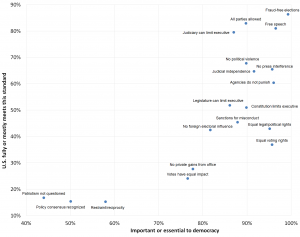

It is especially interesting to consider how political scientists rank the U.S. in terms of the characteristics that they regard as especially important to democracy. This relationship is captured in the figure below, which plots the combined share of responses that rate the U.S. as fully or mostly meeting each standard against the share of responses that rate a principle as essential and important to democracy.

There is a clear positive correlation between assessments of importance to democracy and perceived US performance. Perhaps most reassuringly, respondents rate the U.S. highest on the characteristic they view as most essential to democracy — clean elections. The contrast with President Trump’s narrative of rampant voter fraud is stark on this count. Using data from the 2016 election and prior contests, scholars have closely examined claims that voter fraud is widespread and have consistently found no evidence to substantiate them. Political science faculty at large appear to have accepted these findings and accordingly rate U.S. elections highly. The U.S. also fares well on other important dimensions ranging from party competition and free speech to the judiciary’s check on the executive and limiting private political violence.

There are, nevertheless, multiple important attributes on which half or more of respondents regarded the U.S. to be falling far short of democratic standards. Most notably, respondents rate the U.S. relatively low on the qualities held to be second- and third-most important for democracy — equal legal and political rights and equal voting rights for all citizens. These evaluations likely reflect concerns about racial disparities in the application of criminal law and the potentially disparate effects of voter registration and identification laws and changes to voting procedures on minority voters.

The United States rated even lower on some norms of behavior that, although less critical, are still regarded as either essential or important to democracy by around half of our respondents. On the statements about civil political discourse, majority restraint, and deference to non-political sources of information, more than 80% regarded the United States as failing. Some prominent observers (here and here) regard erosion of behavioral norms along these lines as an early warning sign of democratic backsliding.

Overall rating

The next figure shows how respondents rated democracy in the United States on a 1–10 scale (where 1 is least democratic and 10 is most democratic). The responses skewed toward the favorable end of the rating scale. Almost seven in 10 respondents (69%) rated the U.S. at 7 or better and 36% at 8 or better, while only 1 in 6 respondents rated it at 5 or below.

We are hesitant, for now, to interpret these scores without points of comparison both across time and cross-nationally. We hope to provide such comparisons in future work. At this point, though, it fair to conclude that expert opinion among political scientists views the state of democracy in the U.S. relatively favorably, though they also recognize some serious flaws.

Conclusion

These findings provide mixed news. Despite an atmosphere of pessimism or panic among many observers and public intellectuals, the political science community holds a rather nuanced view of democratic governance in the United States as of February 2017. They rate the U.S. as performing well on many of the criteria that they say are most important for democracy. For instance, 86% say the United States fully or mostly meets the standard that elections are free and fair and approximately 80% say the same for the standards of protecting free speech and the judiciary limiting executive power.

The results, however, also provide significant reason for concern. Fewer than two-thirds (66%) are as confident that journalists can operate unimpeded by the state, that the elected branches respect judicial independence (65%), or that government agencies are not used to monitor and harass political opponents (60%). Only the barest majorities are confident that Congress can effectively check the executive or that executive authority can be constrained within constitutional limits (52% and 51%, respectively).

With regard to equal rights, both in voting and more generally, our respondents assess U.S. performance even more dismally, probably reflecting long-standing institutions of electoral exclusion and wide socioeconomic inequalities that have been matters of concern for many years. Finally, respondents’ evaluations of basic behavioral norms related to civil discourse, reciprocity, and the recognition of common standards of facts and analysis rate worst of all.

Ultimately, these findings provide an essential baseline measure of how political science experts view the status of American democracy in early 2017. As part of our continued effort to track what a wide range of professional political scientists think about democracy in contemporary America, we welcome input on these surveys going forward. We plan to conduct additional waves of the survey each quarter that will include new questions and comparisons with other time periods and other parts of the world. We invite critical feedback on our initial design and also encourage colleagues to use the data from our survey to examine our results further. In all of these ways, we hope to foster informed debate among our profession and in the country at large about the health of American democracy.

Appendix: Critical Evaluation of the First Bright Line Watch U.S. Democracy Survey

Our goals in designing the BLW U.S. Democracy Survey were to measure which characteristics our respondents regard as most critical to democracy and to assess the performance of democracy in the United States and elsewhere against that set of ideals.

Creating a survey instrument that can fulfill all of these goals proved to be a challenging task. We recognize and appreciate the comments we have received so far and welcome further feedback. To explain the motivation for the survey design, we offer some observations here about the choices we made in the process. (We also welcome comments on our analysis of the survey data, which we have made available online.)

Distinguishing the most essential characteristics of democracy

We first wish to report that our efforts to design a survey that allowed respondents to make distinctions among different characteristics of democracy appears to have been successful.

For this survey to provide useful results, it was important that respondents did not simply equate democracy with every normatively desirable characteristic of politics and government. If they had simply rated each characteristic as essential, the survey would have provided no information about their relative importance.

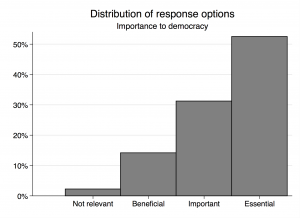

The histogram below shows the distribution of all responses on the importance to democracy scale across all nineteen statements:

Respondents effectively used three of the four response options and those answers skewed toward the highest scale value. However, the distribution of responses varied tremendously at the statement level. Consider the first bar graph showing the distributions of responses for each statement about importance to democracy. The combined share of responses indicating that a given principle is either important or essential runs from 99% for clean elections to below 50% for respecting political opponents. The proportion of respondents rating a characteristic as essential varies even further (11% to 92%). We find these results reassuring. They suggest that respondents regarded our statements as relevant to democracy, but sharply distinguished among them in terms of their relative priority.

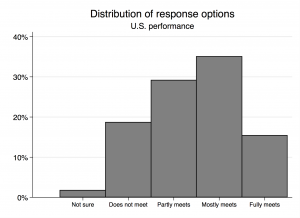

The next figure shows the corresponding distribution of responses on the U.S. democracy battery. Reassuringly, respondents used the whole scale in rating the performance of the U.S. The distributions of responses also varied dramatically across the statements.

In the second bar graph, showing the distributions of responses for each statement with respect to US performance, note in particular the discrepancies between the shares of “Fully meets this standard” (red) and “Mostly meets this standard” (pink). We expected many respondents to be reluctant to render a judgment of full compliance with almost any standard. (After all, there are are always deviations from democratic ideals.) We therefore regarded the combined share of “Fully meets” and “Mostly meets” responses to be particularly informative in showing that respondents were discriminating between statements.

Political bias

Some of the critical responses to the survey ran along the lines of:

- “Seems driven by a political agenda.”

- “Given the timing of the request, it’s easy to assume that you aim to characterize the political science profession as believing the Trump administration to be a threat to American democratic institutions.”

First, our aim with the first survey was to assess how political scientists define democracy and how they rate its performance in the United States. In subsequent surveys, we plan to ask respondents to assess U.S. democracy in other time periods and to assess democracy in other countries. In other words, we sought to design the survey to be flexible and generalizable. In crafting the statements in our batteries, we sought to reflect principles that are salient cross-nationally and across time periods. The first survey establishes some baseline results that will be useful for comparisons going forward.

It would be disingenuous, however, not to acknowledge that our own level of interest in these issues was elevated by recent events in the United States. The election that brought Donald Trump to the presidency was unprecedented in recent history in numerous respects. Many of the actions and behaviors for which Trump is criticized are reflected in the statements included on our survey. Furthermore, political science faculty, like the professoriate more generally, tend to identify with the Democratic Party and a number of political scientists have published commentary (here, here, and here) arguing that the Trump presidency represents a threat to American democracy.

With all that in mind, we note that, if respondents were engaging with our survey as a vehicle to bash President Trump, we would expect them to prioritize the statements that most closely reflect the actions on which Trump has been most widely criticized:

- Attacking Clinton’s character during the campaign;

- Making factual claims contradicted by authoritative sources;

- Failing to separate his private financial interests from official business;

- Inviting foreign influence over the U.S. election.

Respondents did rate the U.S. low on the statements most closely related to those controversies, but they also ranked these characteristics among the least important to democracy (#19, #18, #15, and #14, respectively). These results suggest that respondents were not merely using the survey as a vehicle for anti-Trump venting, which is welcome news.

Summing up

There is certainly more to say about the first BLW survey. We will monitor feedback carefully and invite thoughtful criticisms of the survey, particularly those that suggest ways to improve going forward. We are open to publishing such contributions on this blog in an effort to generate a sustained discussion about how best to evaluate what matters to democracy and how to measure it in practice.

For now, we are gratified with our initial survey on a number of counts. First and foremost, we appreciate that so many of our colleagues were willing to take the time to offer their views and expertise. Second, the statements we included in our batteries appeared to resonate with respondents, but also allowed them to distinguish principles according to importance. We think these results tell us quite a bit about which characteristics political scientists regard as central to democracy and which they regard as more peripheral. Finally, our respondents appear to have answered these questions in a relatively dispassionate manner. At the least, they did not appear to engage in reflexive expressions of dismay at the new administration — an encouraging sign for the validity of this new research enterprise.

The percentage of respondents is way too low, even though the the relevance of the evaluating criteria is very good. Maybe a followup aiming at a more robust response rate seems to be in order.

I appreciate this work very much, especially how it teased out many facets of a functioning democracy. I am very concerned about the response rate, as 16% is not representative of anyone or anything. A demographic analysis of respondents would be interesting, and I want to know who is missing eg a nonresponse analysis. It is vital to increase the numbers to keep this survey relevant going forward. That said, great work!

I, too, salute your important initiative, and am about to studyour initial survey in detail.

However, beforengaging in the substance I must echo Batestrom’s concern over the { somewhat ? } { very ? } { extremely ? } low response rate :

for if it is so that ” … 16% is not representative of anyone or anything … ” then with what authority can the survey speak ?

Further, per Batestrom, a demographic analysis of respondents, as well as a nonresponse analysis, would be most illuminating :

what kind of response rate assures greater credibility by representing a ’ true ’ national consensus ?

Finally, per Batestrom, the work is indeed to be complimented, regardless of the initial disappointment :

perhaps more response time is in order ?

I, too, read of your study in The Washington Post. Thank you for providing a data-driven source of information in this climate of emotionally charged rhetoric. I look forward to following your work as these troubled times unfold.

I am so excited! I just read about your site in the Washington Post. What you’re doing is incredibly valuable because our American democracy is very much at risk with the Trump administration. I am creating a course “But Can It Happen Here?” based on the book by Sinclair Lewis “It Can’t Happen Here.” It’s scheduled for summer session at Yavapai College’s Osher Lifelong Learning Program (OLLI) in Sedona, Arizona. Right now the president of the League of Women Voters is facilitating back-to-back classes on “Healing the Heart of Democracy” (Parker J. Palmer). Our class this term is quite fearful about Trump. My class will follow these two classes. While I have a stack of books I’m reading, I always welcome suggestions for books to read. Thank you for your new site; it could help save our democracy.

This is a vitally-important survey, and continuing to re-run it longitudinally in the future will give us more confidence in the results. Hopefully, you will have a higher response rate in the future. In addition, I think you do need to include questions about public financing of campaigns/campaign-finance reform, and the re-districting process (gerrymandering) in your list of “essential” attributes. Without these rules, it is conceivable that U.S. democracy may reach a tipping point towards violence as the vast majority of the voiceless and powerless reject Madisonian norms. Still, great job, and thank you.

Van Doorn affirms the <> procedural concerns, supra :

continue to re-run the survey longitudinally in the future in order to bolster credibility and authority ;

a higher response rate is essential.

{ Expanding question base to include both campaign finance and districting issues as essential attributes is an excellent suggestion ! }

I appreciate the work you have done here. It will be interesting to see how these responses may change or not change over time as political conditions vary.