The Health of American Democracy:

Comparing Perceptions of Experts and the American Public

Bright Line Watch

October 5, 2017

Given widespread concern about the possible erosion of democracy in the United States, Bright Line Watch has conducted expert surveys since early 2017 asking thousands of professional political scientists to identify the dimensions of democracy they see as most important and to rate how well the U.S. is performing on them. But does the public agree with those assessments?

This Bright Line Watch report summarizes our third survey on the state of democracy in the United States. Uniquely, this round directly compares results from parallel surveys of our expert sample of professional political scientists and a representative sample of the American public recruited from the YouGov online survey panel.

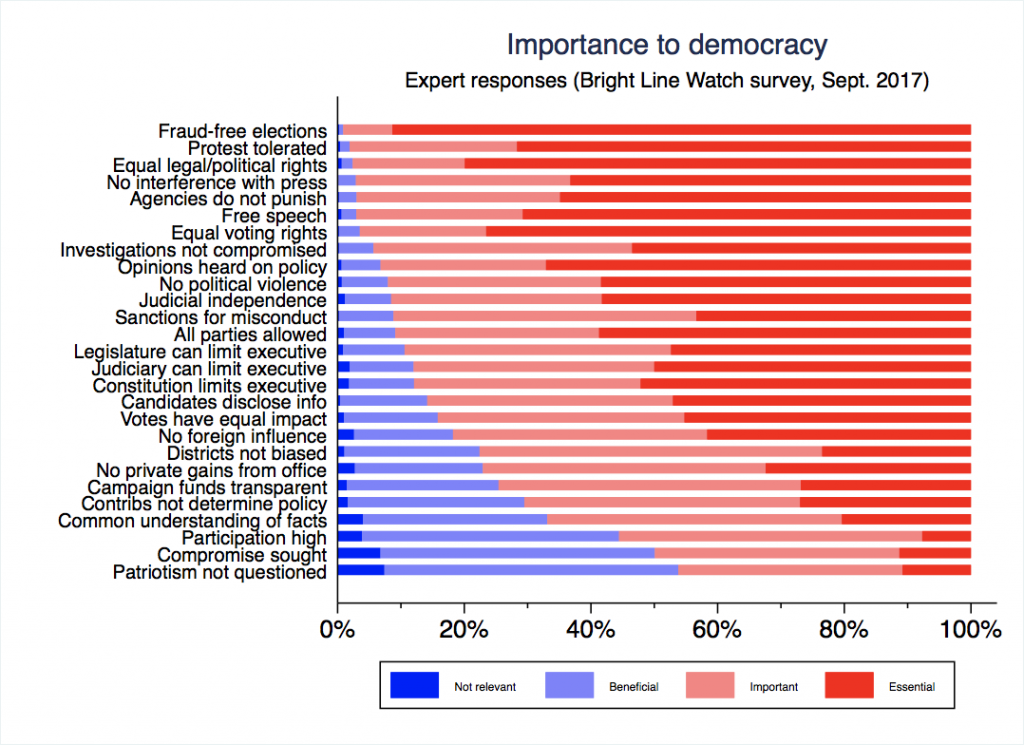

In our expert surveys, including the most recent one, political scientists have drawn sharp distinctions between dimensions that are crucial to democracy such as clean and inclusive elections and others that they see as less crucial such as a common understanding of facts.

The good news is that on these most important dimensions, the experts see American democracy as performing well. Elections are basically fraud free, in their view, and rights of association are respected. On some other dimensions, the performance of U.S. democracy is weaker, but these are often aspects of democracy that experts view as less important. Politicians frequently impugn their opponents’ patriotism, for instance, but American democracy is not directly threatened by this lack of rhetorical restraint.

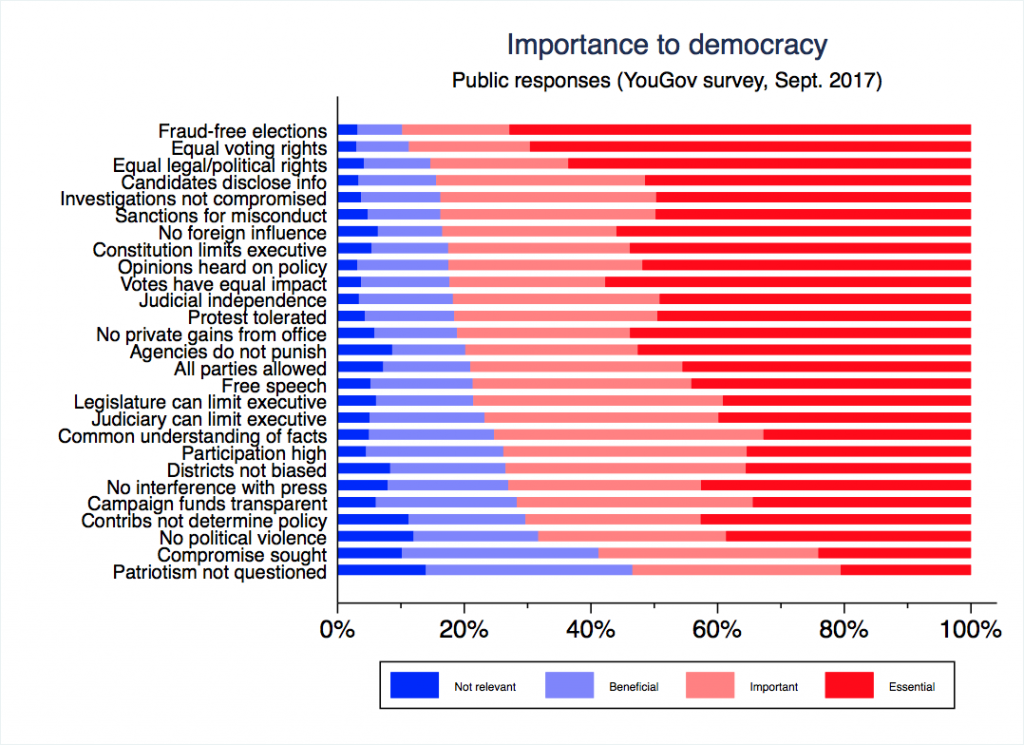

To probe the public’s views of the health of U.S. democracy, we asked a representative sample of 3,000 American adults the same questions that we asked our expert sample (details on our surveys are provided below; both were conducted September 9–18, 2017). What are the most important dimensions of democracy and how is the U.S. performing on them?

The sensitivity of common citizens to threats to democracy is important. The concept of a “bright line” for democracy (from which our organization takes it name) suggests that some violations of institutions and norms will be so self-evident and egregious that common people will reject them. If we found out the public was complacent about threats to democratic institutions and norms, it would be a cause for concern.

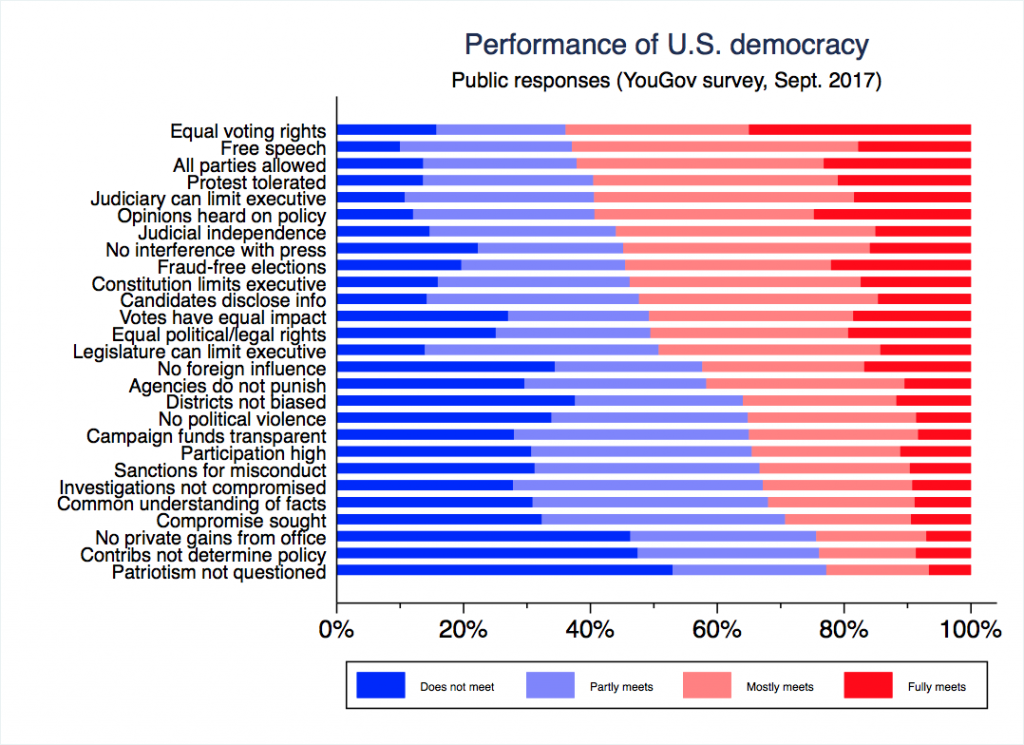

However, we find the opposite. The public is quite concerned about the state of U.S. democracy, especially those who disapprove of President Trump. Americans’ ratings of democratic performance are often worse than those of experts, especially in the areas experts identify as the most important. In general, experts seem to have a less negative view of how well U.S. democracy is doing than the public. We summarize the key findings from our data below.

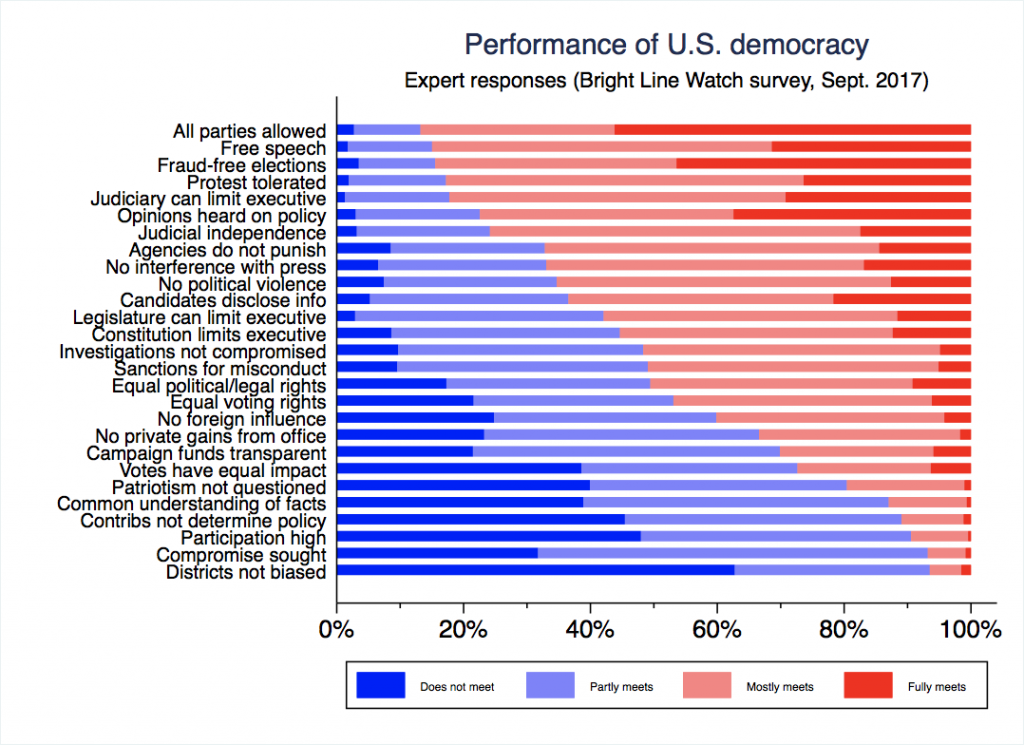

The public is more discouraged about American democracy than the experts

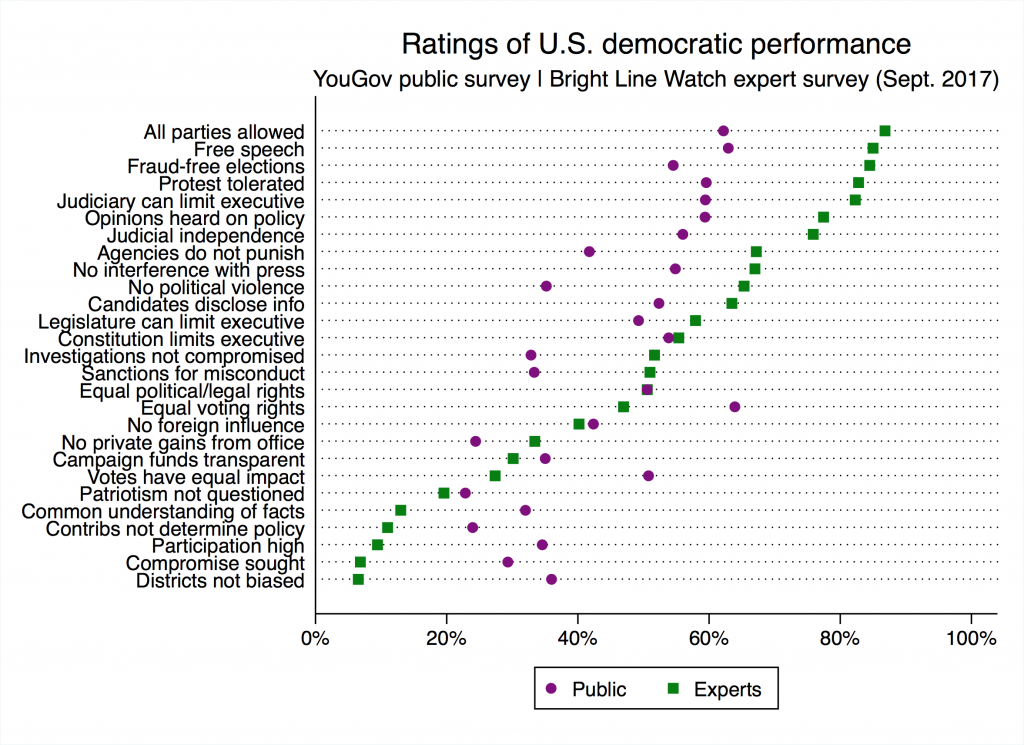

Far from being complacent, the American public is in many ways more alarmed than political scientists are about the health of U.S. democracy. They are, for instance, less sanguine about the administration of elections and about protections for free speech and less certain that political parties can compete freely and that people’s rights to protest are protected. On 27 dimensions of democratic performance that we asked respondents to consider, experts offered more positive evaluations than the public did on 16. Other dimensions on which this was true include freedom of the press, the ability of citizen to make their opinions heard, the political neutrality of government agencies, and protections against political violence. (See Figure 1.)

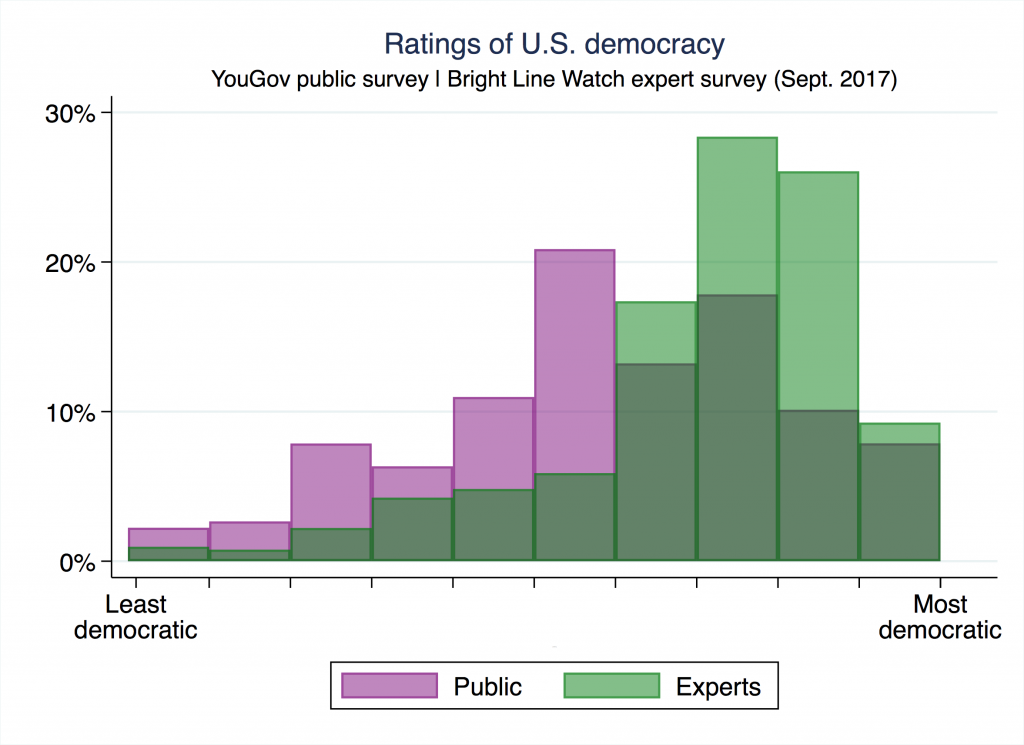

The experts assessed U.S. democracy more positively than the public not only on an item-by-item basis but overall as well. After they had assessed the distinct dimensions of democracy, we asked both the experts and the public to rate U.S democracy overall. On a 100-point thermometer scale, with higher scores reflecting more positive evaluations, the median rating of experts was 72 compared to 59 among the public. (See Figure 2.)

The public’s greater skepticism did not extend to all dimensions of democratic performance. They were less discouraged than experts about matters of electoral fairness and worry less about electoral districts being biased, votes having an unequal impact on outcomes, large donors determining electoral outcomes, and participation rates being low. On all these counts, we suspect that the broader familiarity among experts with international standards might account for their relative pessimism. Most other democracies have in place electoral rules that produce clearly better results on these items. The other set of statements on which the experts rate U.S. performance lower than the public relates to discourse and behavioral norms: seeking compromise, maintaining a common understanding of facts, and not questioning the loyalties and integrity of political opponents.

Trump supporters and opponents share common democratic principles

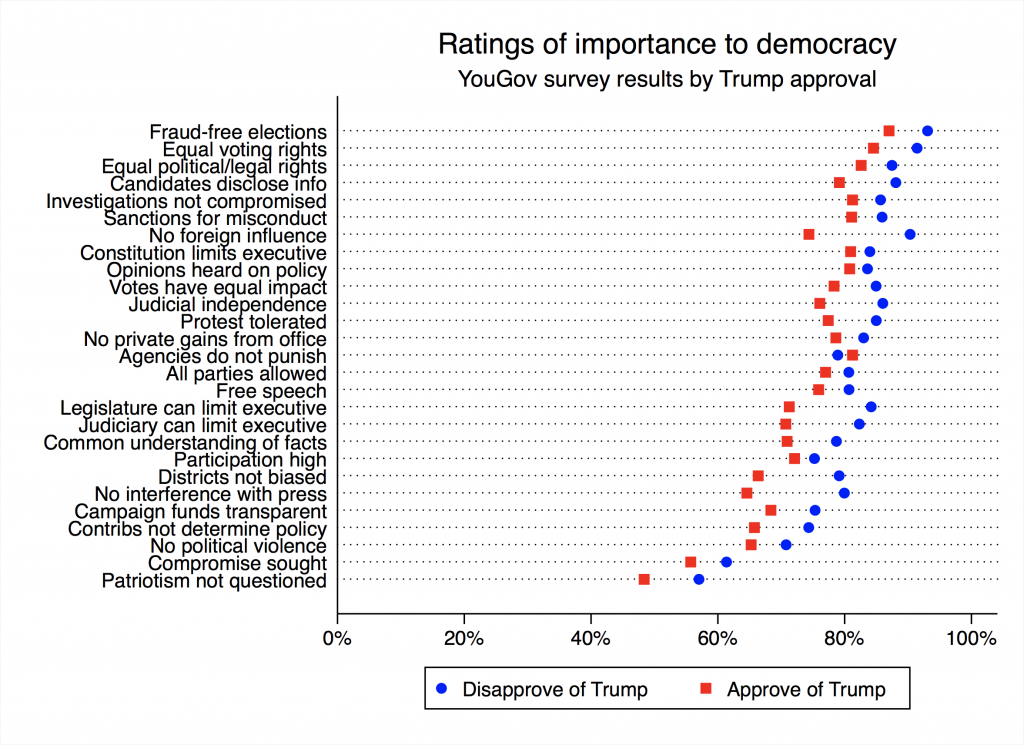

Given the sharp divergence seen between supporters and opponents of President Trump in many domains, we were interested to see whether this polarization extended to their opinions about the importance of various aspects of democracy. Figure 3 below separates respondents by whether they approve (strongly or somewhat) and those who disapprove (strongly or somewhat) of President Trump’s job performance. For respondents in each group, the respective markers indicate the percentage who rate each statement of principle to be either essential or important to democracy. The statements are listed in descending order of overall importance (that is, the total percentage of Americans who rate it as essential or important in the population as a whole).

Trump’s backers and detractors often have quite similar views on which dimensions of democracy matter most. Both groups rated clean elections, politically neutral investigations of public officials, and equal legal, political, and voting rights as most important for democracy. Both groups also rated norms of discourse, such as seeking compromise with one’s political opponents and not calling their patriotism into question, as least important. The rough parallelism in importance ratings across the range of statements suggests that what Trump supporters and opponents value in democracy is not entirely antithetical.

There are some intriguing differences, however. With only one exception (“Government agencies are not used to monitor, attack, or punish political opponents”), those who disapprove of Trump rate each principle as more important to democracy than those who approve. Relatively speaking, Trump supporters are preoccupied with the political neutrality of government agencies even while their champion heads the executive branch. This finding may indicate their embrace of the “deep state” narrative, according to which executive branch agencies are responsive to politically motivated directives from sources other than (and hostile to) the White House.

Figure 3 also highlights the democratic principles on which values diverge most between Trump supporters and opponents, which is indicated by the horizontal space between points. We observe the greatest polarization on the following principles:

- “Elections are free from foreign influence”

- “Government does not interfere with journalists or news organizations”

- “The legislature is able to effectively limit executive power”

- “The judiciary is able to effectively limit executive power”

All of these are rated as more important by Trump opponents than his supporters. The reasons seem straightforward — many of the president’s supporters likely share his confrontational posture toward the news media, while Trump skeptics are more concerned with checking executive authority and foreign influence.

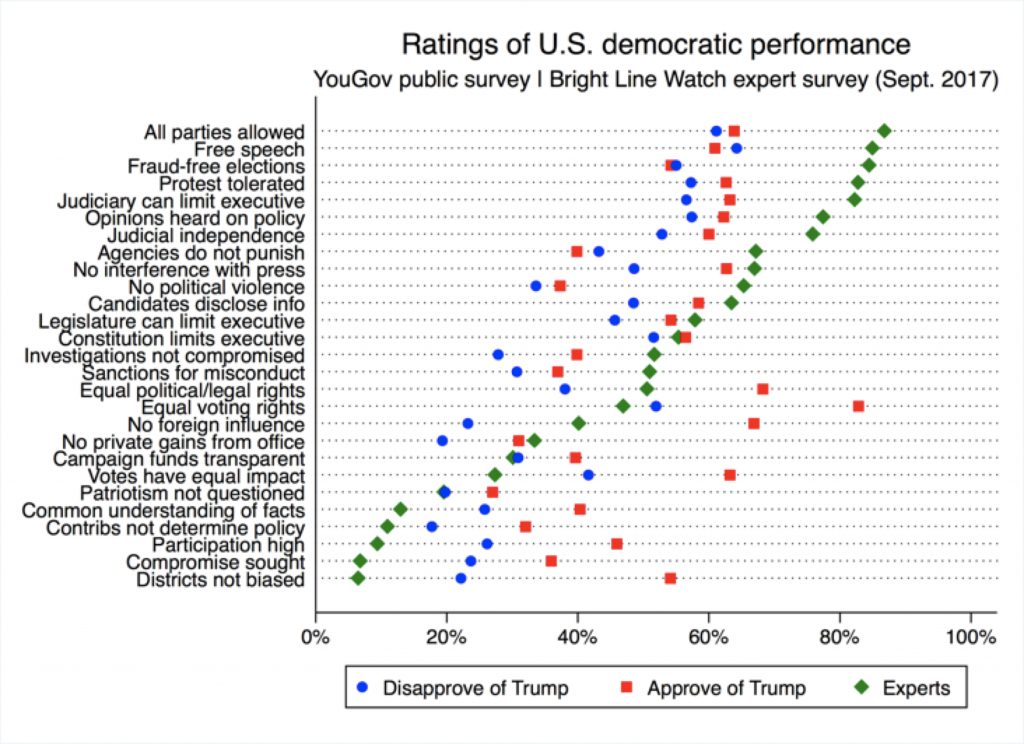

Trump supporters rate U.S. democratic performance higher than opponents

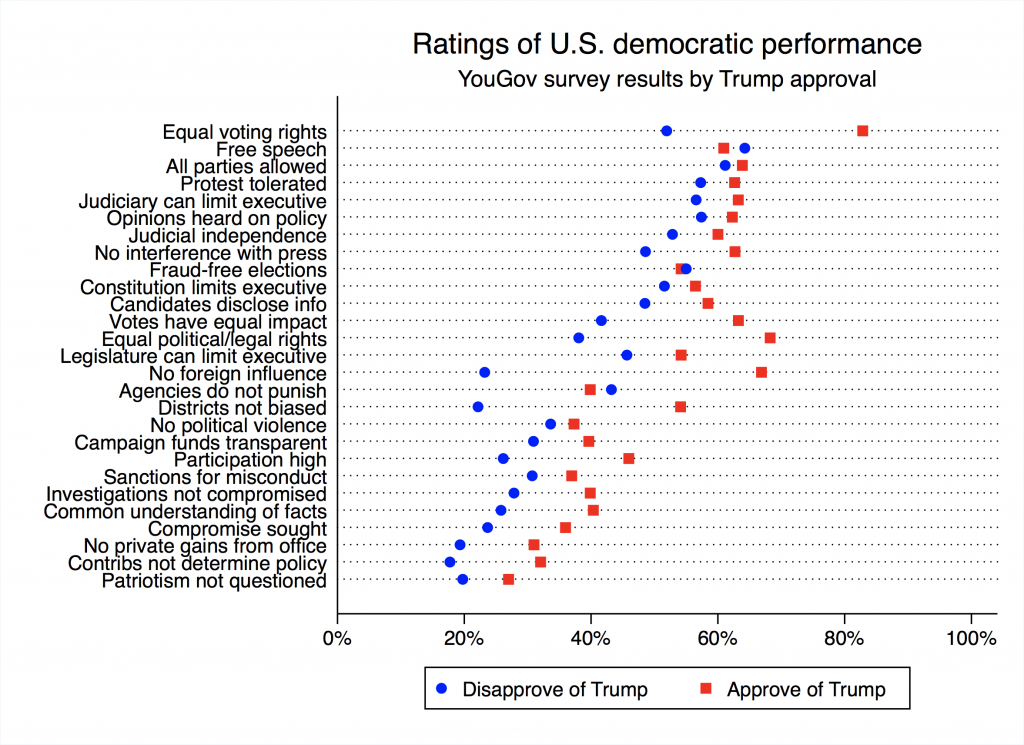

Unsurprisingly, we observe much greater polarization in views of the performance of U.S. democracy between Trump supporters and opponents. Specifically, respondents who approve of Trump rate current performance more favorably than do those who disapprove on most of our 27 principles (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

We cannot imagine anyone who would greet this news with surprise, but we direct attention to the handful of exceptions and to the wide variation in assessment gaps across items.

On four items, Trump opponents rated U.S. performance as slightly better than his supporters did: fraud-free elections, the political neutrality of government agencies, protection of free speech, and the prevention of private political violence. Trump’s supporters’ relative skepticism on the first three items likely reflects the president’s own narrative of victimhood with respect to voter fraud, politically motivated investigations, and even political correctness. The finding on private political violence is more puzzling, however, especially given that our surveys were only conducted about a month after a protester was killed in Charlottesville, VA.

We observe the greatest polarization among our respondents on whether the legal and electoral playing field is level. Trump approvers rate our democracy as dramatically better than those who disapprove at guaranteeing equal legal, political, and voting rights and at conducting elections in which all votes have equal impact, district boundaries are not biased by political partisanship, and foreign influence is limited. This list covers political reform issues on which Democrats perceive the greatest unfairness in American elections: ballot access, partisan gerrymandering, the Electoral College, and allegations of Russian influence. The broader category of equal legal rights also includes divisive issues of policing and treatment in criminal justice. In short, across principles that address the individual rights of citizens and basic fairness, those who approve of Trump and those who disapprove differ dramatically on how U.S. democracy is performing.

We see less polarization, in contrast, on items related to institutions rather than individuals. These include non-interference with the press, tolerating political parties regardless of their ideologies, providing elections that are free of outright fraud, and the effectiveness of the Constitution in limiting executive authority.

The basic message, then, is that Trump approvers and disapprovers are much farther apart in their assessments of democratic performance than on their underlying democratic priorities.

Experts: Higher importance and more variation in democratic performance

The experts we surveyed tended to regard the items on our list as more critical to democracy than members of the public regardless of their political views. This trend is visible in Figure 5 (below), which ranks statements in descending order of their importance as rated by our expert respondents. The items with the biggest gaps between experts and the public include a number of those for which Trump supporters and opponents were relatively polarized, including press freedom and the effectiveness of legislative and judicial checks on the executive.

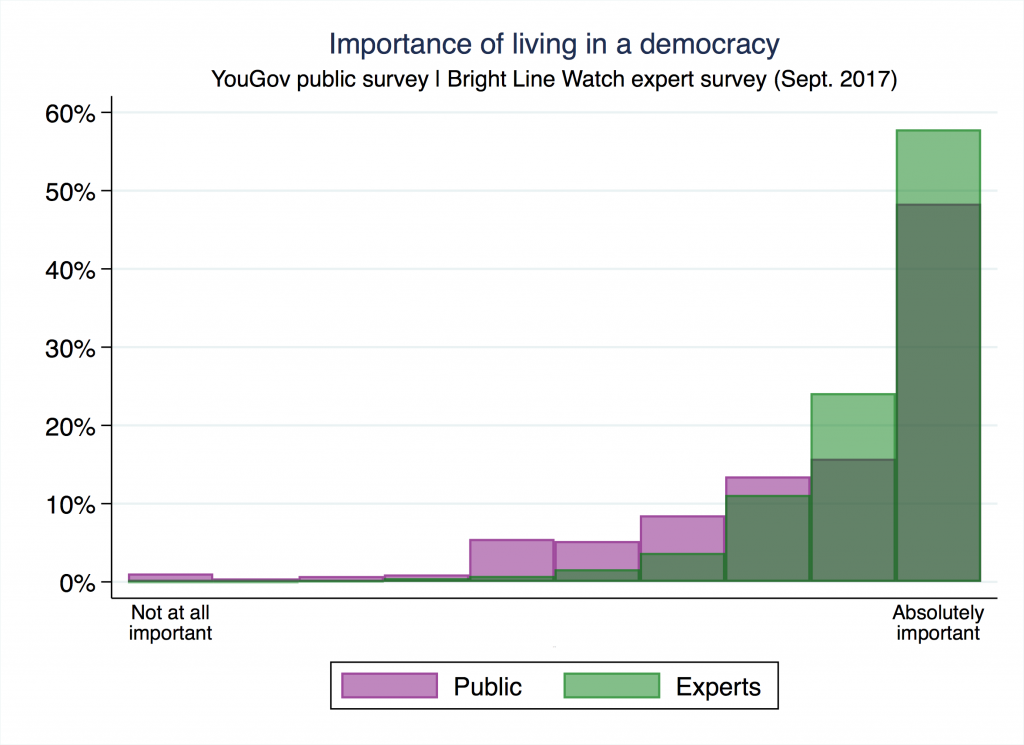

Not only did experts view discrete items as more crucial to democratic governance, they also valued living in democracy more highly. Figure 6 summarizes the difference between experts and the public in their ratings of the importance of living in a democracy. We speculate that experts’ greater awareness of authoritarian and autocratic experiences across the globe both today and in the past makes them warier of shifts away from democratic rule.

Figure 6

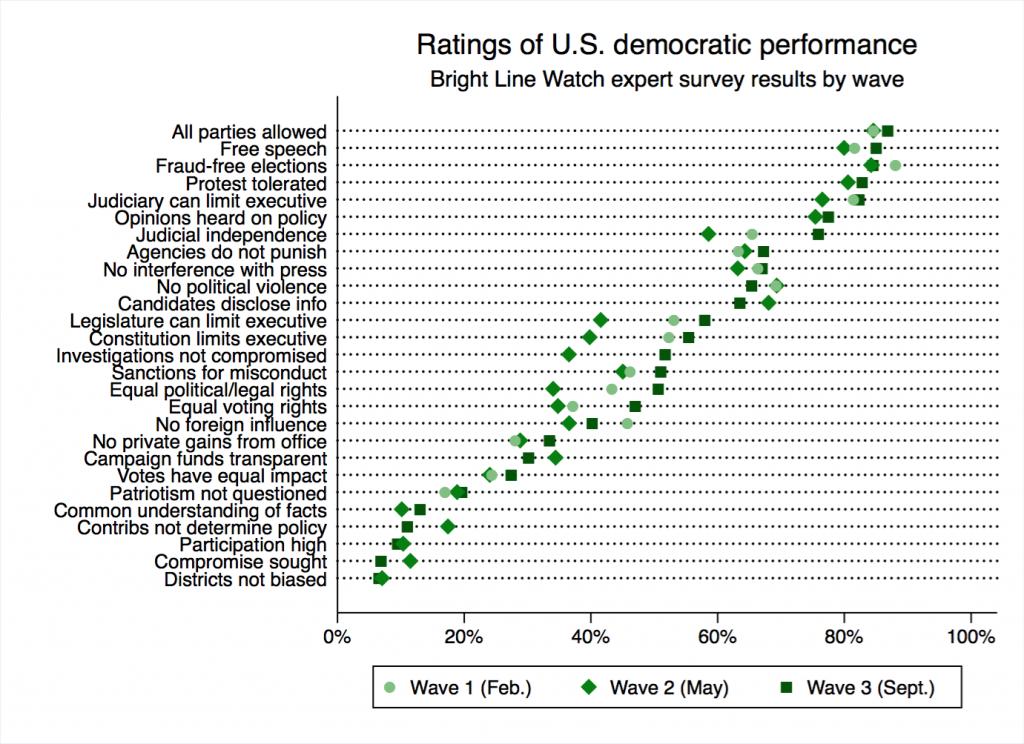

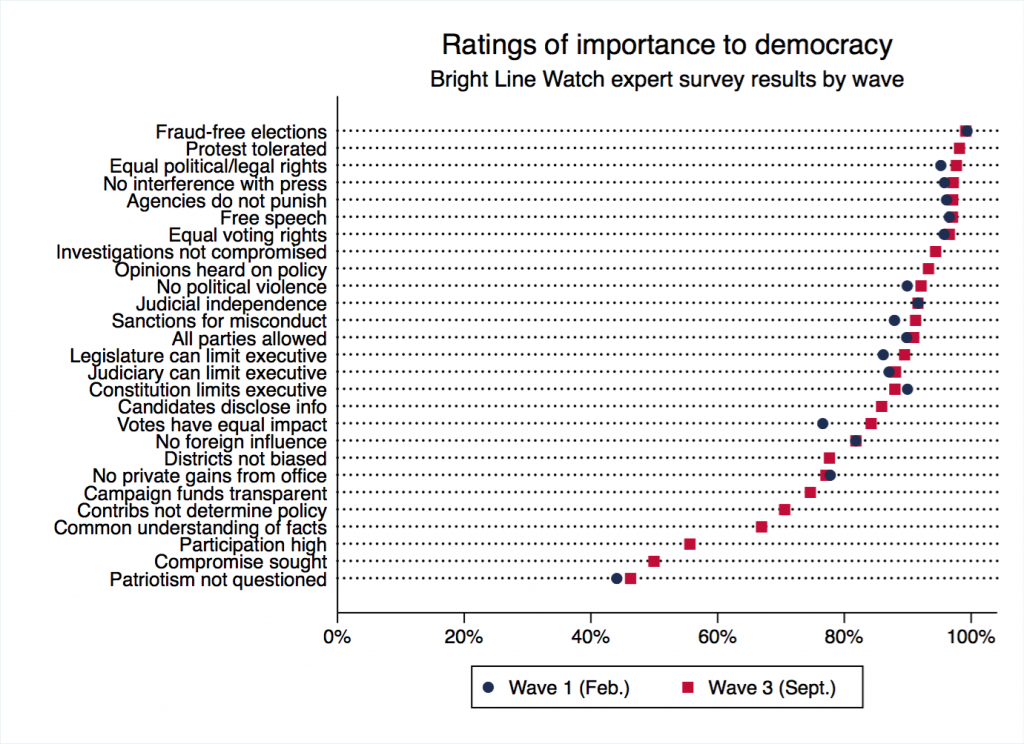

Experts do not see further erosion during the first 9 months of Trump’s presidency

To this point, we have analyzed data from our September 2017 surveys of experts and the public, but Bright Line Watch also surveyed experts in February and May 2017. As Figure 7 indicates, their assessments of U.S. democratic performance show a remarkable level of stability over time.

Figure 7

(The February survey included both importance and performance batteries; the May survey included only performance. We summarize the stability of importance ratings in Figure A5 below.)

Expert opinion is neither partisan nor alarmist

How valid are the expert ratings we collect? A common criticism of Bright Line Watch has been that political scientists are not like the public so measuring their beliefs may tell us little of relevance to politics. A more pointed version of this general critique holds that academics are reflexively hostile to President Trump and our experts are using the survey to disparage the president. However, the results from our companion expert and public surveys are inconsistent with this argument. Figure 8 compares expert versus public assessments of democratic performance on our 27 statements, with public responses again separated by respondent approval of President Trump’s job performance.

Figure 8

The most striking pattern in the figure is that the experts rate democratic performance higher than both Trump approvers and disapprovers on 15 of the 27 statements. The experts are also lower than both groups on nine statements. The former list includes a cluster of rights- and protections-related principles as well as judicial independence and the absence of outright electoral fraud. Where they are discouraged, by contrast, the experts’ dismay is also pronounced. They rank performance on electoral fairness and on civil discourse lower than even Trump opponents in the public.

On both importance and performance, the expert judgments vary more widely across statements than do those of the public. If (as we hope) our experts are unusually well informed about political issues, this finding suggests that more information leads them to draw sharper distinctions than respondents in the public sample. The surveys also show that expert judgments do not line up predictably along a Trump versus anti-Trump axis. If our expert respondents were reflexively anti-Trump and were using the surveys to hype alarmism, then we should observe experts to rate the current quality of U.S. democracy lower than the public does. The opposite is true, however, for their overall ratings and for most statements of democratic principles.

Conclusion

Bright Line Watch’s most recent surveys produced some expected results but also many we did not anticipate. We show that Trump supporters rate the current performance of U.S. democracy higher than the president’s opponents, which comes as no surprise. However, the specific areas on which Trump supporters and opponents most widely differ are instructive. We observe the greatest polarization on issues of basic fairness in electoral competition and on individual rights. On these matters, Trump approvers regard American democracy as functioning well, with solid majorities holding that democratic standards are fully or mostly met, while those who disapprove of Trump hold much more negative views. By contrast, differences between Trump supporters and opponents are less pronounced on the performance of institutions essential to democracy such as the press, political parties, and constitutional and judicial checks on authority.

The bigger surprises came in comparisons between political science experts and the public. Elite public opinion, and academia in particular, is sometimes dismissed as apocalyptic with respect to Trump and quick to declare his presidency an existential threat to American democracy. Our experts are certainly uneasy about the performance of U.S. democracy on a host of dimensions. They are particularly discouraged about norms of civility and the state of political discourse and they share much of the public’s distress about the fairness of many U.S. electoral practices. Yet expert opinion is less concerned than the public about the state of American democracy as a whole and on many of the particulars. The experts’ relative optimism might stem from their broader, more comparative perspective or from exposure to wider ranges of news sources, but either way they are less despairing than the public overall. The experts also do not perceive systematic democratic degradation in the seven months since our first survey. In short, the experts on which Bright Line Watch has depended appear to be neither alarmist nor particularly partisan in their judgments. On the whole, we regard their assessments as judicious and reassuring for our ability to learn from expert opinion going forward.

Appendix: Survey method, data, and instrument reliability

Bright Line Watch Expert survey on the state of America’s democracy, September 2017

From September 9–18, 2017, Bright Line Watch conducted its third survey on the state of democracy in the United States. Waves 1 (February 2017) and 2 (May 2017) targeted expert respondents only. In each case, we contacted nearly 10,000 political scientists who are faculty at U.S. universities, presenting respondents with a series of questions about democratic priorities and about the performance of democracy in the United States.

Wave 3 included simultaneous surveys of experts and a representative sample of the U.S. public:

- Expert: On September 10, we sent email invitations to 9,450 political science faculty, inviting participation. By September 18, after two reminder emails, we had complete responses from 1,055 (a response rate of 11%).

- Public: YouGov fielded the public survey from September 9–18, producing 3,000 complete responses.

Participants in each survey responded to identical batteries of questions about democratic priorities and performance. The data from both the expert and public surveys are available here. All analyses of the public data from YouGov incorporate survey weights.

The foundation of Bright Line Watch’s surveys is a list of 27 statements expressing a range of democratic principles. Democracy is a multidimensional concept. Our goal is to provide a detailed set of measures of democratic values and of the quality of American democracy. We are also interested in the resilience of democracy and the nature of potential threats it faces. Based on the experiences of other countries that have experienced democratic setbacks, we recognize that democratic erosion is not necessarily an across-the-board phenomenon. Some facets of democracy may be undermined first while others remain intact, at least initially. The range of principles that we measure allows us to focus attention on variation in specific institutions and practices that, in combination, shape the overall performance of our democracy.

Bright Line Watch’s Wave 1 survey included 19 statements of democratic principles. Based on feedback from respondents and consultation with colleagues, we expanded that list to 29 statements in Wave 2. We then reduced that set to what we intend to be a stable set of 27 statements for the Wave 3 surveys. 17 of those 27 statements were included in Wave 1, and all 27 were included in Wave 2.

The full set of statements is below. In the interest of clarity, this list groups the principles thematically. In the surveys, the principles were not categorized or labeled. Each respondent was shown a randomly selected subset of statements (12 for experts, 9 for the general public) and asked to first rate the importance of those statements and then rate the performance of the United States on those dimensions.

27 statements of democratic principles

Elections

- Elections are conducted, ballots counted, and winners determined without pervasive fraud or manipulation

- Citizens have access to information about candidates that is relevant to how they would govern

- The geographic boundaries of electoral districts do not systematically advantage any particular political party

- Information about the sources of campaign funding is available to the public

- Public policy is not determined by large campaign contributions

- Elections are free from foreign influence

Voting

- All adult citizens have equal opportunity to vote

- All votes have equal impact on election outcomes

- Voter participation in elections is generally high

Rights

- All adult citizens enjoy the same legal and political rights

- Parties and candidates are not barred due to their political beliefs and ideologies

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in unpopular speech or expression

- Government protects individuals’ right to engage in peaceful protest

- Citizens can make their opinions heard in open debate about policies that are under consideration

Protections

- Government does not interfere with journalists or news organizations

- Government effectively prevents private actors from engaging in politically-motivated violence or intimidation

- Government agencies are not used to monitor, attack, or punish political opponents

Accountability

- Government officials are legally sanctioned for misconduct

- Government officials do not use public office for private gain

- Law enforcement investigations of public officials or their associates are free from political influence or interference

Institutions

- Executive authority cannot be expanded beyond constitutional limits

- The legislature is able to effectively limit executive power

- The judiciary is able to effectively limit executive power

- The elected branches respect judicial independence

Discourse

- Even when there are disagreements about ideology or policy, political leaders generally share a common understanding of relevant facts

- Elected officials seek compromise with political opponents

- Political competition occurs without criticism of opponents’ loyalty or patriotism

At the core of the surveys were two batteries of questions based on these statements of principle. In the first battery, participants were asked, “How important are these characteristics for democratic government?” Each respondent was presented a subset of randomly selected statements (12 for experts, 9 for the general public) to rate on the following scale:

- Not relevant. This has no impact on democracy.

- This enhances democracy, but is not required for democracy.

- If this is absent, democracy is compromised.

- A country cannot be considered democratic without this.

The second battery asked, “How well do the following statements describe the United States as of today?” Each respondent was then presented with the same statements they evaluated for importance, using the following response options:

- The U.S. does not meet this standard.

- The U.S. partly meets this standard.

- The U.S. mostly meets this standard.

- The U.S. fully meets this standard.

- Not sure.

The order in which statements were presented in each battery was randomized for each respondent so there should be no priming or ordering effects in how they were assessed.

After completing these batteries on importance and U.S. performance, we asked respondents to rate the overall quality of democracy in the United States today on a scale from 1 to 100, where 1 is least democratic and 100 is most democratic. We then asked, “How important is it for you to live in a country that is governed democratically?” on a 1–10 scale where 1 means it is “not at all important” and 10 means “absolutely important.”

Illustrations of additional results

The figures that follow offer a more granular view of responses to our surveys. In Figures A1 to A4, the statements are presented in descending order of positive responses. For importance ratings, we tallied the proportion of responses that assessed a given principle as “essential” or “important” to democracy (rather than merely “beneficial … but not required” or “not relevant”). On performance, we tallied the proportion that assessed the United States as “fully” or “mostly” meeting the standard (rather than “partly” or “does not meet”).[1]

Figure A1: Importance to democracy — experts

Figure A2: Importance to democracy — public

Figure A3: U.S. democracy performance — experts

Figure A4: U.S. democracy performance — public

The Bright Line Watch survey instrument is reliable

Our last main point is a methodological one but nonetheless critically important. The Wave 3 survey provided us an opportunity to test the reliability of our survey instrument by comparing expert responses on the importance of democratic principles to Wave 1. We expect these perceptions to be stable among our respondents (unlike ratings of democratic performance, which may vary over time). For that reason, we did not include the importance battery on the Wave 2 survey and do not intend to repeat it in every wave, as with performance. However, we did repeat the importance battery on Wave 3 to allow us to compare expert and public ratings of democratic performance at the same time. These ratings provide us with the opportunity to compare expert responses on importance between February and September 2017. The results are shown in Figure A5.

Figure A5

On the 17 statements included in both waves, the importance ratings are strikingly consistent. These results suggests that the instrument is highly reliable.

[1] Responses of “not sure” are excluded when calculating those proportions.